- Home

- Jack Kerouac

The Poetry of Jack Kerouac

The Poetry of Jack Kerouac Read online

EARLY BIRD BOOKS

FRESH EBOOK DEALS, DELIVERED DAILY

LOVE TO READ?

LOVE GREAT SALES?

GET FANTASTIC DEALS ON BESTSELLING EBOOKS

DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX EVERY DAY!

The Poetry of Jack Kerouac

Scattered Poems, The Scripture of the Golden Eternity, and Old Angel Midnight

Jack Kerouac

CONTENTS

Publisher’s Note on Poetry

Scattered Poems

A TRANSLATION FROM THE FRENCH OF JEAN-LOUIS INCOGNITEAU

Song: FIE MY FUM

PULL MY DAISY

PULL MY DAISY

He is your friend

Old buddy aint you gonna stay by me?

DAYDREAMS FOR GINSBERG

LUCIEN MIDNIGHT

Someday you’ll be lying

I clearly saw

HYMN

POEM: I demand that the human race

THE THRASHING DOVES

The Buddhist Saints

HOW TO MEDITATE

A PUN FOR AL GELPI

SEPT. 16, 1961

RIMBAUD

from OLD ANGEL MIDNIGHT

MORE OLD ANGEL MIDNIGHT

Auro Boralis Shomoheen

LONG DEAD’S LONGEVITY

SITTING UNDER TREE NUMBER TWO

A CURSE AT THE DEVIL

Sight is just dust

POEM

TO EDWARD DAHLBERG

TWO POEMS

TO ALLEN GINSBERG

POEM: Jazz killed itself

TO HARPO MARX

HITCH HIKER

FOUR POEMS from “SAN FRANCISCO BLUES”

from SAN FRANCISCO BLUES

BLUES: And he sits embrowned

BLUES: Part of the morning stars

Hey listen you poetry audiences

SOME WESTERN HAIKUS (from BOOK OF HAIKU)

The Scripture of the Golden Eternity

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

Old Angel Midnight

Dedication

Old Angel Midnight

Editor’s Note

About the Author

Publisher’s Note

Long before they were ever written down, poems were organized in lines. Since the invention of the printing press, readers have become increasingly conscious of looking at poems, rather than hearing them, but the function of the poetic line remains primarily sonic. Whether a poem is written in meter or in free verse, the lines introduce some kind of pattern into the ongoing syntax of the poem’s sentences; the lines make us experience those sentences differently. Reading a prose poem, we feel the strategic absence of line.

But precisely because we’ve become so used to looking at poems, the function of line can be hard to describe. As James Longenbach writes in The Art of the Poetic Line, “Line has no identity except in relation to other elements in the poem, especially the syntax of the poem’s sentences. It is not an abstract concept, and its qualities cannot be described generally or schematically. It cannot be associated reliably with the way we speak or breathe. Nor can its function be understood merely from its visual appearance on the page.” Printed books altered our relationship to poetry by allowing us to see the lines more readily. What new challenges do electronic reading devices pose?

In a printed book, the width of the page and the size of the type are fixed. Usually, because the page is wide enough and the type small enough, a line of poetry fits comfortably on the page: What you see is what you’re supposed to hear as a unit of sound. Sometimes, however, a long line may exceed the width of the page; the line continues, indented just below the beginning of the line. Readers of printed books have become accustomed to this convention, even if it may on some occasions seem ambiguous—particularly when some of the lines of a poem are already indented from the left-hand margin of the page.

But unlike a printed book, which is stable, an ebook is a shape-shifter. Electronic type may be reflowed across a galaxy of applications and interfaces, across a variety of screens, from phone to tablet to computer. And because the reader of an ebook is empowered to change the size of the type, a poem’s original lineation may seem to be altered in many different ways. As the size of the type increases, the likelihood of any given line running over increases.

Our typesetting standard for poetry is designed to register that when a line of poetry exceeds the width of the screen, the resulting run-over line should be indented, as it might be in a printed book. Take a look at John Ashbery’s “Disclaimer” as it appears in two different type sizes.

Each of these versions of the poem has the same number of lines: the number that Ashbery intended. But if you look at the second, third, and fifth lines of the second stanza in the right-hand version of “Disclaimer,” you’ll see the automatic indent; in the fifth line, for instance, the word ahead drops down and is indented. The automatic indent not only makes poems easier to read electronically; it also helps to retain the rhythmic shape of the line—the unit of sound—as the poet intended it. And to preserve the integrity of the line, words are never broken or hyphenated when the line must run over. Reading “Disclaimer” on the screen, you can be sure that the phrase “you pause before the little bridge, sigh, and turn ahead” is a complete line, while the phrase “you pause before the little bridge, sigh, and turn” is not.

Open Road has adopted an electronic typesetting standard for poetry that ensures the clearest possible marking of both line breaks and stanza breaks, while at the same time handling the built-in function for resizing and reflowing text that all ereading devices possess. The first step is the appropriate semantic markup of the text, in which the formal elements distinguishing a poem, including lines, stanzas, and degrees of indentation, are tagged. Next, a style sheet that reads these tags must be designed, so that the formal elements of the poems are always displayed consistently. For instance, the style sheet reads the tags marking lines that the author himself has indented; should that indented line exceed the character capacity of a screen, the run-over part of the line will be indented further, and all such runovers will look the same. This combination of appropriate coding choices and style sheets makes it easy to display poems with complex indentations, no matter if the lines are metered or free, end-stopped or enjambed.

Ultimately, there may be no way to account for every single variation in the way in which the lines of a poem are disposed visually on an electronic reading device, just as rare variations may challenge the

conventions of the printed page, but with rigorous quality assessment and scrupulous proofreading, nearly every poem can be set electronically in accordance with its author’s intention. And in some regards, electronic typesetting increases our capacity to transcribe a poem accurately: In a printed book, there may be no way to distinguish a stanza break from a page break, but with an ereader, one has only to resize the text in question to discover if a break at the bottom of a page is intentional or accidental.

Our goal in bringing out poetry in fully reflowable digital editions is to honor the sanctity of line and stanza as meticulously as possible—to allow readers to feel assured that the way the lines appear on the screen is an accurate embodiment of the way the author wants the lines to sound. Ever since poems began to be written down, the manner in which they ought to be written down has seemed equivocal; ambiguities have always resulted. By taking advantage of the technologies available in our time, our goal is to deliver the most satisfying reading experience possible.

Scattered Poems

The new American poetry as typified by the SF Renaissance (which means Ginsberg, me, Rexroth, Ferlinghetti, McClure, Corso, Gary Snyder, Philip Lamantia, Philip Whalen, I guess) is a kind of new-old Zen Lunacy poetry, writing whatever comes into your head as it comes, poetry returned to its origin, in the bardic child, truly ORAL as Ferling said, instead of gray faced Academic quibbling. Poetry & prose had for long time fallen into the false hands of the false. These new pure poets confess forth for the sheer joy of confession. They are CHILDREN. They are also childlike graybeard Homers singing in the street. They SING, they SWING. It is diametrically opposed to the Eliot shot, who so dismally advises his dreary negative rules like the objective correlative, etc. which is just a lot of constipation and ultimately emasculation of the pure masculine urge to freely sing. In spite of the dry rules he set down his poetry is itself sublime. I could say lots more but aint got time or sense. But SF is the poetry of a new Holy Lunacy like that of ancient times (Li Po, Hanshan, Tom O Bedlam, Kit Smart, Blake) yet it also has that mental discipline typified by the haiku (Basho, Buson), that is, the discipline of pointing out things directly, purely, concretely, no abstractions or explanations, wham wham the true blue song of man.

Jack Kerouac—THE ORIGINS OF JOY IN POETRY

A TRANSLATION FROM THE FRENCH OF JEAN-LOUIS INCOGNITEAU*

My beloved who wills not to love me:

My life which cannot love me:

I seduce both.

She with my round kisses …

(In the smile of my beloved the approbation of the cosmos)

Life is my art …

(Shield before death)

Thus without sanction I live.

(What unhappy theodicy!)

One knows not—

One desires—

Which is the sum.

Allen Ginsberg

*(Kerouac translated by Ginsberg)

1945

Song: FIE MY FUM

Pull my daisy,

Tip my cup,

Cut my thoughts

For coconuts,

Start my arden

Gate my shades,

Silk my garden

Rose my days,

Say my oops,

Ope my shell,

Roll my bones,

Ring my bell,

Pope my parts,

Pop my pot,

Poke my pap,

Pit my plum.

Allen Ginsberg & Jack Kerouac

1950

PULL MY DAISY

Pull my daisy

tip my cup

all my doors are open

Cut my thoughts

for coconuts

all my eggs are broken

Jack my Arden

gate my shades

woe my road is spoken

Silk my garden

rose my days

now my prayers awaken

Bone my shadow

dove my dream

start my halo bleeding

Milk my mind &

make me cream

drink me when you’re ready

Hop my heart on

harp my height

seraphs hold me steady

Hip my angel

hype my light

lay it on the needy

Heal the raindrop

sow the eye

bust my dust again

Woe the worm

work the wise

dig my spade the same

Stop the hoax

what’s the hex

where’s the wake

how’s the hicks

take my golden beam

Rob my locker

lick my rocks

leap my cock in school

Rack my lacks

lark my looks

jump right up my hole

Whore my door

beat my boor

eat my snake of fool

Craze my hair

bare my poor

asshole shorn of wool

say my oops

ope my shell

Bite my naked nut

Roll my bones

ring my bell

call my worm to sup

Pope my parts

pop my pot

raise my daisy up

Poke my pap

pit my plum

let my gap be shut

Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Neal Cassady

1948-1950?

1961

PULL MY DAISY

Pull my daisy

Tip my cup

Cut my thoughts

for coconuts

Jack my Arden

Gate my shades

Silk my garden

Rose my days

Bone my shadow

Dove my dream

Milk my mind &

Make me cream

Hop my heart on

Harp my height

Hip my angel

Hype my light

Heal the raindrop

Sow the eye

Woe the worm

Work the wise

Stop the hoax

Where’s the wake

What’s the box

How’s the Hicks

Rob my locker

Lick my rocks

Rack my lacks

Lark my looks

Whore my door

Beat my beer

Craze my hair

Bare my poor

Say my oops

Ope my shell

Roll my bones

Ring my bell

Pope my parts

Pop my pet

Poke my pap

Pit my plum

Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Neal Cassady

1951, 1958?

1961

He is your friend, let him dream;

He’s not your brother, he’s not yr. father,

He’s not St. Michael he’s a guy.

He’s married, he works, go on sleeping

On the other side of the world,

Go thinking in the Great European Night

I’m explaining him to you my way not yours,

Child, Dog,—listen: go find your soul,

Go smell the wind, go far.

Life is a pity. Close the book, go on,

Write no more on the wall, on the moon,

At the Dog’s, in the sea in the snowing bottom.

Go find God in the nights, the clouds too.

When can it stop this big circle at the skull

oh Neal; there are men, things outside to do.

Great huge tombs of Activity

in the desert of Africa of the heart,

The black angels, the women in bed

with their beautiful arms open for you

in their youth, some tenderness

Begging in the same shroud.

The big clouds of new continents,

O foot tired in climes so mysterious,

Don�

��t go down the otherside for nothing.

1952?

Old buddy aint you gonna stay by me?

Didnt we say I’d die by a lonesome tree

And you come and dont cut me down

But I’m lying as I be

Under a deathsome tree

Under a headache cross

Under a powerful boss

Under a hoss

(my kingdom for a hoss

a hoss

fork a hoss and head

for ole Mexico)

Joe, aint you my buddy thee?

And stay by me, when I fall & die

In the apricot field

And you, blue moon, what you doon

Shining in the sky

With a glass of port wine

In your eye

—Ladies, let fall your drapes

and we’ll have an evening

of interesting rapes

inneresting rapes

1956?

DAYDREAMS FOR GINSBERG

I lie on my back at midnight

hearing the marvelous strange chime

of the clocks, and know it’s mid-

night and in that instant the whole

world swims into sight for me

in the form of beautiful swarm-

ing m u t t a worlds—

everything is happening, shining

Buhudda-lands, bhuti

blazing in faith, I know I’m

forever right & all’s I got to

do (as I hear the ordinary

extant voices of ladies talking

in some kitchen at midnight

oilcloth cups of cocoa

cardore to mump the

rinnegain in his

darlin drain—) i will write

it, all the talk of the world

everywhere in this morning, leav-

ing open parentheses sections

for my own accompanying inner

thoughts—with roars of me

all brain—all world

roaring—vibrating—I put

it down, swiftly, 1,000 words

(of pages) compressed into one second

of time—I’ll be long

robed & long gold haired in

the famous Greek afternoon

of some Greek City

Fame Immortal & they’ll

have to find me where they find

the t h n u p f t of my

shroud bags flying

flag yagging Lucien

Midnight back in their

mouths—Gore Vidal’ll

be amazed, annoyed—

my words’ll be writ in gold

& preserved in libraries like

Tristessa

Tristessa On the Road

On the Road The Dharma Bums

The Dharma Bums Maggie Cassidy

Maggie Cassidy Big Sur

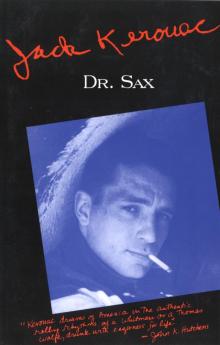

Big Sur Dr. Sax

Dr. Sax Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46

Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46 The Sea Is My Brother

The Sea Is My Brother The Town and the City: A Novel

The Town and the City: A Novel Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Desolation Angels: A Novel

Desolation Angels: A Novel Book of Sketches

Book of Sketches Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha

Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha The Electrocution of Block 38383939383

The Electrocution of Block 38383939383 Haunted Life

Haunted Life Visions of Gerard

Visions of Gerard Orpheus Emerged

Orpheus Emerged Book of Blues

Book of Blues The Subterraneans

The Subterraneans The Haunted Life

The Haunted Life The Unknown Kerouac

The Unknown Kerouac The Town and the City

The Town and the City Visions of Cody

Visions of Cody Atop an Underwood

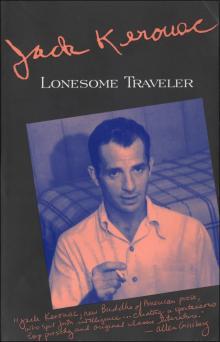

Atop an Underwood Lonesome Traveler

Lonesome Traveler Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg Vanity of Duluoz

Vanity of Duluoz Desolation Angels

Desolation Angels On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition)

On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition) The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel

The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel Wake Up

Wake Up The Poetry of Jack Kerouac

The Poetry of Jack Kerouac Doctor Sax

Doctor Sax