- Home

- Jack Kerouac

Vanity of Duluoz

Vanity of Duluoz Read online

PENGUIN BOOKS

VANITY OF DULUOZ

Jack Kerouac was born in Lowell, Massachusetts, in 1922, the youngest of three children in a Franco-American family. He attended local Catholic and public schools and won a football scholarship to Columbia University in New York City, where he first met Neal Cassady, Allen Ginsberg, and William S. Burroughs. He quit school in his sophomore year after a dispute with his football coach, and joined the Merchant Marine, beginning the restless wanderings that were to continue for the greater part of his life. His first novel, The Town and the City, appeared in 1950, but it was On the Road, first published in 1957 and memorializing his adventures with Neal Cassady, that epitomized to the world what became known as “the Beat generation” and made Kerouac one of the most controversial and best-known writers of his time. Publication of his many other books followed, among them The Dharma Bums, The Subterraneans, and Big Sur. Kerouac considered them all to be part of The Duluoz Legend. “In my old age,” he wrote, “I intend to collect all my work and reinsert my pantheon of uniform names, leave the long shelf full of books there, and die happy.” He died in St. Petersburg, Florida, in 1969, at the age of forty-seven.

By Jack Kerouac

The Town and the City

The Scripture of the Golden Eternity

Some of the Dharma

Old Angel Midnight

Good Blonde and Others

Pull My Daisy

Trip Trap

Pic

The Portable Jack Kerouac

Selected Letters: 1940–1956

Selected Letters: 1957–1969

Atop an Underwood

Orpheus Emerged

POETRY

Mexico City Blues

Scattered Poems

Pomes All Sizes

Heaven and Other Poems

Book of Blues

Book of Haikus

THE DULUOZ LEGEND

Visions of Gerard

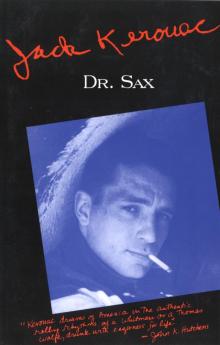

Doctor Sax

Maggie Cassidy

Vanity of Duluoz

On the Road

Visions of Cody

The Subterraneans

Tristessa

Lonesome Traveller

Desolation Angels

The Dharma Bums

Book of Dreams

Big Sur

Satori in Paris

JACK KEROUAC

Vanity of Duluoz

An Adventurous Education, 1935–46

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Books (N.Z.) Ltd, Cnr Rosedale and Airborne Roads, Albany, Auckland, New Zealand

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in the United States of America by Coward-McCann 1968

Published in Penguin Books 1994

20 19 18 17 16

Copyright © Jack Kerouac, 1967, 1968

All rights reserved

ISBN 9781101548431

(CIP data available)

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

DEDICATED TO

Means ‘From the Cross’ in Greek, and is also my wife’s first name – STAVROULA.

Extra, special thanks to Ellis Amburn for his emphatic brilliance and expertise.

Book One

I

All right, wifey, maybe I’m a big pain in the you-know-what but after I’ve given you a recitation of the troubles I had to go through to make good in America between 1935 and more or less now, 1967, and although I also know everybody in the world’s had his own troubles, you’ll understand that my particular form of anguish came from being too sensitive to all the lunkheads I had to deal with just so I could get to be a high school football star, a college student pouring coffee and washing dishes and scrimmaging till dark and reading Homer’s Iliad in three days all at the same time, and God help me, a WRITER whose very ‘success’, far from being a happy triumph as of old, was the sign of doom Himself. (Insofar as nobody loves my dashes anyway, I’ll use regular punctuation for the new illiterate generation.)

Look, furthermore, my anguish as I call it arises from the fact that people have changed so much, not only in the past five years, for God’s sake, or past ten years as McLuhan says, but in the past thirty years to such an extent that I don’t recognize them as people any more or recognize myself as a real member of something called the human race. I can remember in 1935 when fullgrown men, hands deep in jacket pockets, used to go whistling down the street unnoticed by anybody and noticing no one themselves. And walking fast, too, to work or store or girlfriend. Nowadays, tell me, what is this slouching stroll people have? Is it because they’re used to walking across parking-lots only? Has the automobile filled them with such vanity that they walk like a bunch of lounging hoodlums to no destination in particular?

Autumn nights in Massachusetts before the war you’d always see a guy going home for supper with his fists buried deep in the sidepockets of his jacket, whistling and striding along in his own thoughts, not even looking at anybody else on the sidewalk and after supper you’d always see the same guy rushing out the same way, headed for the corner candy store, or to see Joe, or to a movie or to a poolroom or the deadman’s shift in the mills or to see his girl. You no longer see this in America, not only because everybody drives a car and goes with stupid erect head guiding the idiot machine through the pitfalls and penalties of traffic, but because nowadays no one walks with unconcern, head down, whistling; everybody looks at everybody else on the sidewalk with guilt and worse than that, curiosity and faked concern, in some cases ‘hip’ regard based on ‘Dont miss a thing’, while in those days there even used to be movies of Wallace Beery turning over in bed on a rainy morning and saying: ‘Aw gee, I’m going back to sleep, I aint gonna miss anything anyway.’ And he never missed a thing. Today we hear of ‘creative contributions to society’ and nobody dares sleep out a whole rainy day or dares think they’ll really miss anything.

That whistling walk I tell you about, that was the way grownup men used to walk out to Dracut Tigers field in Lowell Mass. on Saturdays and Sundays just to go see a kids’ sandlot football game. In the cold winds of November, there they are, men and boys, sidelines; some nut’s even made a homemade sideline chain with two pegs to measure the downs – that is to say, the gains. In football when your team gains 10 yards they get another four chances to gain 10 more. Somebody has to keep tabs by rushing out on the field when it’s close and measuring accurately how much ground is left. For that you have to have two guys holding each end of the chain by the two pegs, and they have to know how to run out according to parallel instinct. Today I doubt if anybody in the Man

dala Mosaic Meshed-Up world knows what parallel means, except brilliant nuts in college mathematics, surveyors, carpenters, etc.

So here comes this mob of carefree men and boys too, even girls and quite a few mothers, hiking a mile across the meadow of Dracut Tigers field just to see their boys of thirteen and seventeen play football in an up-and-down uneven field with no goalposts, measured off for 100 yards more or less by a pine tree on one end and a peg on the other.

But in my first sandlot game in 1935, about October, no such crowd: it was early Saturday morning, my gang had challenged the so-and-so team from Rosemont, yes, in fact it was the Dracut Tigers (us) versus the Rosemont Tigers, Tigers everywhere, we’d challenged them in the Lowell Sun newspaper in a little article written in by our team captain, Scotcho Boldieu and edited by myself: ‘The Dracut Tigers, age 13 to 15, challenge any football team age 13 to 15, to a game in Dracut Tigers field or any field Saturday Morning.’ It was no official league or anything, just kids, and yet the bigger fellows showed up to keep official measurement of the yardage with their chain and pegs.

In this game, although I was probably the youngest player on the field, I was also the only big one, in the football sense of bigness, i.e., thick legs and heavy body. I scored nine touchdowns and we won 60–0 after missing 3 points after. I thought from that morning on, I would be scoring touchdowns like that all my life and never be touched or tackled, but the serious football was coming up that following week when the bigger fellows who hung around my father’s poolhall and bowling alley at the Pawtucketville Social Club decided to show us something about bashing heads. Their reason, some of them, to show was that my father kept throwing them out of the club because they never had a nickel for a Coke or a game of pool, or a dime for a string of bowling, and just hung around smoking with their legs stuck out, blocking the passage of the real habitués who came there to play. Little I knew of what was coming up, that morning after nine touchdowns, as I rushed up to my bedroom and wrote down by hand, in neat print, a big newspaper headline and story announcing DULUOZ SCORES 9 TOUCHDOWNS AS DRACUT CLOBBERS ROSEMONT 60–0! This newspaper, the only copy, I sold for three cents to Nick Rigolopoulos, my only customer. Nick was a sick man of about thirty-five who liked to read my newspapers since he had nothing else to do and was soon to be in a wheelchair.

Comes the big game, when, as I say, men with hands-a-pockets came a-whistling and laughing across the field, with wives, daughters, gangs of other men, boys, all to line up along the sidelines, to watch the sensational Dracut Tigers try on a tougher team.

Fact is, the ‘poolhall’ team averaged the ages of sixteen to eighteen. But I had some tough boys in my line. I had Iddyboy Bissonnette, as my centre, who was bigger and older than I was but preferred not to run in the backfield, liked, instead, the bingbang inside the line, to open holes for the runners. He was hard as a rock and would have been one of the greatest linemen in the history of Lowell High football later on if his marks had not averaged E or D-minus. My quarterback was the clever strong little Scotcho Boldieu who could pass beautifully (and was a wonderful pitcher in baseball later). I had another wiry strong kid called Billy Artaud who could really hit a runner and when he did so, bragged about it for a week. I had others less effectual, like Dicky Hampshire who one morning actually played in his best suit (at right end) because he was on his way to a wedding, and was afraid to get his suit dirty, so let nobody touch him and touched no one. I had G. J. Rigolopoulos who was pretty good when he got sore. For the big game I managed to recruit Bong Baudoin from the now-defunct Rosemont Tigers, and he was strong. But we were all thirteen and fourteen.

On the kickoff I caught the ball and ran in and got swarmed under by the big boys. In the pileup, with me underneath clutching the ball, suddenly seventeen-year-old Halmalo, the poolhall kickout, was punching me in the face under cover of the bodies and saying to his pals ‘Get the little Christ of a Duluoz.’

My father was on the sidelines and saw it. He strode up and down puffing on his cigar, face red with rage. (I’m going to write like this to simplify matters.) After three unsuccessful downs we have to punt, do so, the safety man of the older boys runs back a few yards and it’s their first down. I tell Iddyboy Bissonnette about the punch in the pileup. They make their first play and somebody in the older boys’ line gets up with a bloody nose. Everybody’s mad.

On the next play Halmalo receives the ball from center and starts waltzing around his left end, longlegged and thin, with good interference, thinking he’s going to go all the way against these punk kids. Running low, I come up, so low his interference thinks in their exertion that I’m fallen on my knees, and when they split a bit to go hit others to open the way for Halmalo, I dive through that hole and come up on him head on, right at the knees, and drive him some 10 yards back sliding on his arse with the ball scattered into the sidelines and himself out like a light.

He’s carried off the field unconscious.

My father yells ‘Ha ha ha, that’ll teach you to punch a thirteen-year-old boy mon maudit crève faim!’ (Last part in Canadian French, and means, more or less, ‘you damned starveling of the spirit’.)

II

I really forget the score in that game, I think we won; if I went down to the Pawtucketville Social Club to find out I dont think anybody’d remember and certainly do know everybody’d lie. The reason I’m so bitter and, as I said, ‘in anguish’, nowadays, or one of the reasons, is that everybody’s begun to lie and because they lie they assume that I lie too: they overlook the fact that I remember very well many things (of course I’ve forgotten some, like that score), but I do believe that lying is a sin, unless it’s an innocent lie based on lack of memory, certainly the giving of false evidence and being a false witness is a mortal sin, but what I mean is, insofar as lying has become so prevalent in the world today (thanks to Marxian Dialectical propaganda and Comintern techniques among other causes) that, when a man tells the truth, everybody, looking in the mirror and seeing a liar, assumes that the truth-teller is lying too. (Dialectical Materialism and the Comintern techniques were the original tricks of Bolshevist Communism, that is, you have the right to lie if you’re on the Bullshivitsky side.) Thus that awful new saying: ‘You’re putting me on.’ My name is Jack (‘Duluoz’) Kerouac and I was born in Lowell Mass. on 9 Lupine Road on March 12, 1922. ‘Oh you’re putting me on.’ I wrote this book Vanity of Duluoz. ‘Oh you’re putting me on.’ It’s like that woman, wifey, who wrote me a letter awhile ago saying, of all things, and listen to this:

‘You are not Jack Kerouac. There is no Jack Kerouac. His books were not even written.’

They just suddenly appeared on a computer, she probably thinks, they were programmed, they were fed informative confused data by mad bespectacled egghead sociologists and out of the computer came the full manuscript, all neatly typed doublespace, for the publisher’s printer to simply copy and the publisher’s binder to bind and the publisher to distribute, with cover and blurb jacket, so this inexistent ‘Jack Kerouac’ could not only receive two-dollar royalty check from Japan but also this woman’s letter.

Now David Hume was a great philosopher, and Buddha was right in the eternal sense, but this is going a little bit too far. Of course it’s true that my body is nothing but an electro-magnetic gravitational field, like that yonder table, and of course it’s true that the mind is really nonexistent in the sense of the old Dharma Masters like Hui-Neng; but on the other hand, who is he that is not ‘he’ because of an idiot’s ignorance?

III

This recitation of my complaints aint even begun yet; no fear, I wont be longwinded. This beef I’m putting in here is about the fact that Halmalo, or whatever his name really was, called me that ‘little Christ of a Duluoz’, which was a blasphemy that went with his secret punch in the mouth. And that today nobody believes this story. And that today nobody walks hands-in-pockets whistling across fields or even down sidewalks. That long before

I’ll lose track of my beefs I’ll go cracked and even get to believe, like those LSD heads in newspaper photographs who sit in parks gazing rapturously at the sky to show how high they are when they’re only victims momentarily of a contraction of the blood vessels and nerves in the brain that causes the illusion of a closure (a closing-up) of outside necessities, get to thinking I’m not Jack Duluoz at all and that my birth records, my family’s birth records and recorded origins, my athletic records in the newspaper clippings I have, my own notebooks and published books, are not real at all, but all lies, nay, that my own dreams dreamed at night in sleep are not dreams at all but inventions of my waking imagination, that I am not ‘I am’ but just a spy in somebody’s body pretending I’m an elephant going through Istanbul with natives caught in its toes.

IV

All footballers know that the best football players started on sandlots. Take Johnny Unitas for instance, who never even went to high school, and take Babe Ruth too in baseball. From those early sandlot games we went on to some awful blood-flying games in North Common against the Greeks: the North Common Panthers. Naturally when a Canuck like Leo Boisleau (now on my team) and a Greek like Socrates Tsoulias come head on, blood will fly. The blood my dear flew like in a Homeric battle those Saturday mornings. Imagine Putsy Keriakalopoulos trying to dance his way on that dusty crazy field around Iddyboy or a crazy charging bull like Al Didier. It was the Canucks against the Greeks. The beauty of it all, these two teams later formed the nucleus of the Lowell High School football team. Imagine me trying to dive off tackle through Orestes Gringas or his brother Telemachus Gringas. Imagine Christy Kelakis trying to lay a pass over the fingers of tall Al Roberts. These later sandlot games were so awful I was afraid to get up on Saturday mornings and show up. Other games were played in Bartlett Junior High field, where we’d all gone as kids, some in Dracut Tigers field, some in the cowfield near St Rita’s Church. There were other, wilder Canuck teams from around Salem Street who never contacted us because they didn’t know how to ask for a game via the sports page of the newspaper; otherwise I think the combination of their team with ours, and the combination of other Greek or even Polish or Irish teams around town . . . O me, in other words, Homeric wouldnt have been the word for it.

Tristessa

Tristessa On the Road

On the Road The Dharma Bums

The Dharma Bums Maggie Cassidy

Maggie Cassidy Big Sur

Big Sur Dr. Sax

Dr. Sax Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46

Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46 The Sea Is My Brother

The Sea Is My Brother The Town and the City: A Novel

The Town and the City: A Novel Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Desolation Angels: A Novel

Desolation Angels: A Novel Book of Sketches

Book of Sketches Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha

Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha The Electrocution of Block 38383939383

The Electrocution of Block 38383939383 Haunted Life

Haunted Life Visions of Gerard

Visions of Gerard Orpheus Emerged

Orpheus Emerged Book of Blues

Book of Blues The Subterraneans

The Subterraneans The Haunted Life

The Haunted Life The Unknown Kerouac

The Unknown Kerouac The Town and the City

The Town and the City Visions of Cody

Visions of Cody Atop an Underwood

Atop an Underwood Lonesome Traveler

Lonesome Traveler Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg Vanity of Duluoz

Vanity of Duluoz Desolation Angels

Desolation Angels On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition)

On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition) The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel

The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel Wake Up

Wake Up The Poetry of Jack Kerouac

The Poetry of Jack Kerouac Doctor Sax

Doctor Sax