- Home

- Jack Kerouac

Tristessa

Tristessa Read online

PENGUIN BOOKS

TRISTESSA

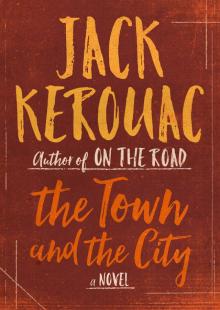

Jack Kerouac was born in Lowell, Massachusetts, in 1922, the youngest of three children in a Franco-American family. He attended local Catholic and public schools and won a football scholarship to Columbia University in New York City, where he first met Neal Cassady, Allen Ginsberg, and William S. Burroughs. He quit school in his sophomore year after a dispute with his football coach, and joined the Merchant Marine, beginning the restless wanderings that were to continue for the greater part of his life. His first novel, The Town and the City, appeared in 1950, but it was On the Road, first published in 1957 and memorializing his adventures with Neal Cassady, that epitomized to the world what became known as “the Beat generation” and made Kerouac one of the most controversial and best-known writers of his time. Publication of his many other books followed, among them The Dharma Bums, The Subterraneans, and Big Sur. Kerouac considered them all to be part of The Duluoz Legend. “In my old age,” he wrote, “I intend to collect all my work and reinsert my pantheon of uniform names, leave the long shelf full of books there, and die happy.” He died in St. Petersburg, Florida, in 1969, at the age of forty-seven.

BY JACK KEROUAC

The Town and the City

The Scripture of the Golden Eternity

Some of the Dharma

Old Angel Midnight

Good Blonde and Others

Pull My Daisy

Trip Trap

Pic

The Portable Jack Kerouac

Selected Letters: 1940–1956

Selected Letters: 1957–1969

Atop an Underwood

Orpheus Emerged

POETRY

Mexico City Blues

Scattered Poems

Pomes All Sizes

Heaven and Other Poems

Book of Blues

Book of Haikus

THE DULUOZ LEGEND

Visions of Gerard

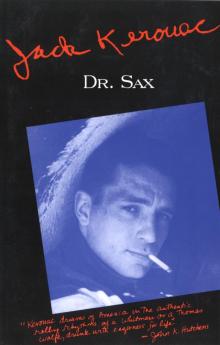

Doctor Sax

Maggie Cassidy

Vanity of Duluoz

On the Road

Visions of Cody

The Subterraneans

Tristessa

Lonesome Traveller

Desolation Angels

The Dharma Bums

Book of Dreams

Big Sur

Satori in Paris

TRISTESSA

Jack Kerouac

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto,

Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell,

Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi - 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads,

Albany, Auckland 1310, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in the United States of America by

Avon Books 1960

Published in Penguin Books 1992

eISBN 978-1-101-54877-6

Copyright © Jack Kerouac, 1960

All rights reserved

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

The scanning, uploading and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

PART ONE

Trembling and Chaste

I’M RIDING ALONG with Tristessa in the cab, drunk, with big bottle of Juarez Bourbon whiskey in the till-bag railroad lootbag they’d accused me of holding in railroad 1952—here I am in Mexico City, rainy Saturday night, mysteries, old dream sidestreets with no names reeling in, the little street where I’d walked through crowds of gloomy Hobo Indians wrapped in tragic shawls enough to make you cry and you thought you saw knives flashing beneath the folds—lugubrious dreams as tragic as the one of Old Railroad Night where my father sits big of thighs in smoking car of night, outside’s a brakeman with red light and white light, lumbering in the sad vast mist tracks of life—but now I’m up on that Vegetable plateau Mexico, the moon of Citlapol a few nights earlier I’d stumbled to on the sleepy roof on the way to the ancient dripping stone toilet—Tristessa is high, beautiful as ever, goin home gayly to go to bed and enjoy her morphine.

Night before I’ve in a quiet hassel in the rain sat with her darkly at Midnight counters eating bread and soup and drinking Delaware Punch, and I’d come out of that interview with a vision of Tristessa in my bed in my arms, the strangeness of her love-cheek, Azteca, Indian girl with mysterious lidded Billy Holliday eyes and spoke with great melancholic voice like Luise Rainer sadfaced Viennese actresses that made all Ukraine cry in 1910.

Gorgeous ripples of pear shape her skin to her cheek-bones, and long sad eyelids, and Virgin Mary resignation, and peachy coffee complexion and eyes of astonishing mystery with nothing-but-earth-depth expressionless half disdain and half mournful lamentation of pain. “I am seek,” she’s always saying to me and Bull at the pad—I’m in Mexico City wildhaired and mad riding in a cab down past the Ciné Mexico in rainy traffic jams, I’m swigging from the bottle, Tristessa is trying long harangues to explain that the night before when I put her in the cab the driver’d tried to make her and she hit him with her fist, news which the present driver receives without comment—We’re going down to Tristessa’s house to sit and get high—Tristessa has warned me that the house will be a mess because her sister is drunk and sick, and El Indio will be there standing majestically with morphine needle downward in the big brown arm, glitter-eyed looking right at you or expecting the prick of the needle to bring the wanted flame itself and going “Hm-za . . . the Aztec needle in my flesh of flame” looking all a whole lot like the big cat in Culiao who presented me the 0 the time I came down to Mexico to see other visions—My whiskey bottle has strange Mexican soft covercap that I keep worrying will slip off and all my bag be drowned in Bourbon 86 proof whiskey.

Through the crazy Saturday night drizzle streets like Hong Kong our cab pushes slowly through the Market ways and we come out on the whore street district and get off behind the fruity fruitstands and tortilla beans and taco

s shacks with fixed wood benches—It’s the poor district of Rome.

I pay the cab 3.33 by giving cabbie 10 pesos and asking “seis” for change, which I get without comment and wonder if Tristessa thinks I am too splurgy like big John Drunk in Mexico—But no time to think, we are hurrying through the slicky sidewalks of glisten-neon reflections and candle lights of little sidewalk sitters with walnuts on a towel for sale—turn quickly at the stinky alleyway of her tenement cell-house one story high—We go through dripping faucets and pails and boys and duck under wash and come to her iron door, which from adobe withins is unlocked and we step in the kitchen the rain still falling from the leaves and boards that served as the kitchen roof—allowing little drizzles to fizzle in the kitchen over the chicken garbage in the damp corner—Where, miraculously, now, I see the little pink cat taking a little pee on piles of okra and chickenfeed—The inside bedroom is littered completely and ransacked as by madmen with torn newspapers and the chicken’s pecking at the rice and the bits of sandwiches on the floor—On the bed lay Tristessa’s “sister” sick, wrapped in pink coverlet—it’s as tragic as the night Eddy was shot on the rainy Russia Street—

TRISTESSA IS SITTING on the edge of the bed adjusting her nylon stockings, she pulls them awkwardly from her shoes with big sad face overlooking her endeavors with pursy lips, I watch the way she twists her feet inward convulsively when she looks at her shoes.

She is such a beautiful girl, I wonder what all my friends would say back in New York and up in San Francisco, and what would happen down in Nola when you see her cutting down Canal Street in the hot sun and she has dark glasses and a lazy walk and keeps trying to tie her kimono to her thin overcoat as though the kimono was supposed to tie to the coat, tugging convulsively at it and goofing in the street saying “Here ees the cab—hey hees hey who—there you go—I breeng you back the moa-ny.” Money’s moany. She makes money sound like my old French Canadian Aunt in Lawrence “It’s not you moany, that I want, it’s you loave”—Love is loave. “Eets you lawv.” The law is lawv.—Same with Tristessa, she is so high all the time, and sick, shooting ten gramos of morphine per month,—staggering down the city streets yet so beautiful people keep turning and looking at her—Her eyes are radiant and shining and her cheek is wet from the mist and her Indian hair is black and cool and slick hangin in 2 pigtails behind with the roll-sod hairdo behind (the correct Cathedral Indian hairdo)—Her shoes she keeps looking at are brand new not scrawny, but she lets her nylons keep falling and keeps pulling on them and convulsively twisting her feet—You picture what a beautiful girl in New York, wearing a flowery wide skirt a la New Look with Dior flat bosomed pink cashmere sweater, and her lips and eyes do the same and do the rest. Here she is reduced to impoverished Indian Lady gloomclothes—You see the Indian ladies in the inscrutable dark of doorways, looking like holes in the wall not women—their clothes—and you look again and see the brave, the noble mujer, the mother, the woman, the Virgin Mary of Mexico.—Tristessa has a huge ikon in a corner of her bedroom.

It faces the room, back to the kitchen wall, in right hand corner as you face the woesome kitchen with its drizzle showering ineffably from the roof tree twigs and hammberboards (bombed out shelter roof)—Her ikon represents the Holy Mother staring out of her blue charaderees, her robes and Damema arrangements, at which El Indio prays devoutly when going out to get some junk. El Indio is a vendor of curios, allegedly,—I never see him on San Juan Letran selling crucifixes, I never see El Indio in the street, no Redondas, no anywhere—The Virgin Mary has a candle, a bunch of glass-fulla-wax economical burners that go for weeks on end, like Tibetan prayer-wheels the inexhaustible aid from our Amida—I smile to see this lovely ikon—

Around it are pictures of the dead—When Tristessa wants to say “dead” she clasps her hands in holy attitude, indicating her Aztecan belief in the holiness of death, by same token the holiness of the essence—So she has photo of dead Dave my old buddy of previous years now dead of high blood pressure at age 55—His vague Greek-Indian face looks out from pale indefinable photograph. I can’t see him in all that snow. He’s in heaven for sure, hands V-clasped in eternity ecstasy of Nirvana. That’s why Tristessa keeps clasping her hands and praying, saying, too, “I love Dave,” she had loved her former master—He had been an old man in love with a young girl. At 16 she was an addict. He took her off the street and, himself an addict of the street, redoubled his energies, finally made contact with wealthy junkies and showed her how to live—once a year together they’d taken hikes to Chalmas to the mountain to climb part of it on their knees to come to the shrine of piled crutches left there by pilgrims healed of disease, the thousand tapete-straws laid out in the mist where they sleep the night out in blankets and raincoats—returning, devout, hungry, healthy, to light new candles to the Mother and hitting the street again for their morphine—God knows where they got it.

I sit admiring that majestical mother of lovers.

THERE’S NO DESCRIBING the awfulness of that gloom in the holes in the ceiling, the brown halo of the night city lost in a green vegetable height above the Wheels of the Blakean adobe rooftops—Rain is blearing now on the green endlessness of the Valley Plain north of Actopan—pretty girls are dashing over gutters full of pools—Dogs bark at hirshing cars—The drizzle empties eerily into the kitchen’s stone Dank, and the door glistens (iron) all shiney and wet—The dog is howling in pain on the bed.—The dog is the little Chihuahua mother 12 inches long, with fine little feet with black toes and toenails, such a “fine” and delicate dog you couldnt touch her without she’d squeal in pain—“Y-e e e - p” All you could do was snap your finger gently at her and allow her to nip-nose her cold little wet snout (black as a bull’s) against your fingernails and thumb. Sweet little dog—Tristessa says she’s in heat and that’s why she cries—The rooster screams beneath the bed.

All this time the rooster’s been listening under the springs, meditating, turning to look all around in his quiet darkness, the noise of the golden humans above “Beu-veu-VAA?” he screams, he howls, he interrupts a half a dozen simultaneous conversations raging like torn paper above—The hen chuckles.

The hen is outside, wandering among our feet, pecking gently at the floor—She digs the people. She wants to come up near me and rub illimitably against my pant leg, but I dont give her encouragement, in fact havent noticed her yet and it’s like the dream of the vast mad father of the wild barn in howling Nova Scotia with the floodwaters of the sea about to engulf the town and surrounding pine countrysides in the endless north—It was Tristessa, Cruz on the bed, El Indio, the cock, the dove on the mantelpiece top (never a sound except occasional wing flap practice), the cat, the hen, and the bloody howling woman dog blacky Espana Chihuahua pooch bitch.

El Indio’s eyedropper is completely full, he jabs in the needle hard and it’s dull and it wont penetrate the skin and he jabs in harder and works it in but instead of wincing waits open mouthed with ecstasy and gets the dropful in, down, standing,—“You’ve got to do me a favor Mr. Gazookus,” says Old Bull Gaines interrupting my thought, “come down to Tristessa’s with me—I’ve run short—” but I’m bursting to explode out of sight of Mexico City with walking in the rain splashing through puddles not cursing nor interested but just trying to get home to bed, dead.

It’s the raving bloody book of dreams of the cursing world, full of suits, dishonesties and written agreements. And briberies, to children for their sweets, to children for their sweets. “Morphine is for pain,” I keep thinking, “and the rest is rest. It is what it is, I am what I am, Adoration to Tathagata, Sugata, Buddha, perfect in Wisdom and Compassion who has accomplished, and is accomplishing, and will accomplish, all these words of mystery.”

—Reason I bring the whiskey, to drink, to crash through the black curtain—At same time a comedian in the city in the night—Bepestered by glooms and lull intervenes, bored, drinking, curtsying, crashing, “Where I’m gonna do,”—

I pull the chair up to the corner of the foot of the bed so I can sit between the kitty and the Virgin Mary. The kitty, la gata in Spanish, the little Tathagata of the night, golden pink colored, 3 weeks old, crazy pink nose, crazy face, eyes of green, mustachio’d golden lion forceps and whiskers—I run my finger over her little skull and she pops up purring and the little purring-machine is started for awhile and she looks around the room glad watching what we’re all doing.—“She’s having golden thoughts,” I’m thinking.—Tristessa likes eggs otherwise she wouldnt allow a male rooster in this female establishment? How should I know how eggs are made. On my right the devotional candles flame before the clay wall.

IT’S INFINITELY WORSE than the sleeping dream I’ve had of Mexico City where I go dreary along empty white apartments, gray, alone, or where the marble steps of a hotel horrify me—It’s the rainy night in Mexico City and I’m in the middle of Mexico Thieves Market district and El Indio is a wellknown thief and even Tristessa was a pickpocket but I dont do more than flick my backhand against the bulge of my folded money sailorwise stowed in the railroad watchpocket of my jeans—And in shirt-pocket I have the travelers checks which are unstealable in a sense—That, Ah that side street where the gang of Mexicans stop me and rifle through my dufflebag and take what they want and take me along for a drink—It’s gloom as unpredicted on this earth, I realize all the uncountable manifestations the thinking-mind invents to place wall of horror before its pure perfect realization that there is no wall and no horror just Transcendental Empty Kissable Milk Light of Everlasting Eternity’s true and perfectly empty nature.—I know everything’s alright but I want proof and the Buddhas and the Virgin Marys are there reminding me of the solemn pledge of faith in this harsh and stupid earth where we rage our so-called lives in a sea of worry, meat for Chicagos of Graves—right this minute my very father and my very brother lie side by side in mud in the North and I’m supposed to be smarter than they are—being quick I am dead. I look up at the others glooping, they see I’ve been lost in thought in my corner chair but are pursuing endless wild worries (all mental 100%) of their own—They’re yakking in Spanish, I only understand snatches of that virile conversation—Tristessa keeps saying “chinga” at every other sentence, a swearing Marine,—she says it with scorn and her teeth bite and it makes me worry ‘Do you know women as well as you think you do?’—The rooster is unperturbed and lets go a blast.

Tristessa

Tristessa On the Road

On the Road The Dharma Bums

The Dharma Bums Maggie Cassidy

Maggie Cassidy Big Sur

Big Sur Dr. Sax

Dr. Sax Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46

Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46 The Sea Is My Brother

The Sea Is My Brother The Town and the City: A Novel

The Town and the City: A Novel Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Desolation Angels: A Novel

Desolation Angels: A Novel Book of Sketches

Book of Sketches Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha

Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha The Electrocution of Block 38383939383

The Electrocution of Block 38383939383 Haunted Life

Haunted Life Visions of Gerard

Visions of Gerard Orpheus Emerged

Orpheus Emerged Book of Blues

Book of Blues The Subterraneans

The Subterraneans The Haunted Life

The Haunted Life The Unknown Kerouac

The Unknown Kerouac The Town and the City

The Town and the City Visions of Cody

Visions of Cody Atop an Underwood

Atop an Underwood Lonesome Traveler

Lonesome Traveler Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg Vanity of Duluoz

Vanity of Duluoz Desolation Angels

Desolation Angels On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition)

On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition) The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel

The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel Wake Up

Wake Up The Poetry of Jack Kerouac

The Poetry of Jack Kerouac Doctor Sax

Doctor Sax