- Home

- Jack Kerouac

On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition) Page 2

On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition) Read online

Page 2

John Clellon Holmes astutely noted that the “the breakup of [Kerouac’s] Lowell-home, the chaos of the war years and the death of his father, had left him disrupted, anchorless, a deeply traditional nature thrown out of kilter, and thus enormously sensitive to anything uprooted, bereft, helpless or persevering.” To Kerouac, this personal sense of loss and restlessness recorded in The Town and the City led to faith in the possibilities of movement, and to a connection with the historic aspirational American belief in movement as the means of self-transformation. From Whitman’s Song of the Open Road to Cormac McCarthy’s bleakly radiant postapocalyptic novel The Road (2006), the road narrative has always been central to America’s cultural representations of itself. When in a 1949 notebook Kerouac described his decision to set his second novel on the road, he said it was “like a message from God giving a sure direction.”

The road would occupy Kerouac from the beginning to the end of his writing life. In 1940 he wrote a four-page short story called “Where the Road Begins” that explored the contending attractions of the open road and the joy of returning home again. The Town and the City is in part a road narrative, as Joe Martin, intoxicated by the perfume of spring flowers and “the sharp pungent smell of exhaust fumes on the highway, and the heat of the highway itself cooling under the stars,” and embodying and anticipating a new American generation’s questing need to go, feels himself fated and driven to take a “wild wonderful trip out West, anywhere, everywhere.” In the month of his death Kerouac submitted reworked and previously discarded material from On the Road to his agent Sterling Lord as the novel Pic (posthumously published in 1971).

As Holmes writes, Kerouac, as Americans always have, “hankered for the West, for Western health and openness of spirit, for the immemorial dream of freedom [and] joy.” The on-the-move outsider nation of On the Road dramatizes Kerouac’s strong belief that this elemental American idealism, this faith in a place at the end of the road where you could make both a home and a stand had, in Holmes’s words, “been outlawed to the margins of American life in his time. His most persistent desire in those days was to chronicle what was happening on those margins.”

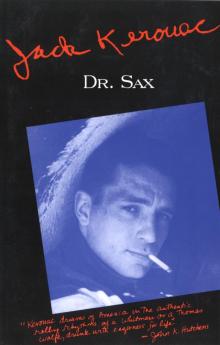

Kerouac writes from those margins. The love of America that so distinguishes On the Road and Visions of Cody came from Kerouac’s own double sense of himself as both American and French Canadian. This idea of Kerouac as a postcolonial writer is confirmed most particuarly by his magic-realist novel Doctor Sax, in which Kerouac writes the French-Canadian experience into the American national narrative in a way similar to Salman Rushdie’s inscription of the Anglo-Indian experience in Midnight’s Children. Interestingly, Kerouac was working on both Road and Sax at the same time and considered merging the two novels. As late as the summer of 1950 he was using a French-Canadian narrator for Road, but only traces remain of Sax in that novel.

More than anything else the story of On the Road returns again and again to Neal Cassady. Cassady was Kerouac’s lost brother returned; the longed-for adventuring Western hero made young again; and the living expression of the Dionysian side of Kerouac’s own dual nature. Cassady, as Kerouac would write in Visions of Cody, was the one “who watched the sun go down, at the rail, by my side, smiling,” but he was also a destructive presence from whose speed-freak con-man mystique Kerouac sometimes felt the need to escape. They met in 1947 but did not ride together until December of 1948, and with each new adventure Kerouac steered the novel further toward him. He was variously named Vern Pomery Jr., Dean Pomery Jr., Dean Pomeray Jr., Neal Cassady, Dean Moriarty, and in Visions of Cody, Cody Pomeray. In the scroll Kerouac makes the connection explicit:

My interest in Neal is the interest I might have had in my brother that died when I was five years old to be utterly straight about it. We have a lot of fun together and our lives are fuckt up and so there it stands. Do you know how many states we’ve been in together?

Kerouac and Cassady made two trips in late December with LuAnne Henderson and Al Hinkle, shuttling family belongings from Rocky Mount, North Carolina (where Kerouac was spending Christmas with his family), to the Kerouac home in Ozone Park, New York. After New Year’s celebrations in New York the four drove to Algiers, Louisiana, to visit Bill Burroughs and his family. Herbert Huncke and Hinkle’s new wife Helen were also staying in Burroughs’s ramshackle house by the bayou. Leaving Hinkle in Louisiana with Helen, Cassady, LuAnne, and Kerouac then proceeded to San Francisco. Kerouac returned to New York alone in February.

On March 29, 1949, Kerouac learned that Harcourt, Brace had accepted The Town and the City. A jubilant Kerouac continued work on On the Road, filling notebook pages with plans and writing to Alan Harrington on April 23 “I start work in earnest on my second novel this week.” Kerouac reports the arrests in New Orleans of Bill Burroughs for drug and weapons possession, and in New York of Allen Ginsberg, Herbert Huncke, Vicki Russell, and Little Jack Melody after the police raided Ginsberg’s apartment and found drugs and stolen goods. The arrest of his friends, the fear that he might be questioned himself, and the acceptance of his novel led Kerouac to write that he was at a turning point in his life, “the end of my ‘youth.’” Kerouac was “determined to start a new life.” In this new version of the novel there would be “no more” Ray Smith. Instead, Red Moultrie, a merchant seaman imprisoned in New York on drugs charges, will look for God, family, and home in the West.

In May, Kerouac traveled to Denver as a soon-to-be-published young novelist with a thousand-dollar advance. Hitchhiking to save money, Kerouac was “itching” to establish the family home he had dreamed about for years. On a late-May Sunday afternoon Kerouac writes that starting “‘On the Road’ back in Ozone, and here, is difficult. I wrote one full year before starting T & C, (1946)—but this mustn’t happen again. Writing is my work…so I’ve got to move.” On June 2 Kerouac’s mother Gabrielle, his sister Caroline and brother-in-law Paul Blake, and their son Paul Jr. joined Kerouac at the house he had leased at 6100 West Center Avenue in Denver. On June 13 Kerouac writes that he is at “the true beginning” of On the Road.

By the first week of July, Kerouac was alone again. Gabrielle and Caroline and her family were unhappy in the west and had returned home. On July 16 Harcourt, Brace editor Robert Giroux flew to Denver to work with Kerouac on the manuscript of The Town and the City.

Kerouac typed and revised a twenty-four-page handwritten draft of the beginning of a new version of Road titled “Shades of the Prison House. Chapter 1 On the Road-May-July 1949.” The manuscript is marked New York–Colorado, indicating that Kerouac wrote the handwritten draft in Ozone Park and brought it West. “Shades of the Prison House” is informed by Kerouac’s trips with Cassady earlier in the year and the stories Cassady had told him about his boyhood, by Kerouac’s hopefulness for the impending publication of The Town and the City, and by the arrest and imprisonment of his friends in April. Kerouac may also have been remembering his arrest and brief imprisonment as a material witness and accessory after the fact in Lucien Carr’s killing of Dave Kammerer in August 1944. Above all, in this period of fragile optimism, the new version of On the Road was buoyed by Kerouac’s abiding love of God.

In a cell in the Bronx jail overlooking the Harlem River, Red Moultrie leans against the worn bars and watches the red sunset over New York the night before his release. To “the cops [Red] was just another young character of the streets—nameless, anonymous, and beat.” Brown eyes “red in the light of the sun; tall, rocky, dogged, sober-souled,” Red is twenty-seven and “growing older all the time and his life was slipping away.” He plans to go to New Orleans and has ten dollars from “Old Bull” to get there. From New Orleans, Red will drive to San Francisco with his half brother Vern Pomery Jr., and from there Red will go home to Denver to look for his wife, child, and father. Pomery is to be a representation of Cassady, and he appears here for the first time in the projected novel as an idea, a phantom presence on the far horizon of the text.

Red is haunted by “the great realities from the o

ther world which appeared to him in dreams like the dream of the shrouded stranger,” in which he is pursued through “Araby” and seeks refuge in the “Protective City.” Watching the splendid sunset Red decides to follow the direction he sees in the evening sky:

The blushing sunset on this last night in jail was a hint from immense nature telling him that all things could very well return to him if he would only pray…“God make everything right,” he prayed in a whisper. He shuddered. “I’m all alone. I want to be loved, I’ve got no place to go.” Whatever that dark thing was he kept on missing…mattered no more. He had to go home.

In August, Kerouac closed up the house and left Denver to visit Neal and Carolyn Cassady in San Francisco. In On the Road Kerouac writes:

I was burning to know what was on his mind and what would happen now, for there was nothing behind me any more, all my bridges were gone and I didn’t give a damn about anything at all.

Kerouac arrived in California as the marriage of Neal and Carolyn seemed to be imploding. Pregnant, Carolyn threw Neal out, and Jack suggested Neal come back with him to New York. They traveled east where they visited Kerouac’s first wife Edie in Grosse Pointe, Michigan. Kerouac writes that this “memorable voyage described elsewhere sometime. (In “Rain & Rivers” book).” The “Rain and Rivers” journal, a notebook given to him by Cassady in January 1949, was where Kerouac recorded the majority of the journeys and specific adventures that would come to make up the narrative of the novel. As Kerouac struggles to identify and articulate the themes of his novel in his notebooks and proto-fiction, the narrative is, perhaps unknowingly at first, recorded in these travel journals.

By late August, Jack and Neal had arrived in New York. The two friends walked all over Long Island because, as Kerouac will write in On the Road, they were so used to moving but “there was no more land, just the Atlantic Ocean and we could only go so far. We clasped hands and agreed to be friends forever.” On August 25 Kerouac resumed what he calls his “ragged work” on the road novel while with Robert Giroux he continued preparing The Town and the City for publication the following spring. Kerouac typed a fifty-four-page revised double-spaced version of “Shades of the Prison House.” The sunset now appears “goldenly” in an “opening in the firmament between great dark cloudbanks.”

The central joyous source of the universe was always there, and clear as ever, when at last some strange earthly confluence forced the clouds apart, and as if curtains were drawn by arrangement, revealed the everlasting light itself: the pearl of heaven flaming on high.

Red’s long night ends in a list of names and images from Kerouac’s travels and private mythology. Kerouac’s incantation covers pages 49–53, and these pages are single spaced in contrast to the double spacing of the rest of the typescript, suggesting the book to come, the book still to write and imagined in reverberating fragments:

Fresno, Selma, Southern Pacific Railroad; cottonfields, grapes, grapey dusk; trucks, dust, tent, San Joaquin, Mexicans, Okies, highway, red workflags; Bakersfield, boxcars, palms, moon, watermelon, gin, woman…

The typescript ends on the morning of Red’s release. Red hears birds singing “and the Sunday bells at seven did begin to peal.” On the verso of page 54 Kerouac has handwritten “Foolscap for New Beginning ‘On the Road’ Aug 25 1949-Reserving back of these pages for opening of new Part Two-THE STORY JUST BEGINS.” By hand Kerouac begins the new story set where he had just spent the summer, in Colorado. It is 1928. Old Wade Moultrie owns a two-hundred-acre farm worked by his son Smiley Moultrie and Smiley’s best friend Vern Pomery. There was “a touch of the old West” in Old Wade, and when he pulls a revolver on some “young hoodlums” trying to steal his Ford he is shot and killed. This has nothing to do, Kerouac writes, “with our heroes Red Moultrie and Vern Pomery Jr.” In a journal entry for August 29 Kerouac notes:

Resuming true serious work I find that I have grown lazy in my heart…And why that is—for one thing, indirectly speaking, I cannot for instance as yet understand why my father is dead…no meaning, all unseemly, and incomplete.

By September 6 this same journal had become the “Official Log of the ‘Hip Generation,’” as he was now calling On the Road. “I haven’t really worked since May 1948,” he writes. “Time to get going…Let’s see if I can write a novel.” The eighteen-page “Hip Generation” story Kerouac then begins to write continues the story he had begun on the back page of the August 25 version of “Shades of the Prison House,” while cutting the jail material.

Red’s mother Mary Moultrie has an affair with Dean Pomery and dies giving birth to Red’s half brother Dean Pomery Jr. Wade Moultrie’s farm has gone to ruin in the years after his death, a death Kerouac intended to stand for the passing of the values of the Old West and for the passing of a kind of moral compass, a north star certainty lost to Kerouac’s fatherless travelers.

Still Kerouac is writing around the road. The road exists in future time, to be traveled when Red gets out of jail or when he and Vern grow up out of the backstory Kerouac constructs in place of the jail episodes. Kerouac is writing the why of the road, not the road itself. He is committed to the aspirational elements of the story even as the events that inspired those elements, bringing his family West, his status as a young novelist with a future, had either collapsed or been made to seem suddenly fragile again. If he could not successfully make a home in the West perhaps the novel might also fail. It was difficult to write about Red’s leaving the prison of life to go back home to his inheritance and to his family when Kerouac was effectively homeless, his dreamed Western home collapsed; his marriage to Edie emphatically over; and the thousand-dollar “inheritance” from Harcourt vanished into the air.

For much of the rest of September Kerouac worked on The Town and the City manuscript at the New York Offices of Harcourt, Brace. When this work was finished Kerouac wrote that he was “once more ready to resume On the Road,” before confessing on September 29 that

I’ve got to admit I’m stuck with On the Road. For the first time in years I DON’T KNOW WHAT TO DO. I SIMPLY DO NOT HAVE A SINGLE REAL IDEA WHAT TO DO

The next day, and writing that he was not a “hipster…Nor am I Red Moultrie…I am not even Smitty, I’m none of them,” Kerouac claimed to have settled the problem of his inability to write:

The world really does not matter, but God has made it so, and so it matters in God, and He Hath Aims for it, which we cannot know without the understanding of obedience. There is nothing to do but give praise. This is my ethic of “art” and why so.

On October 17, 1949, Kerouac writes that it is still “impossible to say ‘Road’ has really begun.” “I really began On the Road in October of 1948,” he writes, “an entire year ago. Not much to show for a year, but the first year is always slow.” Still, Kerouac thought, the novel was “about to move.” By the end of the month Kerouac writes to “hell with it; don’t worry, simply do.” He trusted that in the “work itself” he would find his way, but writes, “still don’t feel On the Road is begun.”

In November, and writing in the back of his “On the Road Readings and Notes, 1949” journal begun in the spring of that year, where he had made notes for episodes in the novel including “The Tent in the San Joaquin Valley” and “Marin City and the barracks cops-job,” Kerouac writes a “New Itinerary and Plan.” Above a drawn map of America marked with the names of the towns and cities where the action of the novel would take place Kerouac wrote “On the Road” and “Reverting to a Simpler style – Further draft + beginning-Nov 1949.” The novel would begin in the New York jail and move through New Orleans, San Francisco, Montana, Denver, and back to Times Square in New York. The list of characters Kerouac notes includes Moultrie and “Dean Pomeray,” “Slim Jackson,” brother of Pic, “Old Bull,” and “Marylou.”

In notes and manuscript fragments written in the new year Kerouac returned to the themes of loss, uncertainty, and crowding mortality. A ten-page manuscript dated January 19, 1950, handwritten in

French and translated by Kerouac (“On the Road ECRIT EN FRANCAIS”) begins

After the death of his father—Peter Martin found himself alone in the world, and after all what is a man going to do when his father is buried deep in the ground other than die himself in his heart and know that it won’t be the last time before he dies finally in his poor mortal body, and, himself a father of children and sire of a family he will return to the original form of a piece of adventurous dust in this fatal ball of earth.

The running theme of the search for the father who is dead and the Father who is God gives us to understand that death, as Tom Clark has written, was “the ground bass of [Kerouac’s] understanding of life, the undertow that moved the deep currents in his work and gave it what Kerouac himself called… ‘that inescapable sorrowful depth that shines through.’” The deaths of his brother Gerard, his father Leo, his best friend Sebastian. His drowned dead friends among the crew of the SS Dorchester sunk by torpedo on February 3, 1943. War dead, Hiroshima dead. The bomb that had come, as Kerouac writes, was one which could “crack all our bridges and banks and reduce them to jumbles like the avalanche heap.” And it is death, in the form of the dreamed figure of the shrouded stranger, who pursues the traveler across the land.

Long before his readings in Buddhism Kerouac was intuitively attempting to reconcile a worldview that saw his lived experience both as one made painfully meaningless by his hard-wired knowledge of mortality and as one to be celebrated in every detail and at every moment precisely because, as he writes in Visions of Cody, we are soon “all going to die.” Kerouac escapes this encircling loss in the act of writing. To say what happened. To get it down before it is lost. To make mythology from your life and from the lives of your friends. This urgency pushes Kerouac to strip his writing of “made-up” stories. Life’s impermanence and the inevitability of suffering inform and motivate Kerouac’s heightened sensitivity and responsiveness to the phenomenal world. What Allen Ginsberg called his “open heart” and Kerouac himself described as being “submissive to everything, open, listening” results in a body of fiction in which the representation of the magical nature of entrancing and life-affirming fleeting detail is the outstanding feature.

Tristessa

Tristessa On the Road

On the Road The Dharma Bums

The Dharma Bums Maggie Cassidy

Maggie Cassidy Big Sur

Big Sur Dr. Sax

Dr. Sax Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46

Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46 The Sea Is My Brother

The Sea Is My Brother The Town and the City: A Novel

The Town and the City: A Novel Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Desolation Angels: A Novel

Desolation Angels: A Novel Book of Sketches

Book of Sketches Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha

Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha The Electrocution of Block 38383939383

The Electrocution of Block 38383939383 Haunted Life

Haunted Life Visions of Gerard

Visions of Gerard Orpheus Emerged

Orpheus Emerged Book of Blues

Book of Blues The Subterraneans

The Subterraneans The Haunted Life

The Haunted Life The Unknown Kerouac

The Unknown Kerouac The Town and the City

The Town and the City Visions of Cody

Visions of Cody Atop an Underwood

Atop an Underwood Lonesome Traveler

Lonesome Traveler Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg Vanity of Duluoz

Vanity of Duluoz Desolation Angels

Desolation Angels On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition)

On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition) The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel

The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel Wake Up

Wake Up The Poetry of Jack Kerouac

The Poetry of Jack Kerouac Doctor Sax

Doctor Sax