- Home

- Jack Kerouac

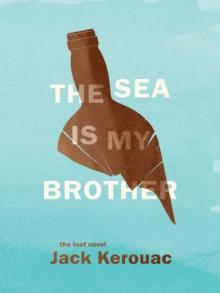

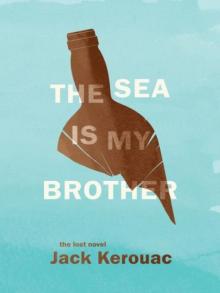

The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel

The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Introduction

CHAPTER ONE - The Broken Bottle

CHAPTER TWO - New Morning

CHAPTER THREE - We Are Brothers, Laughing

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

Copyright Page

Introduction

The first major work by Jack Kerouac, The Sea Is My Brother was written in the spring of 1943 and until now has never been published in its entirety. The novel offers the reader a glimpse of a Jack who is at odds with his own youthful idealism and the harsh realities of a nation at war. His character studies reveal much of what we expect from Jack’s observational style providing many glimpses into his early writing experiments while presenting us with an introspective view of Jack as a young man played out in the two main characters. Everhart who is encouraged by his new friend, the reckless and high-spirited Martin, to hitchhike to Boston and sign up as a Merchant Marine, finds himself taking risks that he never would have considered before meeting Martin. This contradiction, embodied in the two main characters, Bill Everhart and Wesley Martin, is exemplified in their first meeting: “Everhart studied the stranger; once, when Wesley glanced at Everhart and found him ogling from behind the fantastic spectacles, their eyes locked in combat, Wesley’s cool and non-committal, Everhart’s a searching challenge, the look of the brazen skeptic.”

Jack began several stories based on his adventures at sea with different titles and characters. He did make a few starts on the first chapter of this story as well which contains some enlightening notes by Jack concerning the development of the novel’s characters around what he felt was his own dual personality.

Soon, I knew I was too old to persist in my boyhood ways. Reluctantly, I gave it up. (Someday, I’ll explain to you the details of this world—they are enormous in number and complex to a point of maturity.)

Thus on the one side, the solitary boy brooding over his “rich inner life”; and on the other, the neighborhood champ shooting pool down at the club. I’m convinced I shouldn’t have picked up both these personalities had I not been an immense success in the two divergent personality-worlds. It is a rare enough occurrence . . . and none of the Prometheans1 seem to have these two temperaments, save, perhaps, [George] Constantinides.

Naturally enough, my worldly side will wink at the wenches, blow foam off a tankard, and fight at the drop of a chip. My schzoid self, on another occasion, will sneer, slink away, and brood in some dark place.

I’ve gone to all this trouble, outlining my dual personality, for a purpose besides egocentricity. In my novel, you see, Everhart is my schzoid self, Martin the other; the two combined run the parallel gamut of my experience. And in both cases, the schzoid will recommend Prometheanisms (if I may coin the phrase), and the other self (Wesley Martin) will act as the agent of stimulus—And as in all my other works, “The Sea Is My Brother” will Assert the presence of beauty in life, beauty, drama, and meaning. . . .

The majority of Everhart’s character is derived from Jack’s own experiences. Everhart’s intellectual pursuits, for example, can be achieved with very little risk, for he lives with his father, brother, and sister much like Jack. Everhart’s desire to experience something more real and stimulating, echoes Jack’s recent rebellious voyage on the Dorchester and his dropping out of Columbia. Therefore Everhart’s decision to take a leap-of-faith symbolizes in many ways Jack’s desire to turn away momentarily from his intellectual self and use his perceptive nature to inspire his work. Jack noted this need for real experiences in his journal: “My mother is very worried over my having joined the Merchant Marine, but I need money for college, I need adventure, of a sort (the real adventure of rotting wharves and seagulls, winey waters and ships, ports, cities, and faces & voices); and I want to study more of the earth, not out of books, but from direct experience” (July 20, 1942).

The character Martin on the other hand is free of any intellectual burdens; this is Jack’s “worldly side,” is free to come and go with no strings attached. A wanderer of the world, Martin goes from port to port taking in the experiences without fear or commitment. In a letter to Jack’s friend Sebastian Sampas in November 1942, he tries to convince him to ship out with him in the Merchant Marines: “But I believe that I want to go back to sea . . . for the money, for the leisure and study, for the heart-rending romance, and for the pith of the moment.” Jack’s notes on another working copy of the novel reinforce his intention to include every aspect of his worldly experience: “Into this book, ‘The Sea Is My Brother’, I shall weave all the passion and glory of living, its restlessness and peace, its fever and ennui, its mornings, noons and nights of desire, frustration, fear, triumph, and death. . . .”

In the same letter to Sebastian Jack laid out the internal soul-searching dilemma that The Sea Is My Brother is attempting to resolve:

I am wasting my money and my health here at Columbia . . . it’s been one huge debauchery. I hear of American and Russian victories, and I insist on celebrating. In other words, I am more interested in the pith of our great times than in dissecting “Romeo and Juliet” . . . . at the present, understand. . . . Don’t you want to travel to the Mediterranean ports, perhaps Algiers, to Morocco, Fez, the Persian Gulf, Calcutta, Alexandria, perhaps the old ports of Spain; and Belfast, Glasgow, Manchester, Sidney, New Zealand; and Rio and Trinidad and Barbados and the Cape; and Panama and Honolulu and the far-flung Polynesians . . . I don’t want to go alone this time. I want my friend with me . . . my mad poet brother.

The references about wasting money at Columbia parallel Everhart’s internal questioning “What was he doing with his life?” and become his impetus for shipping out with Martin. Amongst Jack and his friends from Lowell there was much correspondence during this time. They wrote of comrades and brotherhood, topics which are an integral part of this novel and help to resolve Jack’s battle with his changing political views. When he was younger his infatuation with the idealism expressed in the letters to his friends and the ongoing dialogs in the media regarding the various political movements give way to his more critical nature which began to develop after his induction into the Navy. He wrote to Sebastian on March 25,1943 from the Navy barracks: “Though I am skeptical about the administration of the Progressive movement, I shall withhold all judgments until I come in direct contact with these people—other Communists, Russians, politicians, etc., leftists artists, leaders, workers, and so forth.”

The Sea Is My Brother is a seminal work marking Jack’s transition as a writer and represents the earliest evidence of the development of his style. He tells Sebastian in a letter, dated March 15, 1943; “I am writing 14 hours a day, 7 days a week . . . I know you’ll like it, Sam; it has compassion, it has a certain something that will appeal to you (brotherhood, perhaps).”

Shortly after he wrote The Sea Is My Brother, Jack began The Town and the City, published in 1950, which launched his career as a writer. These two novels, both based on his real-life experiences, are part of the writing method he started to develop in 1943 that he dubbed “Supreme Reality.”

Jack began this work not long after his first tour as a Merchant Marine on the S.S. Dorchester from the late summer—October of 1942 during which he kept a journal detailing the gritty daily routine of life at sea. The journal titled “Voyage to Greenland” is dated 1942 and subtitled “GROWING PAINS or A MONUMENT TO ADOLESCENCE”. Inspired by the trip, the journal is an example of Jack’s love for adventure, the character traits of his fellow shipmates which created spontaneous sketches of those experiences that were late

r woven into this novel.

Jack often revisited his journals adding notes and did so here with a poem dated April 17, 1949 several years after the Sea Is My Brother was written.

All life is but a skull-bone and

A rack of ribs through which

we keep passing food & fuel—

just so’s we can burn so

furious beautiful.

The first entry dated Saturday July 18, 1942 describes his first night on deck the Dorchester, the meal he ate (five lamb chops), and this passage written early the next morning: “I sat in a deck chair, awhile after and bethought me about several things. How should I write this journal? Where is this ship bound for, and when? What is the destiny of this great grey tub? I signed on Friday, or yesterday, and do not begin work till Monday morning. . . . I could have gone home to say goodbye—but goodbyes are so difficult, so heart-rending. I haven’t the courage, or perhaps the hardness, to withstand the tremendous pathos of this life. I love life’s casual beauty—fear its awful strength.”

Early on in the “Voyage to Greenland” journal is evidence of his plans for the observations he was making: “Up to now, I’ve refrained from introducing any characters in this journal, for fear I should be mistaken due to a brief acquaintance with those in question, and should be forced to rescind previous opinions and judgments.” Jack continues that although it would create an “acceptable log,” that he felt it should “tell the story within the story,” and that since he shall “perhaps one day want to write a novel about the voyage,” and he would be able to find all the details on file: “a true writer never forgets character studies, and never will.” Later the same day he began these character studies.

August 2

CHARACTER STUDIES

Here is some data on my scullion mates, and others: Eatherton is just a good-hearted kid from the “tough” section of Charleston, Mass, who tries to live up to his environment, but fails, for his smile is too boyish, too puckish. He is a veteran seaman already, and berates me for being a despicable “college man” who “reads books all the time and knows nothing about life itself.” Don Graves is an older boy, quite handsome, with a remarkable sense of wit and tomfoolery that often befuddles me. He is able to toy with people’s emotions, for he undeniably possesses a strong, moving personality. He’s 27 years old, and I believe he looks upon me with some mixed pity and head-shaking—but no compassion. He has little of that, and no learning; but considerable earthy judgment and native ability, and a sort of appeal that is quiet and sure. Eddie Moutrie is a cussing little bastard, full of venom and dark, haggard beauty, often tenderness. I envision him now, smoking with his contemptuous scowl, turned away, yelling derision at me in a rough, harsh voice, returning his gaze with blank and tender eyes.

August 2

MORE

They are good kids, but cannot understand me, and are thus enraged, bitter, and full of hidden wonder. Then there is the chef, a fat colored man with prominent but-toxes [sic] who loves to play democratic and often peels potatoes with us. His face is fat and sinuous, touched with childish propriety. His face seems to say: “Now, we are here, and things are in all due harmony and order.” He has grown fat on his own foods. He sits at our mess table, wearing a fantastic cook’s cap, and picks delicately with fat greasy hands at his food. All things are in order with the chef. He is the antithesis of Voltaire, the child of Leibniz.

Then there’s Glory, the giant negro cook, whose deep voice can always be heard in its moaning softness above the din of the galley. He is a man among men—gentle, impenetrable, yet a leader. The glory that is Glory . . .

“Shorty” is a withered, skinny little man without teeth and a little witch jaw. He weighs about 90 pounds, and when he’s mad, he threatens to throw us all through the portholes.

“Hazy” is a powerfully built, ruddy

August 2

LES MISERABLES

Youth who works, eats, and sleeps, and rarely speaks. He’s always in his bunk, sleeping, smiling when Eatherton farts toward his face: then turns over back to his solitary, sleepy world.

“Duke” Ford is a haggard youth who has been torpedoed off Cape Hatteras, and who carries the shrapnel marks of the blast in his neck. He is a congenial sort but the frenzied mark of tragedy still lingers in his eyes; and I doubt whether he’ll ever forget the 72 hours on the life raft, and the fellow with bloody stumps at his shoulders who jumped off the raft in a fit of madness and committed suicide in the Carolinian sea . . .

Then there’s the rather stupid Paul, an awkward, almost idiotic youth, the butt of all the leg-pullers in the crew. They are making a mess of the tenderness his mother must have taught him. His voice is a strange mixture of kindness, despair, and futile attempts at snarling pseudo-virility. It is pathetic to see this poor lad in the midst of callous fools and stupid bums . . . for most of the crew is just that, and I shall not write of them except

August 2

VAL, THE LADIES’ CHOICE

as a man body in this narrative. They have no manners, no scruples, and spend their leisure time gambling in the dining room, their dull countenances glowing with ancient cruelty under the golden lights. O Satan! Mephisto! Judas! O Benaiah! O evil eyes that glint beneath the lights! O clink of silver! O darkness, O death, O hell! Sheathed knives and chained wallets: lustful, grabbing, cheating, killing, hating, laughing in the lights . . .

Jack’s journal ends on August 19, 1942 shortly after reaching Greenland. The last entries are a short story entitled “‘WHAT PRICE SEDUCTION?’ OR A 5 CENT ROMANCE IN ONE REEL A SHORT SHORT STORY—‘THE COMMUNIST,’” two poems, a descriptive character piece called “PAT,” and a set of notes called JACK KEROUAC FREE VERSE, FOUR PARTS.2

This next poem encompasses many of the daily frustrations expressed in the journal about being different than the rest of the crew.

WHEN I WAS OUT TO SEA

Once, when I was out to sea,

I knew a lad who’s famous now.

His name is sung in America,

And carried far to other lands.

But when I knew him, far back now,

He was a lad with lonely eyes.

The bos’un laughed when Laddie wrote:

“Truth Brothers!” in his diary.

“You daggone little pansy!”

Roared the heavyset rough bos’un.

“You don’t know what life be,

You with all your sissy books!

Look at me! I’m rough and I’m tough,

And I got lots to teach ye!”

So the bos’un jeered, and the bos’un snarled,

And he set him down to drudgery.

And the boy, he and his poetry,

He wanted to stand bow-watch

And brood into the sea,

But the bos’un laughed, and snarled,

And set him down to drudgery.

Down in the hold, mid fetidity . . .

Then one night, a wild dark night,

The lad stood by the heaving bow

And the storm beat all about him.

The bos’un he laughed and set right out

To put him down to drudgery,

That sissy lad of poetry . . .

With wind and sky all scattered wide,

A grim, dreary night for fratricide!

–JK

Jack disembarked the Dorchester but continued to think of the sea as a symbol for the integration of his friends and the promise of brotherhood. After a brief return to Columbia University he moved back to Lowell with his parents and got a job at a garage on Middlesex Street where he works diligently night and day writing by hand his first novel. The novel’s importance to this early period of Jack’s life is indisputable. Although a short novel, it represents a pivotal point in his writing career where his serious intention to become a writer resonates in the power of his speech and the depth of his visualization.

The placement of hyphens, dashes, ellipses, apostrophes, etcetera, have all been maintaine

d only standardized for readability. In cases of spelling errors, I have corrected unless thought to be intentional and have included some editorial elements and or additional punctuation when needed which can be found in brackets [. . .] and in cases were material is missing, illegible or otherwise obscured, I have shown this with empty brackets [ ]. In places where Jack Kerouac has edited his own material by crossing out and re-writing; I have only included that which he preserved unless context is unclear or words appear to be missing. Spacing and line breaks have been preserved in some cases where the emphasis of the words would be affected, otherwise the margins, indents and line spacing have been standardized. Kerouac’s entire archive can be found in the Berg Collection of the New York Public Library.

CHAPTER ONE

The Broken Bottle

A young man, cigarette in mouth and hands in trousers’ pockets, descended a short flight of brick steps leading to the foyer of an uptown Broadway hotel and turned in the direction of Riverside Drive, sauntering in a curious, slow shuffle.

It was dusk. The warm July streets, veiled in a mist of sultriness which obscured the sharp outlines of Broadway, swarmed with a pageant of strollers, colorful fruit stands, buses, taxis, shiny automobiles, Kosher shops, movie marquees, and all the innumerable phenomena that make up the brilliant carnival spirit of a midsummer thoroughfare in New York City.

The young man, clad casually in a white shirt without tie, a worn gabardine green coat, black trousers, and moccasin shoes, paused in front of a fruit stand and made a survey of the wares. In his thin hand he beheld what was left of his money—two quarters, a dime, and a nickel. He purchased an apple and moved along, munching meditatively. He had spent it all in two weeks; when would he ever learn to be more prudent! Eight hundred dollars in fifteen days—how? where? and why?

When he threw the apple core away, he still felt the need to satisfy his senses with some [ ] dawdle or other, so he entered a cigar store and bought himself a cigar. He did not light it until he had seated himself on a bench on the Drive facing the Hudson River.

Tristessa

Tristessa On the Road

On the Road The Dharma Bums

The Dharma Bums Maggie Cassidy

Maggie Cassidy Big Sur

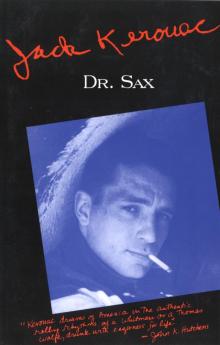

Big Sur Dr. Sax

Dr. Sax Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46

Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46 The Sea Is My Brother

The Sea Is My Brother The Town and the City: A Novel

The Town and the City: A Novel Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Desolation Angels: A Novel

Desolation Angels: A Novel Book of Sketches

Book of Sketches Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha

Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha The Electrocution of Block 38383939383

The Electrocution of Block 38383939383 Haunted Life

Haunted Life Visions of Gerard

Visions of Gerard Orpheus Emerged

Orpheus Emerged Book of Blues

Book of Blues The Subterraneans

The Subterraneans The Haunted Life

The Haunted Life The Unknown Kerouac

The Unknown Kerouac The Town and the City

The Town and the City Visions of Cody

Visions of Cody Atop an Underwood

Atop an Underwood Lonesome Traveler

Lonesome Traveler Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg Vanity of Duluoz

Vanity of Duluoz Desolation Angels

Desolation Angels On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition)

On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition) The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel

The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel Wake Up

Wake Up The Poetry of Jack Kerouac

The Poetry of Jack Kerouac Doctor Sax

Doctor Sax