- Home

- Jack Kerouac

Vanity of Duluoz Page 10

Vanity of Duluoz Read online

Page 10

“‘Life is real, life is earnest,” I think your Wordsworth said.’

‘Guess what? My sister Stavroula has a new job, my brother Elia grew three inches this summer, my brother Pete is a sergeant in the Quartermaster Corps, my sister Sophia has a new boyfriend, my sister Xanthi got a new hand-knitted sweater from my sister-in-law, beautiful sweater, my father is well, my mother is making a big turkey today and gave me hell for coming to Hartford to you, and my brother Marty thinks of going in the service, and my brother Georgie is getting honors in high school, and my brother Chris is thinking of quitting the Lowell Sun and going in the service. Why dont you come back to Lowell and write sports for the Lowell Sun?’

‘I want to write “Atop an Underwood”. You ever hear about the old whore had a thousand spikes coming out of her like a porcupine: that’s how many stories I got coming out of my ears.’

‘But you’ve got to be selective.’

‘Where shall we eat?’

‘Let’s go to a sad lunchcart and have the blue plate turkey special and you bring pencil and paper and write a Saroyan story about it.’

‘Ah Sabby, you big old Sabby, I’m glad you come to see me on Thanksgiving Day . . .’

‘Something will come of it,’ says he almost crying. ‘Jacky you were s’posed to be a big football star and scholar of something or other at Columbia, what brings you to this sad room and with that sad typewriter, your tortured pillow, your hungers, your coveralls full of grease . . . are you really sure this is what you want to do?’

‘It’s not important, Sab, why didnt you bring me a cigar? It’s not important because I’m going to show you that I know what I’m doing. Parents come, parents go, schools come, schools go, but what’s an eager young soul going to do against the wall of what they call reality? Was Heaven based on the decisions of the aged fools? Did the elders tell the Lamb who to bless?’ — I didnt speak as well as that, of course, but it fits — ‘Whose eyes brood in the moot Yes? Who can tell the blooded Baron what’s to be done with farted America? When does youth take No for an answer? And what is youth? A rose, a swan, a ballet, a whale, a phosphorescent little fishy children’s crusade? A sumach growing by the tracks on the Boston & Maine? A tender white hand in the moonlight child? A loss of eleemosynary time? A crocka bullshit? When say the ancestors it’s time for Thanks Giving, and the turkey light is on the marsh, and the Indian corn you can smell, and the smoke, ah, Sabby, write me a poem.’

‘I happen to have one here; listen: “Remember, Jack, lest we / lose / Remember, Jack, sunsets / that glimmered on / two laughing, swimming / youths / Oh! so long ago / Remember the mists of / early New England / the sun glaring thru / the trees and chambers / of Beauty.” See? And then: “The dawn, the flowers you / brought home to your / mother and then back / back to realism” . . .’

Elated we ran out of the roominghouse and went down Main Street Hartford to a ‘sad lunchcart’ and had the blue plate turkey special. But by God and b’Jesus if we didnt part at the monument downtown, he to the right, me to the left, because we had different movies we wanted to see.

After the show, dusk lights, he met me again on the same corner. ‘How was the picture?’

‘Aoh, okay.’

‘I saw Victor Mature in I Wake Up Screaming.’

‘And?’

‘He’s very interesting: I dont care about the plot . . .’

‘Let’s go down and drink beer on Main Street . . .’

In there that night a guy tried to start a fight with my old Lowell buddy Joe Fortier now a grease monkey with me. I went into the men’s room, gave the men’s room door a coupla whacks with my fist, came out, went up to the guy, said ‘Leave Joe alone or I’ll knock you across the street’ and the guy left. Meanwhile Sabby was having a long talk at the bar with somebody. And two weeks later my father wrote and said ‘Come on back to New Haven, we’re packing and moving back to Lowell, I have a new job now in Lowell at Rolfe’s.’

Then, as now, I was proud that I had written something at least. A writer’s life is based on things like that. I wont bore the reader with the story of my writing development, can do that later, but this is the story of the techniques of suffering in the working world, which includes football and war.

Book Six

I

The most delicious truck ride I ever had in my life was when, after the movers put all the furniture aboard and my mother went ahead in a car with sister Nin, the movers arranged my father’s easy chair at the tailgate’s hem of the truck and I could sit there, lean back, smoke, sing, and watch the road wind away from me at 50 miles an hour, the line on curves snaking away into the woods of Connecticut, the woods getting different and more interesting the closer we approached old Lowell in north-eastern Massachusetts. And at dusk as we’re hitting thru Westford or thereabout and my old white birch reappeared grieving in hill silhouettes, tears came to my eyes to realize I was coming back home to old Lowell. It was November, it was cold, it was woodsmoke, it was swift waters in the wink of silver glare with its rose headband out yonder where Eve Star (some call it Venus, some call it Lucifer) stoppered up her drooling propensities and tried to contain itself in one delimited throb of boiling light.

Ah poetic. I keep saying ‘ah poetic’ because I didnt intend this to be a poetic paean of a book, in 1967 as I’m writing this what possible feeling can be left in me for an ‘America’ that has become such a potboiler of broken convictions, messes of rioting and fighting in streets, hoodlumism, cynical administration of cities and states, suits and neckties the only feasible subject, grandeur all gone into the mosaic mesh of Television (Mosaic indeed, with a capital M), where people screw their eyes at all those dots and pick out hallucinated images of their own contortion and are fed ACHTUNG! ATTENTION! ATENCIÓN! instead of Ah dreamy real wet lips beneath an old apple tree? Or that picture in Time Magazine a year ago showing a thousand cars parked in a redwood forest in California, all alongside similar tents with awnings and primus stoves, everybody dressed alike looking around everywhere at everybody with those curious new eyes of the second part of this century, only occasionally looking up at the trees and if so probably thinking ‘O how nice that redwood would look as my lawn furniture!’ Well, enough . . . for now.

Main thing is, coming home, ‘Farewell Song Sweet from My Trees’ of the previous August was washed away in November joys.

But it’s always been the case in my life that before a great catastrophe I feel unaccountably gloomy, lazy, sleepy, sick, depressed, black-souled and arm-hanged. That first week in Lowell, in a nice new clean little first floor of a two-family house on Crawford Street, after we’d unpacked and I stuck my old childhood desk near the window and the radiator, and sat there smoking on my pipe and writing a new Journal in ink, all I could do was gloom over the words and thoughts of Fyodor Dostoevsky. I happened to start up on him in one of his gloomiest works, Notes from the Underground. At midnight, in bright moonlight, I walked Moody Street over crunching snow and felt something awful that had not been in Lowell before. For one thing I was the ‘failure back in town’, for another I had lost the glamor of New York City and the Columbia campus and the tweeded outlook of sophomores, had lost glittering Manhattan, was back trudging among the brick walls of the mills. My Pa slept next to me in his twin bed snoring like a booming wind. Ma and Nin slept together in the double bed. The parlor, with its old stuffed furniture and old squareback piano, was locked for the winter. And I had to find a job.

Then one Sunday night I came walking out of the Royal Theater all elated because I had just seen Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane and by God, what a picture! I wanted to be a genius of poetry in film like Welles. I was rushing home to figure out a movie play. It was snowing and cold, I heard a little boy rush up with newspapers yelling: ‘Japs bomb Pearl Harbor!’ ‘War declared on Japan and Germany!’ the next day. It’s as tho I’d felt it coming, just as, years

later, the night before the death of my father, I had tried, or would try, to walk around the block and only ended up shuffling head down . . . more on that near the end of this.

All I was supposed to do was wait for the Navy V-2 program to call me up for an examination into whether I should be in the Naval Air Force. So, meanwhile to get that job, I went to the Lowell Sun and asked to see the owner of the newspaper, Jim Mayo, to see whether I could be hired as a trucker’s helper delivering piles of newspapers to the dealers. He said ‘Arent you the Jack Duluoz who was a football star a few years ago in Lowell High? And in New York, at Yale, it was?’

‘Columbia.’

‘And you were preparing for journalism? Why should you be a delivery boy? Here, you take this note to go into the sports desk and tell them I want you start right in Monday morning as a sports reporter. What the heck, boy!’ — clap on the back — ‘We’re not all hicks around here. Fifteen dollars a week do okay as a starter.’

He didnt ask, in those days employers didnt ask, but I thrilled temporarily at the thought of whipping out my college sports coat and pants and regaining ye old necktie glamor at a desk in the bright morning of men and business things.

II

So thru January and February I was a sports writing cub for the Lowell Sun. My Pa was very proud. In fact, on several occasions he got a day’s work running a linotype in the press room and I used to proudly bring him one of my typewritten stories (say about Lowell High basketball) and give it to him on his rack, and we’d smile. ‘Stick to it kid, decouragez ons nous pas, ça va venir, ça va venir’ (Means: ‘Let’s not get discouraged, it’s gonna come, it’s gonna come.’)

It was at this time that the phrase ‘Vanity of Duluoz’ occurred to me and was made the title of a novel that I began writing at my sports desk at about noon every day, because from nine till noon was all it took me to do my whole day’s work. I could write fast and type fast and just kept feeding that copy all over the place on fast feet. Noon, when everybody left the tacking editorial office, and I was alone, I snuck out the pages of my secret novel and continued writing it. It was the greatest fun I ever had ‘writing’ in my life because I had just discovered James Joyce and I was imitating Ulysses I thought (really imitating ‘Stephen Hero’ I later discovered, a real adolescent but sincere effort, with ‘power’ and ‘promise’ pronounced Arch MacDougald our local cultural mentor later). I had discovered James Joyce, the stream of consciousness, I have that whole novel right in front of me now. It was simply the day-by-day doings of nothing in particular by ‘Bob’ (me), Pater (my Pa), etc., etc., all the other sportswriters, all my buddies down at the theater and in the saloons at night, all the studies I had rebegun in the Lowell Public Library (on a grand scale), my afternoons of exercising in the YMCA, the girls I went out with, the movies I saw, my talks with Sabbas, with my mother and sister, an attempt to delineate all of Lowell as Joyce had done for Dublin.

Just for instance the first page went like this: ‘Bob Duluoz awoke neatly, surprised at himself, swung his legs deftly from under the warm sheets. Two weeks now, doing this daily, how the hell? myself one of Earth’s biggest slothards. Rose in the cold gray morning without a tremor.

“In the kitchen gruntled Pater.

“‘Hurry up there, it’s past nine o’clock.”

‘Duluoz, the crazy bastard. He sat down on the bed and thought for just a moment. How do I do it? Bleary eyes.

‘Morning in America.

“‘What time does the mail come?” ask gruntled Pater.

‘Duluoz, the turd said: “Around nine o’clock.” Oooooaayaawn. He fetched up his white socks, which were none too white. He put them on. Shoes need a shine. Old socks found dusting slowly under dresser; use them. He rubbed his shoes shinewise with the old socks. Then on swung the trousers, jingling, jingling, jingling. Jingle. Chain and some money and two keys, one for home, one for Business Men’s Lockers in local YMCA. Local . . . that son of a bitch of a newspaper world. Free $21 membership . . . showers, rower, basketballs, track pool, etc., radio too. Handle I the destiny of the ‘Y’s’ press success. Handle I the. Press success. Bob Duluoz, the rovin reporter. What Socko calls him.

‘Morning in America.’

(And so on.)

Get it?

That’s how writers begin, by imitating the masters (without suffering like said masters), till they larn their own style, and by the time they larn their own style there’s no more fun in it, because you cant imitate any other master’s suffering but your own.

Most beautiful of all in those winter nights I used to leave my father snoring in his room, sneak into the kitchen, turn on the light, brew a pot of tea, put my feet in the oil stove oven, lean back that way in the rocking chair, and read the Book of Job down to its tiniest detail in its entirety, and Goethe’s Faust, and Joyce’s Ulysses, till daybreak. Sleep two hours and go to the Lowell Sun. Finish the newspaper work at noon, write a chapter of the ‘novel’. Go eat two hamburgs on Kearney Square in White Tower. Walk up to the Y, exercise, even punch the sandbag and run the 300 around the upstairs track fairly fast. Then into the library with notebook where I was reading H. G. Wells and taking down elaborate notes, right from the beginning with the Mesozoic age of reptiles, intending to work my way up to Alexander the Great before spring and actually looking up all of Wells’ references that puzzled or interested me in the Encyclopaedia Britannica XI Ed. which was right there in my old rotunda shelves. ‘By the time I’m done,’ I was vowing, ‘I shall know everything that ever happened on earth in detail.’ Not only that, but home at dusk, supper, an argument with Pa at supper table, a nap, and back to the library for a second round of ‘learning everything on earth’. At nine, library closing, exhausted from this horrible schedule, old sad Sabbas was always waiting for me at the door of the library, with that melancholy smile, ready for a hot fudge sundae or a beer, anything so long as he could exchange with me some kind of bouquet of homage.

This isnt a book about Sabby proper, so I hurry along . . .

III

And who to this day can give a flinging frig for what Superintendent Orrenberger said, places that are called The Commonwealth, like Massachusetts, are usually the nesting holes of thieves.

Because, as I say Sabby and my folks aside, when winds of March began to melt the porcelain of that old winter, I got it in my head that I wanted to quit that newspaper and hit the road and go South. It’s a good thing Jeb Stuart never met me in 1862, we woulda been a great team of hellions. I love the South, I dont know why, it’s the people, the courtliness, the care about your own courtliness, the disregard of your beau regard, the love of tit for tat in a real field instead of deception, the language above all: ‘Boy Ah’m a-gonna tell you naow, I’m going South.’ One afternoon the Lowell Sun assigned me to go interview Coach Yard Parnell of the Lowell Textile Institute baseball team and instead, when I came home to get ready for this interview, just a few blocks away, I just sat in my room and stared at the wall and fluffed off and said ‘Ah hell, shuck, I’m not going anywhere to interview nobody.’ They called, I didnt answer the phone. I just stayed home and stared at the wall. Already Moe Cole’d been over a coupla times on the couch in everybody-working-afternoon. If Ariadne was mounted by a Ram, or wanted to mount a Ram, what difference does it make to a nineteen-year-old boy?

I am the descendant of Jean-Baptiste LeBri de Duluoz an old gaffer carpenter from St-Hubert in Temiscouata County, Quebec, who built his own house in Nashua N.H. and used to curse at God swinging his kerosene lamp during thunderstorms yelling ‘Varge! [Whack!] Frappe! [Hit!] Vas y! [Go ahead!]’ and ‘Dont give me no back talk’ and when women hit up on him in the street he told them where to get off with their bustles and bounces and desires for bracelets, he did. The Duluoz family has always been enraged. Is that a sign of bad blood? The father line of Duluoz, it isnt French, it’s Cornish, it’s Cornish Celtic (the name of the languag

e is Kernuak), and they’re always enraged and arguing about something, there is in them, not the ‘angry young man’ but the ‘infuriated old man’ of the sea. My father that night is saying: ‘Did you go to Textile Institute and interview the baseball coach?’

‘No.’

‘Why not?’ No answer. ‘Did that Mike Hennessey have to say anything in his letter from New York about Lu Libble wants you to come back to the team?’

‘All kinds of things, he’s thinking of joining the Naval Reserve, he says there is a course for sophomores so I guess I might make that.’ But Pa’s face (Pater’s face) said something sarcastic; and I say ‘What’s the face for? You dont think I’ll ever get back to college, do you? You dont ever think I can do anything.’

Ma sighed. ‘There they go again.’

‘I didnt say that!’ shouted Pa angrily. ‘But they wont be too glad to have you after the way you let them down last fall . . .’

‘I left because I wanted to help the family, that was one reason, there were many reasons . . . such as I shouldnt draw breath to explain to an old pain in the ass even if it were you yourself, ee bejesus and be goddam, I was sick of the coach, he was all over me, I was sick, I knew the war was coming, I got the hell out. I wanted to stay out for awhile and study America.’

‘Study mongrel America? And the gradual Pew York? Do you think you can do what you feel like all your life?’

‘Yes.’

He laughed: ‘Poor kid, ha ha ha, you dont even know what you’re up against, and the trouble with us Duluozes is that we’re Bretons and Cornishmen and it’s that we cant get along with people, maybe we were descended from pirates, or cowards, who knows, because we cant stand rats, that coach was a rat. You shoulda socked him on the banana nose instead of sneaking out like a coward.’

‘O sure, suppose I woulda socked him . . . would I be getting back there?’

Tristessa

Tristessa On the Road

On the Road The Dharma Bums

The Dharma Bums Maggie Cassidy

Maggie Cassidy Big Sur

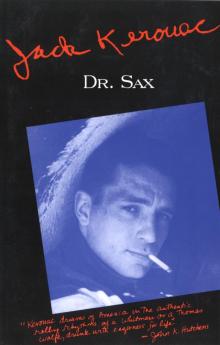

Big Sur Dr. Sax

Dr. Sax Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46

Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46 The Sea Is My Brother

The Sea Is My Brother The Town and the City: A Novel

The Town and the City: A Novel Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Desolation Angels: A Novel

Desolation Angels: A Novel Book of Sketches

Book of Sketches Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha

Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha The Electrocution of Block 38383939383

The Electrocution of Block 38383939383 Haunted Life

Haunted Life Visions of Gerard

Visions of Gerard Orpheus Emerged

Orpheus Emerged Book of Blues

Book of Blues The Subterraneans

The Subterraneans The Haunted Life

The Haunted Life The Unknown Kerouac

The Unknown Kerouac The Town and the City

The Town and the City Visions of Cody

Visions of Cody Atop an Underwood

Atop an Underwood Lonesome Traveler

Lonesome Traveler Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg Vanity of Duluoz

Vanity of Duluoz Desolation Angels

Desolation Angels On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition)

On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition) The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel

The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel Wake Up

Wake Up The Poetry of Jack Kerouac

The Poetry of Jack Kerouac Doctor Sax

Doctor Sax