- Home

- Jack Kerouac

Visions of Cody

Visions of Cody Read online

Penguin Books

Visions of Cody

Jack Kerouac was born in Lowell, Massachusetts, in 1922, the youngest of three children in a Franco-American family. He attended local Catholic and public schools and won a football scholarship to Columbia University in New York City, where he first met Neal Cassady, Allen Ginsberg, and William S. Burroughs. He quit school in his sophomore year after a dispute with his football coach, and joined the Merchant Marine, beginning the restless wanderings that were to continue for the greater part of his life. His first novel, The Town and the City, appeared in 1950, but it was On the Road, first published in 1957 and memorializing his adventures with Neal Cassady, that epitomized to the world what became known as “the Beat generation” and made Kerouac one of the most controversial and best-known writers of his time. Publication of his many other books followed, among them The Dharma Bums, The Subterraneans, and Big Sur. Kerouac considered them all to be part of The Duluoz Legend. “In my old age,” he wrote, “I intend to collect all my work and reinsert my pantheon of uniform names, leave the long shelf full of books there, and die happy.” He died in St. Petersburg, Florida, in 1969, at the age of forty-seven.

By Jack Kerouac

The Town and the City

The Scripture of the Golden Eternity

Some of the Dharma

Old Angel Midnight

Good Blonde and Others

Pull My Daisy

Trip Trap

Pic

The Portable Jack Kerouac

Selected Letters: 1940–1956

Selected Letters: 1957–1969

Atop and Underwood

Orpheus Emerged

POETRY

Mexico City Blues

Scattered Poems

Pomes All Sizes

Heaven and Other Poems

Book of Blues

Book of Haikus

THE DULUOZ LEGEND

Visions of Gerard

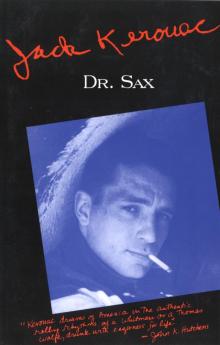

Doctor Sax

Maggie Cassidy

Vanity of Duluoz

On the Road

Visions of Cody

The Subterraneans

Tristessa

Lonesome Traveller

Desolation Angels

The Dharma Bums

Book of Dreams

Big Sur

Satori in Paris

Jack Kerouac

Visions of Cody

With THE VISIONS OF THE GREAT REMEMBERER

by Allen Ginsberg

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10014

USA * Canada * UK * Ireland * Australia

New Zealand * India * South Africa * China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

First published in the United States of America by McGraw-Hill Company 1972

This edition with “The Visions of the Great Rememberer” by Allen Ginsberg published in Penguin Books 1993

Copyright © Jack Kerouac, 1960

Copyright © the Estate of Jack Kerouac, 1972

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA

Kerouac, Jack, 1922–1969.

Visions of Cody/Jack Kerouac. With The visions of the great rememberer/by Allen Ginsberg.

p. cm.

ISBN: 978-1-101-54878-3

1. Beat generation—Fiction. 2. Kerouac, Jack, 1922–1969—Biography. 3. Authors, American—20th century—Biography. 4. Beat generation—Biography. I. Ginsberg, Allen, 1926– Visions of the great rememberer. 1993. II. Title. III. Title: Visions of the great rememberer.

PS3521.E735V5 1993

813.54—dc20 93–22466

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint the following copyrighted works:

Excerpt from “Good Morning Heartache” by Irene Higginbotham, Ervin Drake and Dan Fisher. © Copyright 1946 by Northern Music Company, a division of MCA Entertainment Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Excerpt from “Them There Eyes” by Maceo Pinkard, William Tracy and Doris Tauber. © 1930 Bourne Co., copyright renewed. Used by permission.

Excerpt from “Lover” by Lorenz Hart and Richard Rodgers. Copyright © 1932 and 1933 by Famous Music Corporation. Copyright renewed 1959 and 1960 by Famous Music Corporation. Used by permission.

The quotations from the poems on pages 325–326 are used with the permission of Allen Ginsberg.

“The Visions of the Great Rememberer” by Allen Ginsberg. Copyright © 1974 by Allen Ginsberg. Reprinted with permission of the author.

Dedicated to America, whatever that is

Visions of Cody is a 600-page character study of the hero of On the Road, “Dean Moriarty,” whose name now is “Cody Pomeray.” I wanted to put my hand to an enormous paean which would unite my vision of America with words spilled out in the modern spontaneous method. Instead of just a horizontal account of travels on the road, I wanted a vertical, metaphysical study of Cody’s character and its relationship to the general “America.” This feeling may soon be obsolete as America enters its High Civilization period and no one will get sentimental or poetic any more about trains and dew on fences at dawn in Missouri. This is a youthful book (1951) and it was based on my belief in the goodness of the hero and his position as an archetypical American Man. The tape recordings in here are actual transcriptions I made of conversations with Cody who was so high he forgot the machine was turning. Dean Moriarty becomes Cody Pomeray, Sal Paradise becomes Jack Duluoz, Carlo Marx becomes Irwin Garden and so on in all of my work from now on, published and unpublished (with the exception of the 1950 fictional novel The Town and the City). My work comprises one vast book like Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past except that my remembrances are written on the run instead of afterwards in a sick bed. Because of the objections of my early publishers I was not allowed to use the same personae names in each work. On the Road, The Subterraneans, The Dharma Bums, Doctor Sax, Maggie Cassidy, Tristessa, Desolation Angels and the others are just chapters in the whole work which I call The Duluoz Legend. In my old age I intend to collect all my work and reinsert my pantheon of uniform names, leave the long shelf full of books there, and die happy. The whole thing forms one enormous comedy, seen through the eyes of poor Ti Jean (me), otherwise known as Jack Duluoz, the world of raging action and folly and also of gentle sweetness seen through the keyhole of his eye.

Jack Kerouac

Table of Contents

1

2

3

1

THIS IS AN OLD DINER like the ones Cody and his father ate in, long ago, with that oldfashioned railroad car ceiling and sliding doors—the board where bread is cut is worn down fine as if with bread dust and a plane; the icebox (“Say I got some nice homefries tonight Cody!”) is a huge brownwood thing with oldfashioned pull-out handles, windows, tile walls, full of lovely pans of eggs, butter pats, piles of bacon—old lunchcarts always have a dish of sliced raw onions ready to go on hamburgs. Grill is ancient and dark and emits an odor which is really succulent, like you would expect from the black hide of an old ham or an old pastrami beef—The lunchcart has stools with smooth slickwood tops—there are wooden drawers for where you find the long loaves of sandwich bread—The countermen: either Greeks or

have big red drink noses. Coffee is served in white porcelain mugs—sometimes brown and cracked. An old pot with a half inch of black fat sits on the grill, with a wire fryer (also caked) sitting in it, ready for french fries—Melted fat is kept warm in an old small white coffee pot. A zinc siding behind the grill gleams from the brush of rags over fat stains—The cash register has a wooden drawer as old as the wood of a rolltop desk. The newest things are the steam cabinet, the aluminum coffee urns, the floor fans—But the marble counter is ancient, cracked, marked, carved, and under it is the old wood counter of late twenties, early thirties, which had come to look like the bottoms of old courtroom benches only with knifemarks and scars and something suggesting decades of delicious greasy food. Ah!

The smell is always of boiling water mixed with beef, boiling beef, like the smell of the great kitchens of parochial boarding schools or old hospitals, the brown basement kitchens’ smell—the smell is curiously the hungriest in America—it is FOODY insteady of just spicy, or—it’s like dishwater soap just washed a pan of hamburg—nameless—memoried—sincere—makes the guts of men curl in October.

* * *

THE CAPRICIO B-MOVIE: the glass facings on the marquee, over which the movable letters are slid, are in places broken so that you can see bulbs inside and some of the bulbs broken; further the letters always misspell—Short Subjets etc.—Alwa ystwo big features (the letters misplaced as well) so that from a distance you see this spotty marquee (it is supported from the brick face of the building by iron black sooty hooks and bars—just behind marquee top a nameless window with a dusty heavy wire screen, probably projection room)—from a distance you can’t read it and it’s been spelled out by crazy dumb kids who earn eighteen dollars a week and know Cody and it looks like a B-movie. The sidewalk in front is dirty, has banana peels and the old splashmarks of puke or broken milk bottles—the lobby has a tile floor—a torn rubber carpet leading to ticket box, which is as ornate as something from a carnival and curlicued and painted gaudy orange-brown (just because for tickets); bespectacled middleaged Jewish proprietor takes tickets. The pictures in the sidewall slides are always the same, terrible B-movies—twelve installment serials, western or fantastic and cheap—Negro boys spar in front. Across the street is an old beat gas station—diner on the other corner—right next to movie is a hotdog-Coke-magazine establishment with a big scarred Coca-Cola sign at base of an open counter topped by a marble now so old that it has turned gray and chipped, covered with bottles of syrup to make soda drinks and ad cards and junk, and beneath, an ancient woodflap once used to close place at night, now nailed under Coca-Cola, is so weatherbeaten and old, and was once painted brown, that it now has a shapeless color like shit against the gray, almost shit-gray sidewalk which is covered with butts and gumwrappers itself. This is the bottom of the world, where little raggedy Codys dream, as rich men plan gleaming plastic auditoriums and soaring glass fronts on Park Avenue and the rich districts of Denver and the world.

* * *

IN THE AUTUMN OF 1951 I began thinking of Cody Pomeray, thinking of Cody Pomeray. We had been great buddies on the road. I was in New York and I wanted to go to California and see him, but I had no money. I’m in an old El station on Third Avenue and 47th, sitting in wooden sunken-seat benches along the walls—the Porter sign in the door is almost all faded—In the raw wood wall a strange beautiful window with blue and red stained glass fringes—two bare bulbs on each side of it—the floor old worn planks—the whole place shakes as the train approaches. A huge old iron potbelly stove, its iron showing through grayish (not polished for years)—the stovepipe goes up four feet then over seven feet (climbing slightly) then up two feet to disappear into the fantastic ceiling of carved wood, into some kind of chimney flue characterized by a circular cover with carved openings—the stove sits on an ancient pad, and the floor sags away from it. At the wall tops along ceiling are carved raw buttresses like in Victorian porches. The place is so brown that any light looks brown in it—It’s fit for the sorrows of winter night and reminds me speechlessly of old blizzards when my father was ten, of “’88” or some such and of old workmen spitting and Cody’s father. Outside—sprawling “alpine lodge” crazy crooked wood house with fringes, weathervane tower, vane itself, pale shapeless snot green, stained with ages of rain and snow, onetime red (now forlorn hint of red) tower—fringes elaborate as hell—timbers on tracks are splintered and aged beyond recognition.

* * *

AND OVER AT THIRD AVENUE AND 9th STREET is a beat employment agency, it’s over a music store which (Western Music Co.) has a dirty piss splashed and littered sooty sidewalk in front, and iron cellar sidewalk doors also filthy and sag when you walk over. Western Music Co. written in white against green glass with lights behind but so sooty is the white part it makes a dirty sad effect.

Old newspapers and old paper container tops, piled up in corner of door, maybe by bum, wind or child. In the window is a big bass drum, used, faded—saxes—old fiddles—Tuba sitting on tinfoil (attempt to brighten window sensationally, drastically like they do in wildest modern stores). Bongos—guitar—regular old black and white linoleum (one-foot squares) is bottom of show window. Entrance to W.E.A. is to left—Sign is long vertical wedge sign, black on yellow, says Central Employment Agency—Black with dust planking is hall leading in—Sign says (34 is the number)—chefs, cooks, bakers, waiters, bartenders, etc.—In the office (brown light) sits a shirtsleeve vest brownsuit boss at desk (with bowtie, cropped gray hair) as two beat clients wait in blue leather chairs—one of them is old white-hair guy in Scandinavian ski sweater. Other is dark, beat Greek in dark suit offset by white shirt and blue snazzy tie—An unused desk among the three altogether has a green blotter on it torn in middle, raveled up, showing undercardboard—rough plaster stonewalls are painted brown and yellow—folded newspapers lie about—third beat guy being interviewed, sits on radiator covering with back to big plate glass window that faces old El station where watchers linger for nothing (or for next door weird factory shop where fat men in aprons are making labels for dolls). Boss uses phone, guy sitting (with open sports collar and Army-Navy Store suit) big, like boxer, waits all hunched forward with palms on knees—

Building is ancient red—1880 redbrick—three stories—over its roof I can see cosmic Italian oldfashioned eighteen-story office block building with ornaments and blueprint lights inside that reminds me of eternity, the enormous house of dusk where everybody is putting on their coats—and going down black stairs like fire escapes to eat supper in the dungeon of Time underneath just a few feet over the Snake—and Doctor Sax clambers over the wallsides as night falls, with his suction cups—and the superintendent is sleeping.

Meanwhile, next door to the music store is a shoe repair, closed and dark now, then the Harmony Bar and Grill in crimson neon upon the gray sidewalk.

* * *

THE MEN’S ROOM in Third Avenue El has wood walls painted green (for wainscot effect this), yellow up to old carved wooden ceiling—stench of piss is like ammonia—piss in urinal sloshes as train, arriving, shakes the place—high on wall where yellow paint is, a big coathook decked with soot (like snow that’s fallen on a twig) and fully a foot long, like seeing an enormous cockroach—and too high to reach—toilet bowl has oldfashioned outhouse plank with hole to lower—bowl strangely surrounded by a fence of piping, like a park—same stained glass window but unwashed and has chain you pull it open with, like flushing out—The wainscot effect of dark then yellow up to ceiling is also to be found in the clock-tocking reading rooms of flophouses like the Skylark in Denver where Cody and his father stayed where bums sit on creaky chairs and with their cloth caps settin straight on their heads and still covered with grease spots probably from Montana they grimly read the papers to show that tonight they are not goofing in no alleys with rotgut and in fact they’ve just eaten supper in the restaurant with all the cheap prices soaped-in on the plate glass windows—Soup, 50¢, Italian spaghetti, 20¢ knockwurst and beans, 25¢ (bent

over their plates and gobbled food with big grimy sad hands, gripping, old cloth capped heads bent in pitiful congregation, the needs and necessities, no “dining” here) in fact the most woebegone bignosed bum in the world, enormous red nose that in fact he snicked out as he came out of the eatery to cap the horror of it—a big clown caricature of the Hawk—had eaten 20¢ worth ’cause I saw him lay it on the counter and let it go reluctantly, spaghetti or the vegetable dinner plate, portions seemed to be awright inside, three slices of bread not two, I saw heaps of boiled potatoes alongside meat as those heartbreaking poor guys in their inconceivable clothes, World-War-I Army greatcoats, black baseball caps too small like Cody’s father’s with a witless peak, leaned elbows over their humble meals of grime—I saw the flash of their mouths, like the mouths of minstrels, as they ate…the bignose bum moved away from his 20¢ at a very (pitiful tomato “salads”) slow, slow shuffle, sort of eased himself from the area of the restaurant to the area of the sidewalk, where in the chill October with winter coming he shuffled right along in his white shirtsleeves nothing else and drab pants like the pants of Dutch bums in windmills and dung, his head bent as if from the weight of the immense melancholy nose (twice as big as W. C. Fields!)—(no hope, “no-good” pedestrians on all sides). The wainscots of flophouses—I was amazed by them “adventurous slouched hats”—ages of rain make their brims roll up and down willy-nilly and yet just because it’s these damn old cowboys wearing them the hats retain immense indefinable charm of the wideopen free sprawling America of railroads and distant mesas—that Australian, that pioneer, that frontier dash is worked in by the rain—on their slanted farlooking heads. And they are adventurous, one guy against the wall has same look you see on kid of eleven having first cornsilk butt along garage wall after supper in the interesting darkness in Eau Claire, Wisconsin—same wickedness, as if the world was his mother remonstrating with him—same look of adventuring you see on young truckdrivers when they stop at a lonely junction Coke stand at night in Texas and their enormous truck-trailer sits waiting for them huge across the road, with a spare tire regardant under the cab like the ram shield on a Dodge radiator cap—the flying billy ram of travel—and both of ’em dirty and grim and come a long way and quiet and Henry-Fonda-like and talk to each other that you can’t hear and when they leave together they move with the same sadness as if their adventure together was persecuting them to grieve the same careful way and off they go into their own night beyond the whatevers of where you who watch them still stay, they are gone yonder never to come back again and have come and gone like ghosts across your eyes and the bums have that same grave, careful adventurous sorrow as they stand stiffly before an alley wall looking straight ahead with their eyes and their drinkwet mouths glistening in the moonlight in a lunar Bowery, spitting or saying “Hey sport, gimme a dime for a goddamn cup of coffee,” and in it there is a statement “I’ve come a long, long way to be standing against this wall—stranger—and you ought to ’predate the troubles I’ve had and the miles I done—’cause after all I’m from a Houston and you’re a damn New Yorker that ain’t never been to God’s country Texas—”

Tristessa

Tristessa On the Road

On the Road The Dharma Bums

The Dharma Bums Maggie Cassidy

Maggie Cassidy Big Sur

Big Sur Dr. Sax

Dr. Sax Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46

Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46 The Sea Is My Brother

The Sea Is My Brother The Town and the City: A Novel

The Town and the City: A Novel Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Desolation Angels: A Novel

Desolation Angels: A Novel Book of Sketches

Book of Sketches Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha

Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha The Electrocution of Block 38383939383

The Electrocution of Block 38383939383 Haunted Life

Haunted Life Visions of Gerard

Visions of Gerard Orpheus Emerged

Orpheus Emerged Book of Blues

Book of Blues The Subterraneans

The Subterraneans The Haunted Life

The Haunted Life The Unknown Kerouac

The Unknown Kerouac The Town and the City

The Town and the City Visions of Cody

Visions of Cody Atop an Underwood

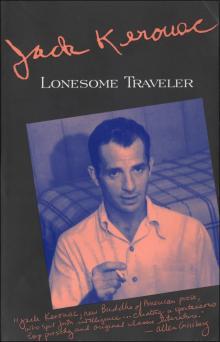

Atop an Underwood Lonesome Traveler

Lonesome Traveler Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg Vanity of Duluoz

Vanity of Duluoz Desolation Angels

Desolation Angels On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition)

On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition) The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel

The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel Wake Up

Wake Up The Poetry of Jack Kerouac

The Poetry of Jack Kerouac Doctor Sax

Doctor Sax