- Home

- Jack Kerouac

The Town and the City

The Town and the City Read online

EARLY BIRD BOOKS

FRESH EBOOK DEALS, DELIVERED DAILY

LOVE TO READ?

LOVE GREAT SALES?

GET FANTASTIC DEALS ON BESTSELLING EBOOKS

DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX EVERY DAY!

The Town and the City

A Novel

Jack Kerouac

BOOKS BY JACK KEROUAC

The Town and the City

1950

On the Road

1957

The Dharma Bums

1958

The Subterraneans

1958

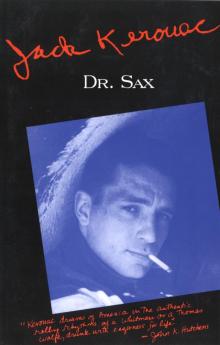

Doctor Sax

1959

Maggie Cassidy

1959

Mexico City Blues

1959

Excerpts from Visions of Cody

1960

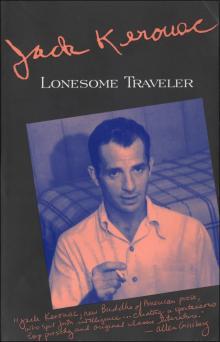

Lonesome Traveler

1960

The Scripture of the Golden Eternity

1960

Book of Dreams

1961

Big Sur

1962

Visions of Gerard

1963

Desolation Angels

1965

Satori in Paris

1966

Vanity of Duluoz: The Adventurous

Education of a Young Man

1968

to R. G.

Friend and Editor

1

[1]

The town is Galloway. The Merrimac River, broad and placid, flows down to it from the New Hampshire hills, broken at the falls to make frothy havoc on the rocks, foaming on over ancient stone towards a place where the river suddenly swings about in a wide and peaceful basin, moving on now around the flank of the town, on to places known as Lawrence and Haverhill, through a wooded valley, and on to the sea at Plum Island, where the river enters an infinity of waters and is gone. Somewhere far north of Galloway, in headwaters close to Canada, the river is continually fed and made to brim out of endless sources and unfathomable springs.

The little children of Galloway sit on the banks of the Merrimac and consider these facts and mysteries. In the wild echoing misty March night, little Mickey Martin kneels at his bedroom window and listens to the river’s rush, the distant barking of dogs, the soughing thunder of the falls, and he ponders the wellsprings and sources of his own mysterious life.

The grownups of Galloway are less concerned with riverside broodings. They work—in factories, in shops and stores and offices, and on the farms all around. The textile factories built in brick, primly towered, solid, are ranged along the river and the canals, and all night the industries hum and shuttle. This is Galloway, milltown in the middle of fields and forests.

If at night a man goes out to the woods surrounding Galloway, and stands on a hill, he can see it all there before him in broad panorama: the river coursing slowly in an arc, the mills with their long rows of windows all a-glow, the factory stacks rising higher than the church steeples. But he knows that this is not the true Galloway. Something in the invisible brooding landscape surrounding the town, something in the bright stars nodding close to a hillside where the old cemetery sleeps, something in the soft swishing treeleaves over the fields and stone walls tells him a different story.

He looks at the names in the old cemetery: “Williams … Thompson … LaPlanche … Smith … McCarthy … Tsotakos.” He feels the slow deep pulsing of the river of life. A dog barks on the farm a mile away, the wind whispers over the old stones and in the trees. Here is the recorded inscription of long slow living and long-remembered death. John L. McCarthy, remembered as a man with white hair who walked down the road in meditation at dusk; old Tsotakos, who lived and worked and died, whose sons continue to work the land not far from the cemetery; Robert Thompson—bend near and read the dates, “Born 1901, died 1905”—the child who drowned three decades ago in the river; Harry W. Williams, the storekeeper’s son who died in the Great War in 1918 whose old sweetheart, now the mother of eight children, is still haunted by his long lost face; Tony LaPlanche, who molders by the old wall. There are old people, living and still remembering, who could tell you so much about the dead of Galloway.

As for the living, walk down the hillside towards the quiet streets and houses of Galloway’s suburbs—you will hear the river’s ever-soughing rush—and pass beneath the leafy trees, the streetlamps, along the grass yards and dark porches, the wooden fences. Somewhere at the end of the street there’s a light, and intersections leading to the three bridges of Galloway that bring you into the heart of the town itself and to the shadow of the mill walls. Follow along to the center of the town, the Square, where at noon everybody knows everybody else. Look around now and see the business of the town deserted in haunted midnight: the five-and-ten, the two or three department stores, the groceries and soda fountains and drugstores, the bars, the movie theaters, the auditorium, the dance hall, the poolrooms, the Chamber of Commerce building, the City Hall and the Public Library.

Wait around for the morning, for the time when the Real Estate offices come to life, when lawyers raise the windowshades and the sun floods into dusty offices. See these men standing at windows, on which their names are written in gold letters, nodding down at the street when other townsmen walk by. Wait for the busses to come around laden with working people who cough and scowl and hurry to the cafeteria for another cup of coffee. The traffic cop stations himself in the middle of the Square, nodding to a car which toots at him jovially; a wellknown politician crosses the street with the bright sun on his white hair; the local newspaper columnist comes sleepily to the cigar store and greets the clerk. Here are a few farmers in trucks buying up supplies and groceries and transacting a little business. At ten o’clock the women come in armies, with shopping bags, their children trailing alongside. The bars open, men gulp a morning beer, the bartender mops the mahogany, there’s a smell of clean soap, beer, old wood, and cigar smoke. At the railroad station the express going down to Boston puffs shooting clouds of steam around the old brown turrets of the depot building, the streetguards descend majestically to stop traffic as the bell rings and jangles, people rush for the Boston train. It’s morning and Galloway comes to life.

Out on the hillside, by the cemetery, the rosy sun slants in through the elm leaves, a fresh breeze blows through the soft grass, the stones gleam in the morning light, there’s the odor of loam and grass—and it’s a joy to know that life is life and death is death.

These are the things that closely surround the mills and the business of Galloway, that make it a town rooted in earth in the ancient pulse of life and work and death, that make its people townspeople and not city people.

Start from the center of town in the sunny afternoon, from Daley Square, and walk up River Street where all the traffic is converged, pass the bank, the Galloway High School and the Y.M.C.A., and move on up till private residences begin to appear. Leaving the business district behind, the great factory walls are barely within reach to the left and to the right of the business district. Along the river is a quiet street with a few sedate funeral homes, an orphanage, brick mansions of a sort, and the bridges that leap across to the suburbs, where most of the people of Galloway live. Cross the bridge known as the White Bridge, swooping right over the Merrimac Falls, and pause for a moment to view the prospect. Citywards there is one more bridge, the wide smooth basin where the river turns, and beyond that a faroff flank of land thickly populated. Look away from the city, over the frothing falls, and see into misty reaches that include New Hampshire, an expanse of green placid land and calm water. There are the railroad tracks running along the river, a few water tanks and sidings, but the rest is all wooded. The far side of the river presents a highway dotted with roadhouses and roadside stands, and a return gaze from

upriver reveals the suburbs thick with rooftops and trees. Cross the bridge to these suburbs, and turn upriver, along the flank of populations, along the highway, and there is a narrow black tar road leading off inland.

This is old Galloway Road. Just where it rises, before dipping once more into pine forests and farmlands, lies a concentration of houses sedately spaced off from one another—a residence of ivied stone, the house of a judge; a whitewashed old house with round wooden pillars on the porch—this is a dairy farm, there are cows in the field beyond; and one rambling Victorian house with a battered gray look, a high hedgerow all around, trees huge and leafy that almost obscure the front of the house, a hammock on the old porch, and a disheveled backyard with a garage and a barn and an old wooden swing.

This last house is the home of the Martin family.

From the top of the highest elm in the front yard, as some of the vigorous Martin kids can testify, on a good day it is possible to see clear to New Hampshire over farmlands and thick pine-woods, and on exceptionally clear days even the misty intimations of the White Mountains are visible sixty miles north.

This house had especially appealed to George Martin when he considered leasing it in 1915. He was then a young insurance salesman, living in a flat in town with his wife and one daughter.

“By God,” he had said to his wife, Marguerite, “if this isn’t just what the doctor ordered!”

Whereupon, during the next twenty years in the big rambling house, in collaboration with Mrs. Martin, he set about to produce eight more children, three daughters and six sons all told.

George Martin had gone into the printing business and made a great success of himself in the town, first as a job-printer and later as a printer-publisher of small political newspapers that were read mainly in City Hall swivel chairs or at the cigar stores. He was a scowling, preoccupied, virile-looking man, big, genial, eagerly sympathetic, who could suddenly break out into a booming raspy laugh or just as easily grow very sentimental and misty-eyed. He knitted his brow in a kind of fierce concentration over a pair of heavy black eyebrows, his eyes were level and blue, and when someone spoke to him he had a habit of looking up with a startled air of wonder.

He had come down from Lacoshua, New Hampshire, a country town in the hills, as a youth, abandoning work in the sawmills for a crack at the town.

Over the years his family gave character to the old gray house and to its grounds, rendering its shambling air of simplicity, haphazardness, and glass. It was a house that rang with noises and conversations, music, hammer-slammings, shouts down the stairs. At night almost all of its windows glowed as the innumerable activities of the family were carried on. In the garage were a new car and an old car, in the old barn was all the accumulated bric-a-brac that only an American family with many boys can assemble over the years, and in the attic the confusion and the variety of objects were nothing less than admirable.

When all the family was stilled in sleep, when the streetlamp a few paces from the house shone at night and made grotesque shadows of the trees upon the house, when the river sighed off in the darkness, when the trains hooted on their way to Montreal far upriver, when the wind swished in the soft treeleaves and something knocked and rattled on the old barn—you could stand in old Galloway Road and look at this home and know that there is nothing more haunting than a house at night when the family is asleep, something strangely tragic, something beautiful forever.

[2]

Each member of the family living in this house is wrapped in his own vision of life, and is brooding within the enveloping intelligence of his own particular soul. With the family stamp somehow imprinted upon each of their lives, they come infolded and furious into the world as Martins, a clan of energetic, vigorous, grave and absorbed people, suddenly terrified and melancholy, suddenly guffawing and gleeful, naive and cunning, meditative often and just as often ravenously excited, a strong and clannish and shrewd people.

Consider them one by one, the youngsters who are taking in impressions of the world around as though they expected to live forever, on up to the elder members of the family who find assurance everywhere and every day that life is exactly what they always supposed it to be. See how they all go through their succession of days, the robust exuberant days, the days of celebration, and the days of sickness of heart.

The Martin father is a man of a hundred absorptions: he conducts his printing business, runs a linotype and a press, and keeps the books. In the midst of this he plays the horses and places his bets with a bookie in a downtown back-street, Rooney Street. At noon he carries on a shouting conversation with insurance men, newspapermen, salesmen and cigar store proprietors in a little bar off Daley Square. On his way home to supper he stops off at the Chinese restaurant to see his old friend Wong Lee. After supper he listens to his favorite programs, sitting in his den with the radio on full-blast. After dark he drives over to the bowling-alley and poolroom which he supervises, in order to bring in a little extra money. There he sits in the little office talking with a congregation of his old friends while the billiard balls click, the alleys roll and thunder, and everywhere there’s smoke and talk. At midnight he finds himself in a big poker or pinochle game that lasts long into the night. He comes home exhausted, but in the morning he’s off again to his place of business trailing cigar smoke behind him, shouting good mornings to his associates in the shop, eating a hearty breakfast in the diner by the railroad tracks.

On Sundays he absolutely must go driving in his Plymouth, bringing with him a good portion of his family that wants to come along. He drives all over New England, exploring the White Mountains, the old towns on the coast and inland, he wants to stop off everywhere where the food or ice cream looks good, he wants to buy bushels of Mackintosh apples and jars of cider at the roadside stands, and whole baskets of strawberries and blueberries and as much corn as he can carry on the floor of the car. He wants to smoke all the cigars, get in on all the poker games, know all the roads and shores and towns in New England, eat in all the good restaurants, make friends with all the good men and women, follow all the racetracks and bet in all the bookie-backrooms, make as much money as he spends, kid around and laugh and make jokes all the time—he wants to do everything, he does everything.

The Martin mother is a superb housekeeper who according to her husband is “the best darned cook in town.” She bakes cakes, roasts great cuts of beef and lamb and pork, keeps her icebox bulging with food, sweeps the floors and washes clothes and does everything that the mother of a big family does. When she sits down to relax, there she is with her deck of cards, shuffling, peering over the rim of her spectacles and foreseeing tidings of good fortune, forebodings of doom, omens of all sorts and sizes. She sits at the kitchen table with her eldest daughter and discerns the news in the bottom of her teacup. She reads signs everywhere, follows the weather closely, reads the obituaries and notices of marriage and birth, keeps track of all illness and ill-fortune, of all bustling health and good luck, she traces the growth of children and the decline of old men all over the town, the omen-tidings of other women and the approach of new seasons. Nothing escapes the vast motherly wisdom of this woman: she has foreseen it all, sensed everything.

“You don’t have to believe it, if you don’t want to,” she says to her eldest daughter Rose, “but I had a dream the other night that my little Julian came to me at night, right into bed like he used to do when he was too sick to sleep or when he was scared of the dark, like he used to do that year he died, and he said to me ‘Mama,’ he said, ‘are you worried about Ruthey?’ and I said ‘Yes, darling, but why do you ask me?’ and he said ‘Don’t be afraid for Ruthey any more, it’s all right now, it’s all right now.’ He kept saying that: ‘It’s all right now.’ And he looked just like he was the weeks before he died, with his little brow all pale and covered with perspiration, his little sad eyes wide as though he wanted to know why it was that he had to be so sick. It was such a vivid dream! He was right there in front of me, Rose!

And I told your father about it and he moved his head, you know like he does, from side to side, and he said ‘Let’s hope so, Marge, let’s hope so.’ And now you see!” she concludes triumphantly. “Here’s Ruthey home from the hospital and all well again, and we thought she was in such great danger!”

“Okay!” cries Rose, holding up her hand in an affectionately taunting manner. “That’s the way it was.”

The mother looks up slowly and grins. “All right,” she says now, “you can say what you like, but I understand it better than all of you. I dream, I get nervous when something wrong is going to happen, and when there’s going to be happiness in the house I feel that too—and that’s just what I’ve been feeling all week, ever since I had that dream about Julian. I saw it in the cards too—”

“There she goes!” cries Rose, shaking her head in a gesture of stupefacted defeat. “Now we’re going to hear all about it.”

“It always happens like that,” says the mother firmly, as though the girl had never spoken. “My little Julian tells me all these things. He hasn’t forgotten us and he’s still taking care of us, even though we don’t see him—he’s still here.”

“Aw, Ma knows what she’s talking about, don’t you worry,” says Joe, the eldest son, with a sudden quiet tenderness, as he smiles bashfully at the floor, and paces around the kitchen. “She knows what she knows.”

And the mother, smiling a faint ruminant smile of consolation and joy because her Ruthey is home from the hospital, because she has foreseen it in a dream and in her cards, sits brooding at the kitchen table over her teacup.

The eldest daughter, Rose, is a big husky girl of twenty-one, the “big sister” of the family, the mother’s constant companion and helper, a robust creature full of hilarity and vigor and warmth, possessed of a large and generous nature. She stands by her mother’s side peering anxiously into the icebox, she walks around the kitchen with the heavy steps of a pachyderm that make the dishes in the pantry rattle and jingle, she hauls in the wash in huge baskets from the yard. When her favorite brother, Joe, comes home from his constant wanderings she whoops raucously and chases him around the house. When news comes to the house of catastrophe or great triumph, she exchanges with her mother that swift glance of stunned prophecy.

Tristessa

Tristessa On the Road

On the Road The Dharma Bums

The Dharma Bums Maggie Cassidy

Maggie Cassidy Big Sur

Big Sur Dr. Sax

Dr. Sax Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46

Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46 The Sea Is My Brother

The Sea Is My Brother The Town and the City: A Novel

The Town and the City: A Novel Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Desolation Angels: A Novel

Desolation Angels: A Novel Book of Sketches

Book of Sketches Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha

Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha The Electrocution of Block 38383939383

The Electrocution of Block 38383939383 Haunted Life

Haunted Life Visions of Gerard

Visions of Gerard Orpheus Emerged

Orpheus Emerged Book of Blues

Book of Blues The Subterraneans

The Subterraneans The Haunted Life

The Haunted Life The Unknown Kerouac

The Unknown Kerouac The Town and the City

The Town and the City Visions of Cody

Visions of Cody Atop an Underwood

Atop an Underwood Lonesome Traveler

Lonesome Traveler Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg Vanity of Duluoz

Vanity of Duluoz Desolation Angels

Desolation Angels On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition)

On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition) The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel

The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel Wake Up

Wake Up The Poetry of Jack Kerouac

The Poetry of Jack Kerouac Doctor Sax

Doctor Sax