- Home

- Jack Kerouac

The Subterraneans Page 2

The Subterraneans Read online

Page 2

That morning when the party was at its pitch I was in Larry’s bedroom again admiring the red light and remembering the night we’d had Micky in there the three of us, Adam and Larry and myself, and had benny and a big sexball amazing to describe in itself—when Larry ran in and said, “Man you gonna make it with her tonight?”— “I’d shore like to—I dunno—.” —“Well man find out, ain’t much time left, whatsamatter with you, we bring all these people to the house and give em all that tea and now all my beer from the icebox, man we gotta get something out of it, work on it—.” “Oh, you like her?” — “I like anybody as far as that goes man—but I mean, after all.”—Which led me to a short unwillful abortive fresh effort, some look, glance, remark, sitting next to her in corner, I gave up and at dawn she cut out with the others who all went for coffee and I went down there with Adam to see her again (following the group down the stairs five minutes later) and they were there but she wasn’t, independently darkly brooding, she’d gone off to her stuffy little place in Heavenly Lane on Telegraph Hill.

So I went home and for several days in sexual phantasies it was she, her dark feet, thongs of sandals, dark eyes, little soft brown face, Rita-Savage-like cheeks and lips, little secretive intimacy and somehow now softly snakelike charm as befits a little thin brown woman disposed to wearing dark clothes, poor beat subterranean clothes. …

A few nights later Adam with an evil smile announced he had run into her in a Third Street bus and they’d gone to his place to talk and drink and had a big long talk which Leroy-like culminated in Adam sitting naked reading Chinese poetry and passing the stick and ending up laying in the bed, “And she’s very affectionate, God, the way suddenly she wraps her arms around you as if for no other reason but pure sudden affection.” — “Are you going to make it? have an affair with her?” — “Well now let me—actually I tell you—she’s a whole lot and not a little crazy—she’s having therapy, has apparently very seriously flipped only very recently, something to do with Julien, has been having therapy but not showing up, sits or lies down reading or doing nothing but staring at the ceiling all day long in her place, eighteen dollars a month in Heavenly Lane, gets, apparently, some kind of allowance tied up somehow by her doctors or somebody with her inadequacy to work or something—is always talking about it and really too much for my likings—has apparently real hallucinations concerning nuns in the orphanage where she was raised and has seen them and felt actual threat—and also other things, like the sensation of taking junk although she’s never had junk but only known junkies.” — “Julien?” — “Julien takes junk whenever he can which is not often because he has no money and his ambition like is to be a real junkey—but in any case she had hallucinations of not being properly contact high but actually somehow secretly injected by someone or something, people who follow her down the street, say, and is really crazy—and it’s too much for me—and finally being a Negro I don’t want to get all involved.” — “Is she pretty?”—“Beautiful—but I can’t make it.”—“But boy I sure dig her looks and everything else.”—“Well allright man then you’ll make it—go over there, I’ll give you the address, or better yet when, I’ll invite her here and we’ll talk, you can try if you want but although I have a hot feeling sexually and all that for her I really don’t want to get any further into her not only for these reasons but finally, the big one, if I’m going to get involved with a girl now I want to be permanent like permanent and serious and long termed and I can’t do that with her.”—“I’d like a long permanent, et cetera.”—“Well we’ll see.”

He told me of a night she’d be coming for a little snack dinner he’d cook for her so I was there, smoking tea in the red living-room, with a dim red bulb light on, and she came in looking the same but now I was wearing a plain blue silk sports shirt and fancy slacks and I sat back cool to pretend to be cool hoping she would notice this with the result, when the lady entered the parlor I did not rise.

While they ate in the kitchen I pretended to read. I pretended to pay no attention whatever. We went out for a walk the three of us and by new all of us vying to talk like three good friends who want to get in and say everything on their minds, a friendly rivalry—we went to the Red Drum to hear the jazz which that night was Charlie Parker with Honduras Jones on drums and others interesting, probably Roger Beloit too, whom I wanted to see now, and that excitement of softnight San Francisco bop in the air but all in the cool sweet unexerting Beach—so we in fact ran, from Adam’s on Telegraph Hill, down the white street under lamps, ran, jumped, showed off, had fun—felt gleeful and something was throbbing and I Was pleased that she was able to walk as fast as we were—a nice thin strong little beauty to cut along the street with and so striking everyone turned to see, the strange bearded Adam, dark Mardou in strange slacks, and me, big gleeful hood.

So there we were at the Red Drum, a tableful of beers a few that is and all the gangs cutting in and out, paying a dollar quarter at the door, the little hip-pretending weazel there taking tickets, Paddy Cordavan floating in as prophesied (a big tall blond brakeman type subterranean from Eastern Washington cowboy-looking in jeans coming in to a wild generation party all smoky and mad and I yelled “Paddy Cordavan?” and “Yeah?” and he’d come over)—all sitting together, interesting groups at various tables, Julien, Roxanne (a woman of 25 prophesying the future style of America with short almost crewcut but with curls black snaky hair, snaky walk, pale pale junkey anemic face and we say junkey when once Dostoevsky would have said what? if not ascetic or saintly? but not in the least? but the cold pale booster face of the cold blue girl and wearing a man’s white shirt but with the cuffs undone untied at the buttons so I remember her leaning over talking to someone after having slinked across the floor with flowing propelled shoulders, bending to talk with her hand holding a short butt and the neat little flick she was giving it to knock ashes but repeatedly with long long fingernails an inch long and also orient and snakelike)—groups of all kinds, and Ross Wallenstein, the crowd, and up on the stand Bird Parker with solemn eyes who’d been busted fairly recently and had now returned to a kind of bop dead Frisco but had just discovered or been told about the Red Drum, the great new generation gang wailing and gathering there, so here he was on the stand, examining them with his eyes as he blew his now-settled-down-into-regulated-design “crazy” notes—the booming drums, the high ceiling—Adam for my sake dutifully cutting out at about 11 o’clock so he could go to bed and get to work in the morning, after a brief cutout with Paddy and myself for a quick ten-cent beer at roaring Pantera’s, where Paddy and I in our first talk and laughter together pulled wrists—now Mardou cut out with me, glee eyed, between sets, for quick beers, but at her insistence at the Mask instead where they were fifteen cents, but she had a few pennies herself and we went there and began earnestly talking and getting hightingled on the beer and now it was the beginning—returning to the Red Drum for sets, to hear Bird, whom I saw distinctly digging Mardou several times also myself directly into my eye looking to search if really I was that great writer I thought myself to be as if he knew my thoughts and ambitions or remembered me from other night clubs and other coasts, other Chicagos—not a challenging look but the king and founder of the bop generation at least the sound of it in digging his audience digging the eyes, the secret eyes him-watching, as he just pursed his lips and let great lungs and immortal fingers work, his eyes separate and interested and humane, the kindest jazz musician there could be while being and therefore naturally the greatest—watching Mardou and me in the infancy of our love and probably wondering why, or knowing it wouldn’t last, or seeing who it was would be hurt, as now, obviously, but not quite yet, it was Mardou whose eyes were shining in my direction, though I could not have known and now do not definitely know—except the one fact, on the way home, the session over the beer in the Mask drunk we went home on the Third Street bus sadly through night and throb knock neons and when I suddenly leaned over her to shout something further (in her secret self

as later confessed) her heart leapt to smell the “sweetness of my breath” (quote) and suddenly she almost loved me—I not knowing this, as we found the Russian dark sad door of Heavenly Lane a great iron gate rasping on the sidewalk to the pull, the insides of smelling garbage cans sad-leaning together, fish heads, cats, and then the Lane itself, my first view of it (the long history and hugeness of it in my soul, as in 1951 cutting along with my sketchbook on a wild October evening when I was discovering my own writing soul at last I saw the subterranean Victor who’d come to Big Sur once on a motorcycle, was reputed to have gone to Alaska on same, with little subterranean chick Dorie Kiehl, there he was in striding Jesus coat heading north to Heavenly Lane to his pad and I followed him awhile, wondering about Heavenly Lane and all the long talks I’d been having for years with people like Mac Jones about the mystery, the silence of the subterraneans, “urban Thoreaus” Mac called them, as from Alfred Kazin in New York New School lectures back East commenting on all the students being interested in Whitman from a sexual revolution standpoint and in Thoreau from a contemplative mystic and antimaterialistic as if existentialist or whatever standpoint, the Pierre-of-Melville goof and wonder of it, the dark little beat burlap dresses, the stories you’d heard about great tenormen shooting junk by broken windows and starting at their horns, or great young poets with bears lying high in Rouault-like saintly obscurities, Heavenly Lane the famous Heavenly Lane where they’d all at one time or another the bat subterraneans lived, like Alfred and his little sickly wife something straight out of Dostoevsky’s Petersburg slums you’d think but really the American lost bearded idealistic—the whole thing in any case), seeing it for the first time, but with Mardou, the wash hung over the court, actually the back courtyard of a big 20-family tenement with bay windows, the wash hung out and in the afternoon the great symphony of Italian mothers, children, fathers BeFinneganing and yelling from stepladders, smells, cats mewing, Mexicans, the music from all the radios whether bolero of Mexican or Italian tenor of spaghetti eaters or loud suddenly turned-up KPFA symphonies of Vivaldi harpsichord intellectuals performances boom blam the tremendous sound of it which I then came to hear all the summer wrapt in the arms of my love—walking in there now, and going up the narrow musty stairs like in a hovel, and her door.

Plotting I demanded we dance—previously she’d been hungry so I’d suggested and we’d actually gone and bought egg foo young at Jackson and Kearny and now she heated this (later confession she’d hated it though it’s one of my favorite dishes and typical of my later behavior I was already forcing down her throat that which she in subterranean sorrow wanted to endure alone if at all ever), ah.—Dancing, I had put the light out, so, in the dark, dancing, I kissed her—it was giddy, whirling to the dance, the beginning, the usual beginning of lovers kissing standing up in a dark room the room being the woman’s the man all designs—ending up later in wild dances she on my lap or thigh as I danced her around bent back for balance and she around my neck her arms that came to warm. so much the me that then was only hot—

And soon enough I’d learn she had no belief and had had no place to get it from—Negro mother dead for birth of her—unknown Cherokee-halfbreed father a hobo who’d come throwing torn shoes across gray plains of fall in black sombrero and pink scarf squatting by hotdog fires casting Tokay empties into the night “Yaa Calexico!”

Quick to plunge, bite, put the light out, hide my face in shame, make love to her tremendously because of lack of love for a year almost and the need pushing me down—our little agreements in the dark, the really should-not-be-tolds—for it was she who later said “Men are so crazy, they want the essence, the woman is the essence, there it is right in their hands but they rush off erecting big abstract constructions.”—“You mean they should just stay home with the essence, that is lie under a tree all day with the woman but Mardou that’s an old idea of mine, a lovely idea, I never heard it better expressed and never dreamed.”—“Instead they rush off and have big wars and consider women as prizes instead of human beings, well man I may be in the middle of all this shit but I certainly don’t want any part of it” (in her sweet cultured hip tones of new generation).—And so having had the essence of her love now I erect big word constructions and thereby betray it really—telling tales of every gossip sheet the washline of the world—and hers, ours, in all the two months of our love (I thought) only once-washed as she being a lonely subterranean spent mooningdays and would go to the laundry with them but suddenly it’s dank late afternoon and too late and the sheets are gray, lovely to me—because soft.—But I cannot in this confession betray the innermosts, the thighs, what the thighs contain—and yet why write?—the thighs contain the essence—yet tho there I should stay and from there I came and’ll eventually return, still I have to rush off and construct construct—for nothing—for Baudelaire poems—

Never did she use the word love, even that first moment after our wild dance when I carried her still on my lap and hanging clear to the bed and slowly dumped her, suffered to find her, which she loved, and being unsexual in her entire life (except for the first 15-year-old conjugality which for some reason consummated her and never since) (0 the pain of telling these secrets which are so necessary to tell, or why write or live) now “casus in eventu est” but glad to have me losing my mind in the slight way egomaniacally I might on a few beers.—Lying then in the dark, soft, tentacled, waiting, till sleep—so in the morning I wake from the scream of beermares and see beside me the Negro woman with parted lips sleeping, and little bits of white pillow stuffing in her black hair, feel almost revulsion, realize what a beast I am for feeling anything near it, grape little sweet-body naked on the restless sheets of the nightbefore excitement, the noise in Heavenly Lane sneaking in through the gray window, a gray doomsday in August so I feel like leaving at once to get “back to my work” the chimera of not the chimera but the orderly advancing sense of work and duty which I had worked up and developed at home (in South City) humble as it is, the comforts there too, the solitude which I wanted and now can’t stand.—I got up and began to dress, apologize, she lay like a little mummy in the sheet and cast the serious brown eyes on me, like eyes of Indian watchfulness in a wood, like with the brown lashes suddenly rising with black lashes to reveal sudden fantastic whites of eye with the brown glittering iris center, the seriousness of her face accentuated by the slightly Mongoloid as if of a boxer nose and the cheeks puffed a little from sleep, like the face on a beautiful porphyry mask found long ago and Aztecan.—“But why do you have to rush off so fast, as though almost hysterical or worried?”—“Well I do I have work to do and I have to straighten out—hangover—” and she barely awake, so I sneak out with a few words in fact when she lapses almost into sleep and I don’t see her again for a few days—

The adolescent cocksman having made his conquest barely broods at home the loss of the love of the conquered lass, the blacklash lovely—no confession there.—It was on a morning when I slept at Adam’s that I saw her again, I was going to rise, do some typing and coffee drinking in the kitchen all day since at that time work, work was my dominant thought, not love—not the pain which impels me to write this even while I don’t want to, the pain which won’t be eased by the writing of this but heightened, but which will be redeemed, and if only it were a dignified pain and could be placed somewhere other than in this black gutter of shame and loss and noisemaking folly in the night and poor sweat on my brow—Adam rising to go to work, I too, washing, mumbling talk, when the phone rang and it was Mardou, who was going to her therapist, but needed a dime for the bus, living around the corner, “Okay come on over but quick I’m going to work or I’ll leave the dime with Leo.”—“O is he there?”—“Yes.”—In my mind man-thoughts of doing it again and actually looking forward to seeing her suddenly, as if I’d felt she was displeased with our first night (no reason to feel that, previous to the balling she’d lain on my chest eating the egg foo young and dug me with glittering glee eyes) (that tonight my ene

my devour?) the thought of which makes me drop my greasy hot brow into a tired hand—0 love, fled me—or do telepathies cross sympathetically in the night?—Such ca-coëthes him befalls—that the cold lover of lust will earn the warm bleed of spirit—so she came in, 8 A.M., Adam went to work and we were alone and immediately she curled up in my lap, at my invite, in the big stuffed chair and we began to talk, she began to tell her story and I turned on (in the gray day) the dim red bulblight and thus began our true love—

Tristessa

Tristessa On the Road

On the Road The Dharma Bums

The Dharma Bums Maggie Cassidy

Maggie Cassidy Big Sur

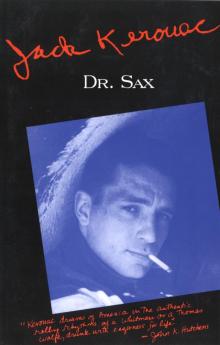

Big Sur Dr. Sax

Dr. Sax Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46

Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46 The Sea Is My Brother

The Sea Is My Brother The Town and the City: A Novel

The Town and the City: A Novel Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Desolation Angels: A Novel

Desolation Angels: A Novel Book of Sketches

Book of Sketches Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha

Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha The Electrocution of Block 38383939383

The Electrocution of Block 38383939383 Haunted Life

Haunted Life Visions of Gerard

Visions of Gerard Orpheus Emerged

Orpheus Emerged Book of Blues

Book of Blues The Subterraneans

The Subterraneans The Haunted Life

The Haunted Life The Unknown Kerouac

The Unknown Kerouac The Town and the City

The Town and the City Visions of Cody

Visions of Cody Atop an Underwood

Atop an Underwood Lonesome Traveler

Lonesome Traveler Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg Vanity of Duluoz

Vanity of Duluoz Desolation Angels

Desolation Angels On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition)

On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition) The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel

The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel Wake Up

Wake Up The Poetry of Jack Kerouac

The Poetry of Jack Kerouac Doctor Sax

Doctor Sax