- Home

- Jack Kerouac

The Town and the City: A Novel Page 2

The Town and the City: A Novel Read online

Page 2

The few boy friends that she goes out with are all big husky creatures like herself who work on farms or drive trucks or handle the heavy work in factories. When one of them cuts his finger or burns his hand, she sits him down and administers the necessary aid, and scolds him furiously. She is the first member of the family to get up in the morning, and the last in bed. As far back as she can remember she has been a “big sister.” There she is at dusk, standing in the yard taking down the wash, packing it in baskets and starting back to the porch, pausing for only a moment to scowl at the children playing in the field nearby, and then shaking her head and disappearing inside the house.

The eldest son is Joe, at this time around seventeen years old. This is the kind of thing he does: he borrows a buddy’s old car—a ’31 Auburn—and in company with a wild young wrangler like himself drives up to Vermont to see his girl. That night, after the stamping furors of roadside polkas with their girl friends, Joe runs the car off a curve and into a tree and they are all scattered around the wreck with minor injuries. Joe lies flat on his back in the middle of the highway, thinking: “Wow! Maybe it’ll be better if I make out I’m almost dead—otherwise I’ll get in trouble with the cops and catch holy hell from the old man.”

They take Joe and the others to the hospital, where he lies in a “coma” for two days, saying nothing, peeking furtively around, listening. The doctors believe he has suffered serious internal injuries. Once in a while the local police come around to make inquiries. Joe’s buddy from Galloway, who has only suffered a minor laceration, is soon up out of bed, flirting with the nurses, helping with the dishes in the hospital kitchen, wondering what next to do. He comes to Joe’s bedside twenty times a day.

“Hey, Joe, when are you gonna get better, pal?” he moans. “What’s the matter with you? Oh, why did this have to happen!”

Finally Joe whispers, “Shut up, for krissakes,” and closes his eyes again gravely, almost piously, with mad propriety and purpose, as the other boy gapes in amazement.

That night Joe’s father comes driving over the mountains in the night to fetch his wild and crazy son. In the middle of the night Joe leaps out of bed and dresses and runs out of the hospital gleefully, and a moment later he is driving them all back to Galloway at seventy miles per hour.

“This is the last time you’re going on any of these damn trips of yours!” vows Mr. Martin, puffing furiously on his cigar. “Do you hear me?”

His mother fears that he will come home on crutches, maimed for life, but in the morning she looks out the window and there’s her son Joe stretched out in the backyard underneath the old ’29 Ford, launched on an overhauling job, with a smudge of oil on his lip like a little mustache so that he looks “just like Errol Flynn” somehow. And the next day, Joe is to be seen high-diving from the window of a tenement overlooking a Galloway canal, in the mill district, where he has himself a sweetheart. Joe always has a job, always earns money, and never seems to find time to mope and sulk. His next goal is a motorcycle wild with rabbit-tails and blazing buttons.

His brother, Francis Martin, is always moping and sulking. Francis is tall and skinny, and the first day he goes to High School he walks along the corridors staring at everyone in a sullen and sour manner, as though to ask: “Who are all these fools?” Only fifteen years old at the time, Francis has a habit of keeping to himself, reading or just staring out the window of his bedroom. His family “can’t figure him out.” Francis is the twin brother of the late and beloved little Julian, and like Julian his health is not up to par with the rest of the Martins. But his mother loves him and understands him.

“You can’t expect too much from Francis,” she always says, “he’s not well and probably never will be. He’s a strange boy, you’ve just got to understand him.”

Francis surprises them all by exhibiting a facile brilliance in his schoolwork, amassing one of the highest records in the history of the school—but his mother understands that too. He is a dour, gloomy, thinlipped youngster, with a slight stoop in his posture, cold blue eyes, and an air of inviolable dignity and tact. In a large family like the Martins, when one member keeps aloof from the others, he is always regarded with suspicion but at the same time curiously respected. Francis Martin, a recipient of this respect, is thus made early aware of the power of secretiveness.

“You can’t rush Francis,” says the mother. “He’s his own boss and he’ll do what he likes when the time comes. If he keeps so much to himself it’s because he has a lot on his mind.”

“If you ask me,” says Rosey, “he’s just got something wrong up here.” And she twirls her big finger around her ear. “You mark my word.”

“No,” says Mrs. Martin, “you just don’t understand him.”

Ruth Martin at this time is eighteen years old, a senior in High School. She goes to the dances, the skating parties, the football games of high school life, a diminutive, quiet, well-mannered little girl with a cheerful and generous temperament. She is a well beloved member of the family of whom it is expected that she will marry in time, raise her children and meet responsibilities in her patient, reliable and merry way, as she has always done. Now she wants to attend a business college in order to learn secretarial work and be self-sufficient for a few years. Ruth is that kind of a girl who makes no smash in the world, the girl you never hear of, but see everywhere, a woman before all things who keeps her soul to herself and for one heart.

Thirteen-year-old Peter Martin is shocked when he sees his sister Ruth dancing so closely to another boy at the high school dance—after the annual minstrel show in the school auditorium. Looking over the entire dance floor, rose-hued and misty and lovely, he decides that life is more exciting than he supposed it was allowed. It is 1935, the orchestra is playing Larry Clinton’s “Study in Red” and everyone begins to sense the thrilling new music that is about to develop without limit. There are rumors of Benny Goodman in the air, of Fletcher Henderson and of new great orchestras rising. In the crowded ballroom, the lights, the music, the dancing figures, the echoes all fill the boy with strange new feelings and mysterious sorrow.

By the window Peter gazes out on the brooding Spring darkness, burning with the vision of the close-embracing dancers, stirred by the tidings of the music and filled with an infinite longing to grow up and go to high school himself, where he too can dance embraced with shapely girls, sing in the minstrel show, and perhaps be a football hero too.

“See that fellow with the crew-cut?” Ruth points out for him. “The chunky one over there, dancing with that pretty blonde? That’s Bobby Stedman.”

To Peter, Bobby Stedman is a name emblazoned on hallowed sports pages, a weaving misty figure in the newsreel shots of the Galloway-Lawton game on Thanksgiving Day, a hero of heroes. Something dark and proud and remote surrounds his name, his figure, his atmosphere. As he dances there, Peter cannot believe his eyes—can this be Bobby Stedman himself? Isn’t he the greatest, speediest, hardest-running, weavingest halfback in the state? Haven’t they printed his name in big black letters, isn’t there a slow pompous music to his name and to the proud dark world surrounding him?

Then Peter realizes that Ruth is dancing with Lou White, himself. Lou White, another remote and heroic name, a figure on rainswept or snowlashed fields, a face in the newspapers glowering in exertion over the taut center position.…

When Lou White comes to the Martin house to take Ruth skating, Peter stands in a dark corner and looks long at him in sheepish awe. When Lou White stays awhile to listen to the Jack Benny program, and laughs at the jokes, Peter is completely amazed. And when again he sees him on the day of the big Thanksgiving game, far down on the field hunched over the ball, Peter can’t believe that this remote god has come to his house to see his sister and laugh at jokes. The crowds roar, the Autumn wind whips among the flags around the stadium, Lou White far away snaps back the ball on the striped field, makes sensational tackles that evoke roars, trots about and is cheered thunderously off the field as he l

eaves his last game for the school. The bands play the alma mater song, broken in the wind.

“I’m going to be playing in this game in two years,” says Peter to his father.

“Oh, you will, hey?”

“Yes.”

“Don’t you think you’re a little too small for that? Those boys out there are built like trucks.”

“I’ll get bigger,” says Peter, “and strong too.”

His father laughs, and from that moment Peter Martin is finally goaded on by all the fantastic and fabulous triumphs that he sees possible in the world.

If on some soft odorous April night the twelve-year-old Elizabeth Martin is seen strolling mournfully beneath the dripping wet trees, pouting and fierce and lonely, with her hands plunged deep in the pockets of her little tan raincoat as she considers the horrid legend of life, and broods as she returns slowly to her family’s house—be sure that the darkness and terror of twelve-years-old will come to womanly days of ripe warm sunshine.

Or if that boy there, the one with the resolute little face, who wets his lips briefly before replying to a question, who strides along with determination and absorption towards his objective, who tinkers solemnly in the cellar or garage with a gadget or old motor, says very little and looks at everyone with a level blue-eyed stare of absolute reasonableness, if that boy, nine-year-old Charley Martin, is examined carefully as he goes about the undertakings of his self-assured and earnest young existence, dark wings appear above him as if to shade a strange light in his thoughtful eyes.

And finally, if on some snowy dusk, with the sun’s sloping light on the flank of a hill, with the sun flaming back from factory windows, you see a little child of six, a boy called Mickey Martin, standing motionless in the middle of the road with his sled behind him, stunned by the sudden discovery that he does not know who he is, where he came from, what he is doing here, remember that all children are first shocked out of the womb of a mother’s world before they can know that loneliness is their heritage and their only means of rediscovering men and women.

This is the Martin family, the elders and the young ones, even the little ones, the flitting ghost-ends of a brood who will grow and come to attain size and seasons and huge presence like the others, and burn savagely across days and nights of living, and give brooding rare articulation to the poor things of life, and the rich, dark things too.

[3]

Over Galloway and over this house the weathers proceed, flanking across the skies in seasonal majesty. The great Winter rumbles at its very foundations and melts, there is water trickling underneath the snow, the ice-floes throng at the Falls, and the air is suddenly noisy with a lyrical thaw.

Young Peter Martin hears the long echoing hoot of the Montreal train broken and interrupted by some vast shifting in the March air, he hears voices coming suddenly on the breeze from across the river, barkings, calls, hammerings, which cease almost as soon as they come. He sits at the window awake with expectation, the eaves drip, something echoes like far thunder. He looks up at broken clouds fleeing across the ragged heavens, whipping over his roof, over the swaying trees, disappearing in hordes, advancing in armies. There’s a smell of gummy birch, rank and teeming smells like mud that’s dark and moist, of dark unlimbering branches of last Autumn’s matted floor dissolving in a fragrant mash, of whole advancing waves of air, misty March air.

There’s something dizzy and wild in his heart, he hurries out on the street and paces the sidewalks, all around him there’s a grand melting, blown adrift, something soft and musical, a thaw, a hint of warmth, a breath. On the street the sagging snowbank, the running gutter, the noisy thaw, the lyrical newness everywhere. He hurries along filled with unspeakable premonitions of Spring, he must hurry over to Danny’s house and play with him in the melting snow, make snowballs, throw them across the misty air against black oozing tree-trunks, shout amid all the sudden sounds that carry in the air from everywhere.

“When the snow melts we’ll play pepper just to unloose the ole throwin’ arm, get that homerun swing back, huh, Dan?”

“Yow!”

The boy’s “Yow!” echoes across the field like the sound of a horn. They build a snowman and riddle it with snowballs, and now dusk is coming and March sky is mad and lowering with angry, purple clouds. In a moment the sun is going to break through and flame in all the windows of Galloway, the mill windows will be a thousand red flambeaux, something will slant across the skies and over the river.

“Yow!”

Then the rains come, April washes the snow with water and carries it down to the mad roaring river, tree-trunks come floating down from New Hampshire, the falls are in a turmoil, gray, dirty yellow waters boil and explode on the rocks heaving up sticks and logs. The kids race along the riverbank throwing things in the water. They build fires and yell jubilantly.

One day, suddenly, dusk settles in a hush of quiet, the sun goes down huge and red, and an odorous silent darkness takes over, as treeleaves swish softly in a breeze all smelling of foliage and loam. There’s a big brown moon rising on the horizon. The old people of Galloway go out and stand on the porch awhile, remembering the old songs. Big George Martin lights a cigar and looks at the moon. The fragrance of the cigar smoke lingers on the porch, there’s no wind, no more noise and fury. “Will you love me in December as you do in May …”

In the morning, as the sun comes up warm, as a vast chorale of birds is taken up in the branches everywhere, as the suggestion of sweet blossoms spreads in the air, it is May.

Little Mickey wakes up and goes to his window: it’s Saturday morning, no school today. And for him there’s a still music in the air like the faint sound of heraldry over the woods, like men, horses and dogs gathering under the trees far across the field for some joyous and adventurous foray. Everything is soft and musical, and sweet, and full of longings, misty hints and unspeakable revelations that float in the gentlest blue air. There, in the blue shadows beneath the morning trees, in the cool speckled shade, in the new green misty color of the woods far off, in the dark ground still moist and all covered with little blossoms, there is his hint of glorious spreading Summer, and the future. Mickey dashes out, slamming the kitchen door behind him, goes rolling his old rubber tire with a stick. He journeys down old Galloway Road over the cool dewy tar, on each side of him the birds are singing, he wonders when there’ll be apples in old man Breton’s orchard there. He figures this year he will explore the river in a boat. This year he will do everything, boy!

In the middle of the morning Mickey watches all the big guys at the ballfield slamming their fists into their gloves, throwing a brand new white baseball around. Someone has a bat, hitting light bunts, the boys stoop to pick up the grounders and yell, “Uff! I got them old kinks this year!”

Someone hoots under a high fly, punches his glove, pulls it down, trots around awhile, lobs the ball back easily. It’s Spring training time, they’ve got to watch “the old arm.” Mickey smells the fragrant cigarette smoke in the morning air where the older boys stand around talking. Big brother Joe Martin is winding up leisurely, throwing to another boy who squats with a catcher’s mitt. Joe is a star pitcher, he knows how to take his time and get the old kinks out in the Spring. Everybody watches as he lobs the ball in easily, with a sure motion and a deadpan face. A minute later he’s whooping with laughter when someone gets a knock on the shins from a hard grounder.

In his mother’s cool shady kitchen, Mickey devours a bowl of cereal and stares at the picture of Jimmy Foxx on the box cover. His chums are coming up the road, he can hear them, they’re going off to play cowboys on the hill. He’s Buck Jones all the time. They’re out in the yard now, calling:

“Mick-ee!”

Mickey comes storming out of the kitchen with both guns blazing, “Kow! kow! kow!” and dodges behind a barrel; the others take cover and return fire. Someone leaps up, twists, contorts, and falls slain to the grass.

In the Spring night, Joe tunes up the old Ford and roars off

to drink beer with his buddies. And on the first warm June night, Mrs. Martin and Ruth dust off the old swing in the backyard, put cushions on it, make a big bowl of popcorn, and go sit under the moon, in the waving black shade of the high hedges.

A cousin sits with them in the breezy night, exclaiming: “Ooh! ain’t the moon grand!”

Old man Martin, banging around the kitchen making an egg sandwich, mimics savagely: “Ain’t the moon gry-and!”

The three women out in the yard, swinging rhythmically in the creaking old swing, are telling each other about the best fortunetellers they have ever known.

“I tell you, Marge, she is uncanny!”

Mrs. Martin rocks in the swing, waiting patiently, with slitted eyes, skeptical.

“She foretold almost everything that happened that year, detail by detail, mind you!” And with this Cousin Leona looks up at the moon and sighs, “The irony of this life, Marge, the irony of life.”

The father of the house stomps out of the kitchen with his sandwich, mimicking again, savagely: “Oh, the irony of liaf!”

The women rock back and forth in the old creaking swing, reaching mechanically into the popcorn bowl, musing, contented, belonging to the wonderful darkness and the ripe June world, owning it, as no barging man of the house could ever hope to belong to any part of the earth or own an inch of it.

By the New England lake on a July night, the young people dance in a lanterned breeze-ruffled ballroom, the lights are soft blue and rose, the moon is bright on the dark waters out beyond the balcony. The songs are sweetly felt, to be sweetly remembered. The young lovers cling, whisper, dance. On a diving raft off the lake beach, young people sit with their feet dangling in the soft waters of the night, they hear the music from the ballroom floating over the lake. In a honkytonk saloon where Joe is drinking beer by the gallons and dancing the polka with big Polish and French-Canadian blondes, the smoke is thick, there’s tumult of fiddles and stamping feet, and the sight of the lake and the moon out the screen windows is darkly beautiful, a lone pine soughs in the breeze just outside the windows. A lonely youth sick from beer and dizzy with the night’s fragrance walks along the shore of the lake in a confused reverie. He hears music coming from over there, where they dance, the dark breeze brings it to him in a remote fusion of melancholy sounds. The cool potent heavy-scented magnificent night, the smell of pine, the reeds swaying in shallow water, the thronging sounds of toads and crickets, and the great round brown moon with its sideways brooding, somehow compassionate, sad big face.

Tristessa

Tristessa On the Road

On the Road The Dharma Bums

The Dharma Bums Maggie Cassidy

Maggie Cassidy Big Sur

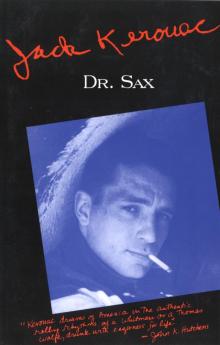

Big Sur Dr. Sax

Dr. Sax Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46

Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46 The Sea Is My Brother

The Sea Is My Brother The Town and the City: A Novel

The Town and the City: A Novel Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Desolation Angels: A Novel

Desolation Angels: A Novel Book of Sketches

Book of Sketches Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha

Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha The Electrocution of Block 38383939383

The Electrocution of Block 38383939383 Haunted Life

Haunted Life Visions of Gerard

Visions of Gerard Orpheus Emerged

Orpheus Emerged Book of Blues

Book of Blues The Subterraneans

The Subterraneans The Haunted Life

The Haunted Life The Unknown Kerouac

The Unknown Kerouac The Town and the City

The Town and the City Visions of Cody

Visions of Cody Atop an Underwood

Atop an Underwood Lonesome Traveler

Lonesome Traveler Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg Vanity of Duluoz

Vanity of Duluoz Desolation Angels

Desolation Angels On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition)

On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition) The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel

The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel Wake Up

Wake Up The Poetry of Jack Kerouac

The Poetry of Jack Kerouac Doctor Sax

Doctor Sax