- Home

- Jack Kerouac

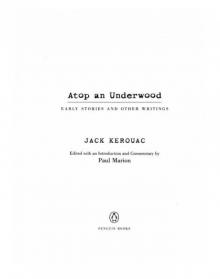

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Page 22

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Read online

Page 22

“What time is it?” yawned Wesley.

“One-thirty.”

“Shuck-all! I’ve been sleepin’ ... and dreamin’ too,” said Wesley, drawing deep from his cigarette.

Everhart approached Wesley’s side. “Well, Wes,” he began, “I’m going with you—or that is, I’m shipping out. Do you mind if I follow you along? I’m afraid I’d be lost alone, with all the union hall and papers business ...”

“Hell, no, man!” Wesley smiled. “Ship with me!”

“Let’s shake on that!” smiled the other, proffering his hand. Wesley wrung his hand with grave reassurance.

Everhart began to pack with furious energy, laughing and chatting. Wesley told him he knew of a ship in Boston bound for Greenland, and that getting one’s Seaman’s papers was a process of several hours duration. They also planned to hitchhike to Boston that very afternoon. [...]

Everhart, busy rummaging in the closet, made no remarks, so Wesley followed Sonny into the dim hall and into another room.

This particular room faced the inner court of the building, so that no sun served to brighten what ordinarily would be a gloomy chamber in the first place. A large man clad in a brown bathrobe sat by the window smoking a pipe. The room was furnished with a large bed, an easy chair (in which the father sat), another smaller chair, a dresser, a battered trunk, and an ancient radio with exterior loudspeaker and all. From this radio there now emitted a faint strain of music through a clamor of static.

“Hey Paw!” sang Sonny. “Here’s that sailor!”

The man turned from his reverie and fixed two red-rimmed eyes on them, half stunned. Then he perceived Wesley and smiled a pitifully twisted smile, waving his hand in salute.

Wesley waved back, greeting: “Hullo!”

“How’s the boy?” Mr. Everhart wanted to know, in a deep, gruff, workingman’s voice.

“Fine,” Wesley said.

“Billy’s goin’ with you, hey?” the father smiled, his mouth twisted down into a chagrined pout, as though to smile was to admit defeat. “I always knew the little cuss had itchy feet.”

Wesley sat down on the edge of the bed while Sonny ran to the foot of the bed to preside over them proudly.

“This is my youngest boy,” said the father of Sonny. “I’d be a pretty lonely man without him. Everybody else seems to have forgotten me.” He coughed briefly. “Your father alive, son?” he resumed.

Wesley leaned a hand on the mottled bedspread: “Yeah. He’s in Boston.”

“Where’s your people from?”

“Vermont originally.”

“Vermont? What part?”

“Bennington,” answered Wesley. “My father owned a service station there for twenty-two years.”

“Bennington,” mused the old man, nodding his head in reflection. “I traveled through there many years ago. Long before your time.”

“His name’s Charley Martin,” supplied Wesley.

“Martin? ... I used to know a Martin from Baltimore, a Jack Martin he was.”

There was a pause during which Sonny slapped the bedstead. Outside, the sun faded once more, plunging the room into a murky gloom. The radio sputtered with static.

Bill’s sister entered the room, not even glancing at Wesley.

“Is Bill in his room?” she demanded.

The old man nodded: “He’s packing his things, I guess.”

“Packing his things?” she cried. “Don’t tell me he’s really going through with this silly idea?”

Mr. Everhart shrugged.

“For God’s sake, Pa, are you going to let him do it?”

“It’s none of my business—he has a mind of his own,” returned the old man calmly, turning toward the window.

“He has a mind of his own!” she mimicked savagely.

“Yes he has!” roared the old man, spinning around to face his daughter angrily. “I can’t stop him.”

She tightened her lips irritably for a moment.

“You’re his father aren’t you!” she shouted.

“Oh!” boomed Mr. Everhart with a vicious leer. “So now I’m the father of the house!”

The woman stamped out of the room with an outraged scoff.

“That’s a new one!” thundered the father after her.

Sonny snickered mischievously.

“That’s a new one!” echoed the old man to himself. “They dumped me in this back room years ago when I couldn’t work any more and forgot all about it. My word in this house hasn’t meant anything for years.”

Wesley fidgeted nervously with the hem of the old quilt blanket.

“You know, son,” resumed Mr. Everhart with a sullen scowl, “a man’s useful in life so long’s he’s producin’ the goods, bringin’ home the bacon; that’s when he’s Pop, the breadwinner, and his word is the word of the house. No sooner he grows old an’ sick an’ can’t work any more, they flop him up in some old corner o’ the house,” gesturing at his room, “and forget all about him, unless it be to call him a damn nuisance.”

From Bill’s room they could hear arguing voices.

“I ain’t stoppin’ him from joining the merchant marine if that’s what he wants,” grumbled the old man. “And I know damn well I couldn’t stop him if I wanted to, so there!” He shrugged wearily.

Wesley tried to maintain as much impartiality as he could; he lit a cigarette nervously and waited patiently for a chance to get out of this uproarious household. He wished he had waited for Bill at a nice cool bar.

“I suppose it’s none too safe at sea nowadays,” reflected Mr. Everhart aloud.

“Not exactly,” admitted Wesley.

“Well, Bill will have to face danger sooner or later, Army or Navy or merchant marines. All the youngsters are in for it,” he added dolefully. “Last war, I tried to get in but they refused me—wife n’ kids. But this is a different war, all the boys are going in this one.”

The father laid aside his pipe on the window sill, leaning over with wheezing labor. Wesley noticed he was quite fat; the hands were powerful, though, full of veinous strength, the fingers gnarled and enormous.

“Nothin’ we can do,” continued Mr. Everhart. “We people of the common herd are to be seen but not heard. Let the big Money Bags start the wars, we’ll fight ’em and love it.” He lapsed into a malign silence.

“But I got a feelin’,” resumed the old man with his pouting smile, “that Bill’s just goin’ along for the fun. He’s not one you can fool, Billy ... and I guess he figures the merchant marine will do him some good, whether he takes only one trip or not. Add color to his cheeks, a little sea an’ sunshine. He’s been workin’ pretty hard all these years. Always a quiet little duck readin’ books by himself. When the woman died from Sonny, he was twenty-two, a senior in the College—hit him hard, but he managed. I was still workin’ at the shipyards, so I sent him on for more degrees. The daughter offered to move in with her husband an’ take care of little Sonny. When Billy finished his education—I always knew education was a good thing—I swear I wasn’t surprised when he hit off a job with the Columbia people here.”

Wesley nodded.

The father leaned forward anxiously in his chair.

“Billy’s not a one for the sort of thing he’s goin’ into now,” he said with a worried frown. “You look like a good strong boy, son, and you’ve been through all this business and know how to take care of yourself. I hope ... you keep an eye on Billy—you know what I mean—he’s not ...”

“Whatever I could do,” assured Wesley, “I’d sure all do it.” [...]

“Hell, man, we’ll bum to Boston,” said Wesley.

“Sure!” beamed the other. “Besides, I never hitchhiked before; it would be an experience.”

“Do we move?”

Everhart paused for a moment. What was he doing here in this room, this room he had known since childhood, this room he had wept in, had ruined his eyesight in, studying till dawn, this room into which his mother had often stolen to kiss an

d console him, what was he doing in this suddenly sad room, his foot on a packed suitcase and a traveler’s hat perched foolishly on the back of his head? Was he leaving it? He glanced at the old bed and suddenly realized that he would no longer sleep on that old downy mattress, long nights sleeping in safety. Was he forsaking this for some hard bunk on board a ship plowing through waters he had never hoped to see, a sea where ships and men were cheap and the submarine prowled like some hideous monster in DeQuincey’s dreams. The whole thing failed to focus in his mind; he proved unable to meet the terror which this sudden contrast brought to bear on his soul. Could it be he knew nothing of life’s great mysteries? Then what of the years spent interpreting the literatures of England and America for note-hungry classes? ... had he been talking through his hat, an utterly complacent and ignorant little pittypat who spouted the profound feelings of a Shakespeare, a Keats, a Milton, a Whitman, a Hawthorne, a Melville, a Thoreau, a Robinson as though he knew the terror, fear, agony, and vowing passion of their lives and was brother to them in the dark, deserted old moor of their minds?

Wesley waited while Everhart stood in indecision, patiently attending to his fingernails. He knew his companion was hesitating.

At this moment, however, Bill’s sister entered the room smoking a Fatima and still carrying her cup of tea. She and her friend, a middle-aged woman who now stood beaming in the doorway, had been engaged in passing the afternoon telling each other’s fortune’s in the tea leaves. Now the sister, a tall woman with a trace of oncoming middle age in her stern but youthful features, spoke reproachfully to her younger brother: “Bill, can’t I do anything to change your mind. This is all so silly? Where are you going, for God’s sake ... be sensible.”

“I’m only going on a vacation,” growled Bill in a hunted manner. “I’ll be back.” He picked up his bag and leaned to kiss her on the cheek.

[...]

CHAPTER FOUR

At three o’clock, they were standing at the side of the road near Bronx Park, where cars rushed past fanning hot clouds of dust into their faces. Bill sat on his suitcase while Wesley stood impassively selecting cars with his experienced eye and raising a thumb to them. Their first ride was no longer than a mile, but they were dropped at an advantageous point on the Boston Post Road.

The sun was so hot Bill suggested a respite; they went to a filling station and drank four bottles of Coca-Cola. Bill went behind to the washroom. From there he could see a field and a fringe of shrub steaming in the July sun. He was on his way! ... New fields, new roads, new hills were in store for him—and his destination was the seacoast of old New England. What was the strange new sensation [that] lurked in his heart, a fiery tingle to move on and discover anew the broad secrets of the world? He felt like a boy again ... Perhaps, too, he was acting a bit silly about the whole thing.

Back on the hot flank of the road, where the tar steamed its black fragrance, they hitched a ride almost immediately. The driver was a New York florist en route to his greenhouse near Portchester, N.Y. He talked volubly, a good-natured Jewish merchant with a flair for humility and humor: “A couple of wandering Jews!” he called them, smiling with a sly gleam in his pale blue eyes. He dropped them off a mile beyond his destination on the New York—Connecticut state line.

Bill and Wesley stood beside a rocky bed which had been cut neatly at the side of the highway. In the shimmering distance, Connecticut’s flat meadows stretched a pale green mat for sleeping trees.

Wesley took off his coat and hung it to a shoulder while Bill pushed his hat down over his eyes. They took turns sitting on the suitcase while the other leaned on the cliffside, proffering a lazy thumb. Great trucks labored up the hill, leaving behind a dancing shimmer of gasoline fumes.

“Next to the smell of salt water,” drawled Wesley with a grassblade in his mouth, “I’ll take the smell of a highway.” He spat quietly with his lips.

“Gasoline, tires, tar, and shrubbery,” added Bill lazily. “Whitman’s song of the open road, modern version.” They sunned quietly, without comment, in the sudden stillness. Down the road, a truck was shifting into second gear to start its uphill travails.

“Watch this,” said Wesley. “Pick up your suitcase and follow me.”

As the truck approached, now in first gear, Wesley waved at the driver and made as if to run alongside the slowly toiling behemoth. The driver, a colorful bandanna around his neck, waved a hand in acknowledgment. Wesley tore the suitcase from Bill’s hand and shouted: “Come on!” He dashed up to the truck and leaped onto the running board, shoving the suitcase into the cab and holding the door open, balanced on one foot, for Bill. The latter hung on to his hat and ran after the truck; Wesley gave him [a] hand as he plunged into the cab.

“Whoo!” cried Bill, taking off his hat. “That was a neat bit of Doug Fairbanks dash!” Wesley swung in beside him and slammed the door to. [...]

“Are you sure about that ship in Boston?”

“Yeah, ... the Westminster, transport-cargo, bound for Greenland; did you bring your birth-certificate, man?”

Everhart slapped his wallet; “Right with me.”

Wesley yawned again, pounding his breast as if to put a stop to his sleepiness. Everhart found himself wishing he were back home in his soft bed, with four hours yet to sleep before Sis’s breakfast, while the milkman went by down on Claremont Avenue and a trolley roared past on sleepy Broadway.

A drop of rain shattered on his brow.

“We’d best get a ride right soon!” muttered Wesley turning a gaze down the deserted road.

They took shelter beneath a tree while the rain began to patter softly on the overhead leaves; a wet, steamy aroma rose in a humid wave.

“Rain, rain go away,” Wesley sang softly, “come again another day...”

Ten minutes later, a big red truck picked them up. They smiled enthusiastically at the driver.

“How far you goin’, pal?” asked Wesley.

“Boston!” roared the driver, and for the next hundred and twenty miles, while they traveled through wet fields along glistening roads, past steaming pastures and small towns, through a funereal Worcester, down a splashing macadam highway leading directly toward Boston under lowering skies, the truckman said nothing further.

Everhart was startled from a nervous sleep when he heard Wesley’s voice ... hours had passed swiftly.

“Boston, man!”

He opened his eyes; they were rolling along a narrow, cobblestoned street, flanked on each side with grim warehouses. It had stopped raining.

“How long have I been sleeping?” grinned Bill, rubbing his eyes while he held the spectacles on his lap.

“Dunno,” answered Wesley, drawing from his perennial cigarette. The truck driver pulled to a lurching halt.

“Okay?” he shouted harshly.

Wesley nodded: “Thanks a million, buddy. We’ll be seeing you.”

“So long, boys,” he called. “See you again.”

Everhart jumped down from the high cab and stretched his legs luxuriously, waving his hand at the truck driver. Wesley stretched his arms slowly: “Eeyah! That was a long ride; I slept a bit meself.”

They stood on a narrow sidewalk, which had already begun to dry after the brief morning rain. Heavy trucks piled past in the street, rumbling on the ancestral cobblestones, and it wasn’t until a group of them had gone, leaving the street momentarily deserted and clear of exhaust fumes, that Bill detected a clean sea smell in the air. Above, broken clouds scuttled across the luminous silver skies; a ray of warmth had begun to drop from the part of the sky where a vague dazzle hinted the position of the sun.

“I’ve been to Boston before,” chatted Bill, “but never like this ... this is the real Boston.”

Wesley’s face lit in a silent laugh: “I think you’re talkin’ through your hat again, man! Let’s start the day off with a beer in Scollay Square.”

They walked on in high spirits.

Scollay Square was a short five minutes away. Its

subway entrances, movie marquees, cut-rate stores, passport photo studios, lunchrooms, cheap jewelry stores, and bars faced the busy traffic of the street with a vapid morning sullenness. Scores of sailors in Navy whites sauntered along the cluttered pavements, stopping to gaze at cheap store fronts and theater signs.

Wesley led Bill to a passport photo studio where an old man charged them a dollar for two small photos.

“They’re for your seaman’s papers,” explained Wesley. “How much money does that leave you?”

“A quarter,” Everhart grinned sheepishly.

“Two beers and a cigar; let’s go,” Wesley said, rubbing his hands. “I’ll borrow a fin from a seaman.”

Everhart looked at his pictures: “Don’t you think I look like a tough seadog here?”

“Hell, man, yes!” cried Wesley.

In the bar they drank a bracing glass of cold beer and talked about Polly, Day, Ginger, and Eve.

“Nice bunch of kids,” said Wesley slowly.

Everhart gazed thoughtfully at the bartop: “I’m wondering how long Polly waited for us last night. I’ll bet this is the first time Madame Butterfly was ever stood up,” he added with a grin. “Polly’s quite the belle around Columbia, you know.” It sounded strange to say “Columbia” ... how far away was it now? [...]

“Well! We’re in Boston,” beamed Bill when they were back on the street. “What’s on the docket?”

“First thing to do,” said Wesley, leading his companion across the street, “is to mosey over to the Union Hall and check up on the Westminster ... we might get a berth right off.”

They walked down Hanover street, with its cheap shoe stores and bauble shops, and turned left at Portland street; a battered door, bearing the inscription “National Maritime Union,” led up a flight of creaking steps into a wide, rambling hall. Grimy windows at each end served to allow a gray light from outside to creep inward, a gloomy, half-hearted illumination which outlined the bare, unfurnished immensity of the room. Only a few benches and folding chairs had been pushed against the walls, and these were now occupied by seamen who sat talking in low tones: they were dressed in various civilian clothing, but Everhart instantly recognized them as seamen ... there, in the dismal gloom of their musty-smelling shipping headquarters, these men sat, each with the patience and passive quiet of men who know they are going back to sea, some smoking pipes, others calmly perusing the “Pilot,” official N.M.U. publication, others dozing on the benches, and all possessed of the serene, waiting wisdom of a Wesley Martin.

Tristessa

Tristessa On the Road

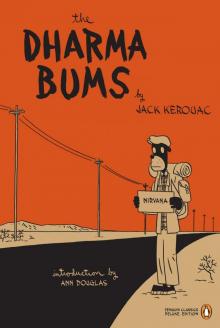

On the Road The Dharma Bums

The Dharma Bums Maggie Cassidy

Maggie Cassidy Big Sur

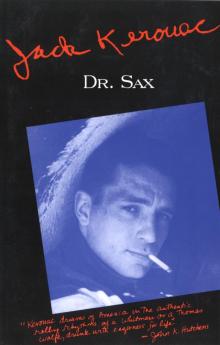

Big Sur Dr. Sax

Dr. Sax Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46

Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46 The Sea Is My Brother

The Sea Is My Brother The Town and the City: A Novel

The Town and the City: A Novel Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Desolation Angels: A Novel

Desolation Angels: A Novel Book of Sketches

Book of Sketches Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha

Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha The Electrocution of Block 38383939383

The Electrocution of Block 38383939383 Haunted Life

Haunted Life Visions of Gerard

Visions of Gerard Orpheus Emerged

Orpheus Emerged Book of Blues

Book of Blues The Subterraneans

The Subterraneans The Haunted Life

The Haunted Life The Unknown Kerouac

The Unknown Kerouac The Town and the City

The Town and the City Visions of Cody

Visions of Cody Atop an Underwood

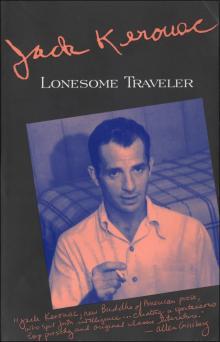

Atop an Underwood Lonesome Traveler

Lonesome Traveler Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg Vanity of Duluoz

Vanity of Duluoz Desolation Angels

Desolation Angels On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition)

On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition) The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel

The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel Wake Up

Wake Up The Poetry of Jack Kerouac

The Poetry of Jack Kerouac Doctor Sax

Doctor Sax