- Home

- Jack Kerouac

Big Sur Page 13

Big Sur Read online

Page 13

28

STRANGE—and Perry Yturbide that first day while Billie’s at work and we’ve just called his mother now wants me to come with him to visit a general of the U.S. Army—“Why? and what’s all these generals looking out of silent windows?” I say—But nothing surprises Perry—“Well go there because I want you to dig the most beautiful girls we ever saw,” in fact we take a cab—But the “beautiful girls” turn out to be 8 and 9 and 10 years old, daughters of the general or maybe even cousins or daughters of a nextdoor strange general, but the mother is there, there are also boys playing in a backroom, we have Elliott with us whom Perry has carried on his shoulders all the way—I look at Perry and he says “I wanted you to see the most beautiful little cans in town” and I realize he’s dangerously insane—In fact he then says “See this perfect beauty?” a pony tailed 10 year old daughter of the general (who aint home yet) “I’m going to kidnap her right now” and he takes her by the hand and they go out on the street for an hour while I sit there over drinks talking to the mother—There’s some vast conspiracy to make me go mad anyway—The mother is polite as ordinarily—The general comes home and he’s a rugged big baldheaded general and with him is his best friend a photographer called Shea, a thin well combed welldressed ordinary downtown commercial photographer of the city—I dont understand anything—But suddenly little Elliott is crying in the other room and I rush in there and see that the two boys have whacked him or something because he did something wrong so I chastise them and carry Elliott back into the livingroom on my shoulders like Perry does, only Elliott wants to get down off my shoulders at once, in fact he wont even sit on my lap, in fact he hates my guts—I call Billie desperately at her agency and she says she’ll be over to pick us all up and adds “How’s Perry today?”—“He’s kidnapping little girls he says are beautiful, he wants to marry 10 year old girls with pony tails”—“That’s the way he is, be sure to dig him”—In her musical sad voice over the phone.

I turn my poor tortured attention to the general who says he was an anti-Fascist fighter with the Maquis during World War II and also a guerilla in the South Pacific and knows one of the finest restaurants in San Francisco where we can all go feast, a Fillipino restaurant near Chinatown, I say okay, great—He gives me more booze—Seeing the amusing Irish face of Shea the photographer I yell “You can take my picture anytime you want” and he says sinister: “Not for propaganda reasons, anything but propaganda reasons”—“What the hell do you mean propaganda reasons, I aint got nothin to do with propaganda” (and here comes Perry back through the door with Poopoo holding his hand, they’ve gone to dig the street and have a coke) and I realize everybody is just living their lives quietly but it’s only me that’s insane.

In fact I yearn to have old Cody around to explain all this to me tho it soon becomes apparent to me not even Cody could explain, I’m beginning to go seriously crazy, just like Subterranean Irene went crazy tho I dont realize it yet—I’m beginning to read plots into every simple line—Besides the “general” scares me even further by turning out to be a strange affluent welldressed civilian who doesnt even help me to pay the tab for the Fillipino dinner which we have, meeting Billie at the restaurant, and the restaurant itself is weird especially because of a big raunchy mad thicklipped sloppy young Fillipino woman sitting alone at the end of the restaurant gobbling up her food obscenely and looking at us insolently as tho to say “Fuck you, I eat the way I like” splashing gravy everywhere—I cant understand what’s going on—Because also the general has suggested this dinner but I have to pay for everybody, him, Shea, Perry, Billie, Elliott, me, others, strange apocalyptic madness is now shuddering in my eyeballs and I’m even running out of money in their Apocalypse which they themselves have created in this San Francisco silence anyway.

I yearn to go hide and cry in Evelyn’s arms but I end up hiding in Billie’s arms and here she goes again, the second evening, explaining all her spiritual ideas—“But what about Perry? what’s he up to? and who’s that strange general? what are you, a bunch of communists?”

29

THE LITTLE CHILD REFUSES TO SLEEP in his crib but has to come trotting out and watch us make love on the bed but Billie says “That’s good, he’ll learn, what other way will he ever learn?”—I feel ashamed but because Billie is there and she’s the mother I must go along and not worry—Another sinister fact—At one point the poor child is drooling long slavers of spit from his lips watching, I cry “Billie, look at him, it’s not good for him” but she says again “Anything he wants he can have, even us.”

“But kid it’s not fair, why doesn’t he just sleep?”—“He doesnt wanta sleep, he wants to be with us”—“Ooh,” and I realize Billie is insane and I’m not as insane as I thought and there’s something wrong—I feel my self skidding: also because during the following week I keep sitting in that same chair by the goldfish bowl drinking bottle after bottle of port like an automaton, worrying about something, Monsanto comes to visit, McLear, Fagan, everybody, they call to me dashing up the stairs and we have long drunken days talking but I never seem to get out of that chair and never even take another delightful warm bath reading books—And at night Billie comes home and we pitch into love again like monsters who dont know what else to do and by now I’m too blurry to know what’s going on anyway tho she reassures me everything is alright, and meanwhile Cody has completely disappeared—In fact I call him up and say “Are you gonna come back and get me here?”—“Yes yes yes in a few days, stay there” as tho maybe he wants me to learn what’s happening like putting me through an ordeal to see what I have to say about it because he’s been through the ordeal himself.

In fact everything is going crazy.

Perry’s visits scare me: I begin to think he must be one of those “strong armers” who beat up old men: I watch him warily—All this time he’s pacing back and forth saying “Man dont you appreciate those sweet little cans? what does it matter how old a woman is, 9 or 19, those little pony tails jiggling as they walk with those little jigglin cans”—“Did you ever kidnap one?”—“You out of wine, I’ll make a run for you get some more, or would you rather have pot or sumptin? what’s wrong with you?”—“I dont know what’s goin on!”—“You’re drinking too much maybe, Cody told me you’re falling apart man, dont do it”—“But what’s goin on?”—“Who cares, pops, we’re all swingin in love and tryin to go from day to day with self respect while all the squares are puttin us down”—“Who?”—“The Squares, puttin down Us . . . we wanta swing and live and carry across the night like when we get to L.A. I’m goin to show you the maddest scene some friends of mine down there” (in my drunkenness I’ve already projected a big trip with Billie and Elliott and Perry to Mexico but we’re going to stop in L.A. to see a rich woman Perry knows who’s going to give him money and if she doesnt he’s going to get it anyway, and as I say Billie and I are going to get married too)—The insanest week of my life—Billie at night saying “You’re worried that I cant handle marrying you but of course we can, Cody wants it too, I’ll talk to your mother and make her love me and need me: Jack!” she suddenly cries with anguished musical voice (because I’ve just said “Ah Billie go get yourself a he-man and get married”), “You’re my last chance to marry a He Man”—“Whattayou mean He Man, dont you realize I’m crazy?”—“You’re crazy but you’re my last chance to have an understanding with a He Man”—“What about Cody?”—“Cody will never leave Evelyn”—Very strange—But more, tho I dont understand it.

30

I DO UNDERSTAND THE STRANGE DAY BEN FAGAN FINALLY CAME to visit me alone, bringing wine, smoking his pipe, and saying “Jack you need some sleep, that chair you say you’ve been sitting in for days have you noticed the bottom is falling out of it?”—I get on the floor and by God look and it’s true, the springs are coming out—“How long have you been sitting in that chair?”—“Every day waiting for Billie to come home and talking to Perry and the others all

day. . . My God let’s go out and sit in the park,” I add—In the blur of days McLear has also been over on a forgotten day when, on nothing but his chance mention that maybe I could get his book published in Paris I jump up and dial longdistance for Paris and call Claude Gallimard and only get his butler apparently in some Parisian suburb and I hear the insane giggle on the other end of the line—“Is this the home, c’est le chez eux de Monsieur Gallimard?”—Giggle—“Où est Monsieur Gallimard?”—Giggle—A very strange phone call—McLear waiting there expectantly to get his “Dark Brown” published—So in a fury of madness I then call London to talk to my old buddy Lionel just for no reason at all and I finally reach him at home he’s saying on the wire “You’re calling me from San Francisco? buy why?”—Which I cant answer any more than the giggling butler (and to add to my madness, of course, why should a longdistance call to Paris to a publisher end up with a giggle and a longdistance call to an old friend in London end up with the friend getting mad?)—So Fagan now sees I’m going overboard crazy and I need sleep—“We’ll get a bottle!” I yell—But end up, he’s sitting in the grass of the park smoking his pipe, from noon to 6 P.M., and I’m passed out exhausted sleeping in the grass, bottle unopened, only to wake up once in a while wondering where I am and by God I’m in Heaven with Ben Fagan watching over men and me.

And I say to Ben when I wake up in the gathering 6 P.M. dusk “Ah Ben I’m sorry I ruined our day by sleeping like this” but he says: “You needed the sleep, I told ya”—“And you mean to tell me you been sitting all afternoon like that?”—“Watching unexpected events,” says he, “like there seems to be sound of a Bacchanal in those bushes over there” and I look and hear children yelling and screaming in hidden bushes in the park—“What they doing?”—“I dont know: also a lot of strange people went by”—“How long have I been sleeping?”—“Ages”—“I’m sorry”—“Why should be sorry, I love you anyway”—“Was I snoring?”—“You’ve been snoring all day and I’ve been sitting here all day”—“What a beautiful day!”—“Yes it’s been a beautiful day”—“How strange!”—“Yes, strange . . . but not so strange either, you’re just tired”—“What do you think of Billie?”—He chuckles over his pipe: “What do you expect me to say? that the frog bit your leg?”—“Why do you have a diamond in your forehead?”—“I dont have a diamond in my forehead damn you and stop making arbitrary conceptions!” he roars—“But what am I doing?”—“Stop thinking about yourself, will ya, just float with the world”—“Did the world float by the park?”—“All day, you should have seen it, I’ve smoked a whole package of Edgewood, it’s been a very strange day”—“Are you sad I didnt talk to you?”—“Not at all, in fact I’m glad: we better be starting back,” he adds, “Billie be coming home from work soon now”—“Ah Ben, Ah Sunflower”—“Ah shit” he says—“It’s strange”—“Who said it wasnt”—“I dont understand it”—“Dont worry about it”—“Hmm holy room, sad room, life is a sad room”—“All sentient beings realize that,” he says sternly—Benjamin my real Zen Master even more than all our Georges and Arthurs actually—“Ben I think I’m going crazy”—“You said that to me in 1955”—“Yeh but my brain’s gettin soft from drinkin and drinkin and drinkin”—“What you need is a cup of tea I’d say if I didnt know that you’re too crazy to know how really crazy you are”—“But why? what’s going on?”—“Did you come three thousand miles to find out?”—“Three thousand miles from where, after all? from whiney old me”—“That’s alright, everything is possible, even Nietzsche knew that”—“Aint nothin wrong with old Nietzsche”—“’Xcept he went mad too”—“Do you think I’m going mad?”—“Ho ho ho” (hearty laugh)—“What’s that mean, laughing at me?”—“Nobody’s laughing at you, dont get excited”—“What’ll we do now?”—“Let’s go visit the museum over there”—There’s a museum of some sort across the grass of the park so I get up wobbly and walk with old Ben across the sad grass, at one point I put my arm over his shoulder and lean on him—“Are you a ghoul?” I ask—“Sure, why not?”—“I like ghouls that let me sleep?”—“Duluoz it’s good for you to drink in a way ’cause you’re awful stingy with yourself when You’re sober”—“You sound like Julien”—“I never met Julien but I understand Billie looks like him, you kept saying that before you went to sleep”—“What happened while I was asleep?”—“Oh, people went by and came back and forth and the sun sank and finally sank down and’s gone now almost as you can see, what you want, just name it you got it”—“Well I want sweet salvation”—“What’s sposed to be sweet about salvation? maybe it’s sour”—“It’s sour in my mouth”—“Maybe your mouth is too big, or too small, salvation is for little kitties but only for awhile”—“Did you see any little kitties today?”—“Shore, hundreds of em came to visit you while you were sleeping”—“Really?”—“Sure, didnt you know you were saved?”—“Now come on!”—“One of them was real big and roared like a lion but he had a big wet snout and kissed you and you said Ah”—“What’s this museum up here?”—“Let’s go in and find out”—That’s the way Ben is, he doesnt know what’s going on either but at least he waits to find out maybe—But the museum is closed—We stand there on the steps looking at the closed door—“Hey,” I say, “the temple is closed.”

So suddenly in red sundown me and Ben Fagan arm in arm are walking slowly sadly back down the broad steps like two monks going down the esplanade of Kyoto (as I imagine Kyoto somehow) and we’re both smiling happily suddenly—I feel good because I’ve had my sleep but mainly I feel good because somehow old Ben (my age) has blessed me by sitting over my sleep all day and now with these few silly words—Arm in arm we slowly descend the steps without a word—It’s been the only peaceful day I’ve had in California, in fact, except alone in the woods, which I tell him and says “Well, who said you werent alone now?” making me realize the ghostliness of existence tho I feel his big bulging body with my hands and say: “You sure some pathetic ghost with all that ephemeral heavy crock a flesh”—“I didnt say nottin” he laughs—“Whatever I say Ben, dont mind it, I’m just a fool”—“You said in 1957 in the grass drunk on whiskey you were the greatest thinker in the world”—“That was before I fell asleep and woke up: now I realize I’m no good at all and that makes me feel free”—“You’re not even free being no good, you better stop thinking, that’s all”—“I’m glad you visited me today, I think I might have died”—“It’s all your fault”—“What are we gonna do with our lives?”—“Oh,” he says, “I dunno, just watch em I guess”—“Do you hate me? . . . well, do you like me? . . . well, how are things?”—“The hicks are alright”—“Anybody hex ya lately . . . ?”—“Yeh, with cardboard games?”—“Cardboard games?” I ask—“Well you know, they build cardboard houses and put people in them and the people are cardboard and the magician makes the dead body twitch and they bring water to the moon, and the moon has a strange ear, and all that, so I’m alright, Goof.”

“Okay.”

31

SO THERE I AM AS IT STARTS TO GET DARK standing with one hand on the window curtain looking down on the street as Ben Fagan walks away to get the bus on the corner, his big baggy corduroy pants and simple blue Goodwill workshirt, going home to the bubble bath and a famous poem, not really worried or at least not worried about what I’m worried about tho he too carries that anguishing guilt I guess and hopeless remorse that the potboiler of time hasnt made his early primordial dawns over the pines of Oregon come true—I’m clutching at the drapes of the window like the Phantom of the Opera behind the masque, waiting for Billie to come home and remembering how I used to stand by the windows like this in my childhood and look out on dusky streets and think how awful I was in this development everybody said was supposed to be “my life” and “their lives.”—Not so much that I’m a drunkard that I feel guilty about but that others who occupy this plane of “life on earth” with me dont feel guilty at all—Crooked judges shaving and smiling in the morning on the w

ay to their heinous indifferences, respectable generals ordering soldiers by telephone to go die or drop dead, pickpockets nodding in cells saying “I never hurt anybody,” “that’s one thing you can say for me, yes sir,” women who regard themselves saviors of men simply stealing their substance because they think their swan-rich necks deserve it anyway (though for every swan-rich neck you lose there’s another ten waiting, each one ready to lay for a lemon), in fact awful hugefaced monsters of men just because their shirts are clean deigning to control the lives of working men by running for Governor saying “Your tax money in my hands will be aptly used,” “You should realize how valuable I am and how much you need me, without me what would you be, not led at all?”—Forward to the big designed mankind cartoon of a man standing facing the rising sun with strong shoulders with a plough at his feet, the necktied governor is going to make hay while the sun rises—?—I feel guilty for being a member of the human race—Drunkard yes and one of the worst fools on earth—In fact not even a genuine drunkard just a fool—But I stand there with hand on curtain looking down for Billie, who’s late, Ah me, I remember that frightening thing Milarepa said which is other than those reassuring words of his I remembered in the cabin of sweet loneness on Big Sur: “When the various experiences come to light in meditation, do not be proud and anxious to tell other people, else to Goddesses and Mothers you will bring annoyance” and here I am a perfectly obvious fool American writer doing just that not only for a living (which I was always able to glean anyway from railroad and ship and lifting boards and sacks with humble hand) but because if I dont write what actually I see happening in this unhappy globe which is rounded by the contours of my deathskull I think I’ll have been sent on earth by poor God for nothing—Tho being a Phantom of the Opera why should that worry me?—In my youth leaning my brow hopelessly on the typewriter bar, wondering why God ever was anyway?—Or biting my lip in brown glooms in the parlor chair in which my father’s died and we’ve all died a million deaths—Only Fagan can understand and now he’s got his bus—And when Billie comes home with Elliott I smile and sit down in the chair and it utterly collapses under me, blang, I’m sprawled on the floor with surprise, the chair has gone.

Tristessa

Tristessa On the Road

On the Road The Dharma Bums

The Dharma Bums Maggie Cassidy

Maggie Cassidy Big Sur

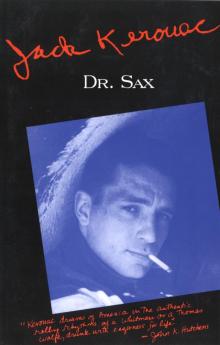

Big Sur Dr. Sax

Dr. Sax Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46

Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46 The Sea Is My Brother

The Sea Is My Brother The Town and the City: A Novel

The Town and the City: A Novel Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Desolation Angels: A Novel

Desolation Angels: A Novel Book of Sketches

Book of Sketches Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha

Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha The Electrocution of Block 38383939383

The Electrocution of Block 38383939383 Haunted Life

Haunted Life Visions of Gerard

Visions of Gerard Orpheus Emerged

Orpheus Emerged Book of Blues

Book of Blues The Subterraneans

The Subterraneans The Haunted Life

The Haunted Life The Unknown Kerouac

The Unknown Kerouac The Town and the City

The Town and the City Visions of Cody

Visions of Cody Atop an Underwood

Atop an Underwood Lonesome Traveler

Lonesome Traveler Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg Vanity of Duluoz

Vanity of Duluoz Desolation Angels

Desolation Angels On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition)

On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition) The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel

The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel Wake Up

Wake Up The Poetry of Jack Kerouac

The Poetry of Jack Kerouac Doctor Sax

Doctor Sax