- Home

- Jack Kerouac

Vanity of Duluoz Page 3

Vanity of Duluoz Read online

Page 3

Not only that, but that winter I was high scorer on the Lowell High track team and even had time to have my first love affair with Maggie Cassidy, said story recorded in novel of same name in detail.

Being a football and track star, a highgrade scholar, independent, nutty with independence in fact so that when blizzards broke out in Lowell it was only I by myself and nobody in sight out there in the woods of Dracut hiking kneedeep with a hockey stick, just to get an appetite for Sunday dinner and to pause under pines to hear the crazy crows go ‘Yak’. Being also goodlooking and strong I’m sure a lot of people hated my guts then, even you, wifey, when you let slip last fall ‘Well I was never popular like you were.’ Fact was, I wasnt popular at all but hated by most, really, after all that’s going a little too far, trying to outdo everybody in everything except of course being invited to the Girl Officers’ Ball and having my picture on the society page. Time enough for that, even, ha ha, as if I cared, or care now. That was vanity too, including that last remark, to make such an effort to cut everybody down. You’ll be glad to know I got my comeuppance, so dont worry.

The next step was to pick a college. My mother insisted on Columbia because she eventually wanted to move there to New York City and see the big town. My father wanted me to go to Boston College because his employers, Callahan Printers of Lowell, were promising him a promotion if he could persuade me to go there and play under Francis Fahey. They also hinted he’d be fired if I went to any other college. Fahey, as I say, was at the house, and I have in my possession today a postcard he wrote Callahan saying: ‘Get Jack to Boston College at all costs.’ (More or less.) But I wanted to go to New York City too and see the big town, what on earth was I expected to learn from Newton Heights or South Bend Indiana on Saturday nights and besides I’d seen so many movies about New York I was . . . well no need to go into that, the waterfront, Central Park, Fifth Avenue, Don Ameche on the sidewalk, Hedy Lamar on my arm at the Ritz. I agreed my mother was right as usual. She not only told me to leave Maggie Cassidy at home and go on to New York to school, but rushed to McQuade’s and bought big sports jacket and ties and shirts out of her pitiful shoeshop savings that she kept in her corset, and arranged for me to board with her stepmother in Brooklyn in a nice big room with high ceiling and privacy so I could study and make good grades and get my sleep for the big football games. There were big arguments in the kitchen. My father was fired. He went downtrodden to work in places out of town, always riding sooty old trains back to Lowell on weekends. His only happiness in life now, in a way, considering the hissing old radiators in old cockroach hotel rooms in New England in the winter, was that I make good and justify him anyway.

That he was fired is of course a scandal and something about Callahan Printers I havent forgotten and is another black plume in my hat of ‘success’. For after all what is success? You kill yourself and a few others to get to the top of your profession, so to speak, so that when you reach middle age or a little later you can stay home and cultivate your own garden in bliss: but by that time, because you’ve invented some kind of better mousetrap, mobs come rushing across your garden and trampling all your flowers. What’s with that?

II

First, Columbia arranged to have me go to prep school in New York to make up credits in math and French, subjects overlooked by myself at Lowell High School. Big deal, I couldnt speak anything but French till I was six, so naturally I was in for an A right there. Math was basic, a Canuck can always count. The prep school was really an advanced high school called Horace Mann School for Boys, founded I s’pose by odd old Horace Mann, and a fine school it was, with ivy on granite walls, swards, running tracks, tennis courts, gyms, jolly principals and teachers, all on a high hill overlooking Van Cortlandt Park in New York City upper Manhattan. Well, since you’ve never been there why bother with the details except to say, it was at 246th Street in New York City and I was living with my stepgrandmother in Brooklyn New York, a daily trip of two hours and a half by subway each way.

Nothing deters young punk kids, not even today, here’s how I managed it: a typical day:

First evening before first day of school I’m sitting at my large table set in the middle of my high-ceilinged room, stately erect in the chair with pen in hand, books ranged before me and held up by noble bronze bookends found in the cellar. It is completely formal beginning of my search for success. I write: ‘Journal. Fall, 1939. Sept 21. My name is John L. Duluoz, regardless of how little that may matter to the casual reader. However, I find it necessary to give some pretense of explanation for the material existence of this Journal’ and other such schoolboy stuff, followed by ‘And I will give some sort of apology for using pen and ink.’ (‘Harrumph!’ I’m thinking. ‘Egad! Zounds, Pemberbroke!’) And then I add in ink: ‘It seems that such men as Thackeray, Johnson, Dickens, and others had to compile vast volumes in pen and ink, and despite the fact that I not modestly admit some degree of proficiency in typewriting, I feel that I should not proceed in my literary ventures with such ease as would befit a typewriter. I feel that a recurrence to the old method would sort of leave a silent tribute to those old gladiators, those immortal souls of journalism. Stay! I am not in any way suggesting that I am included in their fold, but that what was good enough for them, should by ail means suit me.’

This done, I go downstairs to the basement where my great-stepmother Aunt Ti Ma has fixed up her place like a combination of gypsy with drapes and hanging beads in doorways, and lace doilies Victorian style, a thousand dolls, comfort, beautiful, clean, neat chairs, reading her paper, big fat happy Ti Ma. Her husband is Nick the Greek, Evengelakis, whom she met and married in Nashua NH after the death of my own mother’s Pa. Her daughter Yvonne, blue-eyed, companion of her mother, married to Joey Robert who comes home every night at eleven with the Daily News from a trucking warehouse job and gets in his T-shirt at the kitchen table and reads. Down there they have for me all the time great vast glasses of milk and beautiful Sand Tart cakes from Cushman’s of Brooklyn. They say ‘Go to bed early now, Jacky, school and practice tomorrow. You know what your Mama said, gotta make good.’ But before I go to bed, full of cake and ice cream, I make my lunch for the next day: always the same: I butter one sandwich plain and the other peanut butter and jam, and throw in a fruit, either apple or banana, and wrap it up nice and put it in bag. Then Nick, Uncle Nick, takes me by the arm and says: ‘When you have more time I tell you some more about Father Coughlin. If you want some more books, there are many more in the cellar. Look this one.’ He hands me a dusty old Jules Romain novel called Ecstasy, no I think it was Rapture. I take it upstairs and add it to my library. My room is separated from Aunt Yvonne’s by nothing but a huge double glass door but the gypsy drapes are there. My own room has a disusable marble fireplace, a little sink in an alcove, and a huge bed. Out the vast Brooklyn Thomas Wolfe windows I see exactly what Wolfe always saw, even in that very month: old red light falling on Brooklyn warehouse windows where men lean out on sills in undershirts chewing on toothpicks while taking a break.

I set up my neatly pressed pants, sports jacket, schoolbooks, shoes in place together neatly, socks over that, wash and go to bed. I set the alarm clock for, listen to this, 6 A.M.

At 6 A.M. I groan and get out, wash, dress, go downstairs, take that lunchbag and rush out into the pippin red nippy streets of Brooklyn and go three blocks to the IRT subway at the El on Fulton Street. Down I go and push into the subway with hundreds of people carrying newspapers and lunchbags. I stand all the way to Times Square, threequarters solid hour, every blessed morning. But what does young dughead do about it? I whip out my math book and do all me homework while standing, lunch between feet. I always find a corner where I can sorta guard my lunch between feet and where I can lean and turn and study with face to lurching car wall. What a stink in there, of hundreds of mouths breathing and no air coming in; the sickening perfume of women; the well-known garlic breath of Old New York; old men cou

ghing and secretly spitting between their feet Who lived through it?

Everybody.

By the time we’re at Times Square, or maybe Penn Station at 34th just before that, most people rush out, to midtown work, and Ah, I get the usual corner seat and start in on the physics studies. Now it’s easy sailing. At 72nd Street we pick up another slue of workers headed for uptown Manhattan and Bronx work but I dont care anymore: I’ve got a seat. I turn to the French book and read all those funny French words we never speak in Canadian French, I have to consult and look them up in the glossary in back, I think with anticipation how Professor Carton of French class will laugh at my accent this morning as he asks me to get up and read a spate of prose. The other kids however read French like Spanish cows and he actually uses me to teach them the true accent. Now you’d think I’m close to school but from 96th Street we go past Columbia College, we go into Harlem, past Harlem, way up, another hour, till the subway emerges from the tunnel (as tho by nature it was impossible for it to go underground so long) and goes soaring to the very end of the line in Yonkers practically.

Near school? No, because there I have to go down the elevated steps and then start up a steep hill about as steep as 45 degrees or a little less, a tremendous climb. By now all the other kids are with me, puffing, blowing steam of morning, so that from 6 A.M. when I got up in Brooklyn, till now, 8.30, it’s been two and a half hours of negotiating my way to actual class. A chore I found a thousand times more difficult than when we used to walk that mile and a half to Bartlett Junior High School from Pawtucketville and Rosemont.

III

I dont understand why, except it must be an exceptional school; but 96 percent of the students are Jewish kids, and most of them are very rich: sons of furriers, famous realtors, thissa and thatta and here come mobs of them in big black limousines driven by chauffeurs in visored hats, carrying large lunchboxes full of turkey sandwiches and Napoleons and chocolate milk in thermos bottles. Some of them, like students of the first form, are only ten years old and 4 feet tall; some of them are funny little fat tubs of lard, I guess because they didnt have to climb that hill. But most of the rich Jewish kids took the subway from apartments on Central Park West, Park Avenue, Riverside Drive. The other 4 percent or so of the students were from prominent Irish and other families, such as Mike Hennessey whose father was the basketball coach of Columbia, or Bing Rohr a German boy whose father had been a big contractor connected with building the gym. Then came the 1 percent to which I belonged, called ringers, B or A average students who were also athletes, from all over, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Pennsy, who had been given partial financial scholarship arrangements to come to Horace Mann, get their credits for college, and make the joint the Number One high school football team in New York City, which we did that year.

But first, 8.45 or so, we all had to sit in the auditorium and be led in the singing of ‘Onward Christian Soldiers’ by English Professor Christopher Smart, followed by ‘Lord Jeffrey Amherst’ which was a song no more appropriate for me to sing (as descendant of French and Indian) than it was appropriate for the Jewish kids to sing ‘Onward Christian Soldiers’. It was fun no les.

Then the classes began. History class with Professor Albert which bored me because this was the only classroom that faced east-northeast across the dim trees of Van Cortlandt Park and therefore faced toward Lowell, in fact the trees had the dim Indian look of Massachusetts trees, so I sat there not really listening to Albert and pondering my own history: Maggie Cassidy foremost, as would all seventeen-year-old kid reveries, but also my Pa, proud by now, my Ma (at the very moment seeing that my typewriter was being mailed and would arrive that very afternoon in Brooklyn, for instance), and my sister. A welling of tears almost to remember the boyhood friends waiting back there for me. Had the idea history would never interest me anyway, and besides Professor Albert was dull on the subject, accurate yes, I s’pose, but history is best explained dramatically, because for God’s sake nobody’s going to tell me that massive Homeric War so to speak, between the Achaeans and the Iliums was caused merely by some economic factor concerning trade, what about the trade in Helen’s chastity belt? Or the belt in the eye Paris was about to get from Philoctetes? Anyway, this was the class that I spent mooning and viewing the window vistas especially on cloudy days when the trees held that sad New England non-New Yorkish deep gray knighthood look. Directly across the hall it was then physics class with sprightly little Billy Wine explaining Archimedes’ bathtub, or Ohm’s law which I never could figure, where in fact I was really the dunce of the class but caught on later and made a fair mark (B-minus). I’d never fiddled with the mechanics of an auto, for instance, like all the other football players in the class; they laughed at me because I didn’t know the essentials of a battery. I was about to show em a battery out on the field.

Next class was English with Professor Christopher Smart; now what better name should your English teacher have unless it be William Blake or Robert Herrick or Lord Geoffrey Chaucer? And from him I always got an A-plus, old Joe Maple of Lowell High School had done me well teaching to appreciate not only Walt Whitman but Emily Dickinson and letting the other kids moon over Ernest Henley’s ‘My head is bloody, but unbowed’. In English class it developed that I had to write a half-dozen term papers for some of the wealthy Jewish kids, at two dollars a throw, and for the football ringers for free or else. Easy, with my typewriter in my Brooklyn quarters. You may say this was bad but what about Deni Bleu selling daggers behind the lockers to little tubby kids for a fin?

Lunch was where everybody removed their lunchbags from their lockers and rushed into the cafeteria type diningroom to grab the milk or soft drinks or coffee. Here I ate my humble awful lunch among fragrant turkey sandwiches, it wasnt the first time I was about to eat worse than everybody in sight, and later, with success assured at last, as they say, lost my appetite anyway. Sometimes a rich kid would give me a delicious fresh juicy chicken sandwich, ah wow, especially Jonathan Miller who got to really like me and was the first to invite me home for dinner and finally for whole weekends where, on Friday mornings, say, after some holiday dance, his rich Wall Street financier father would get up and sit at a grand mahogany table in the diningroom, in this seventeenth-floor apartment on West End Avenue right across from the Schwab Mansion (still standing then), and out of the kitchen would come out a sweet Negro butler bringing him his grapefruit. Which the old man would proceed to dig into with a spoon, and just like in the movies the spurt of grapefruit juice would hit me in the eye across the tablecloth. Then he’d have one simple softboiled egg in an eggcup, neatly whack it, eat out of it with a silver spoon, adjust his spectacles, say over the New York Times to his son Jonathan: ‘Jonathan, why arent you like your friend Jack here? He is, as we say in Latin, mens sana et mens corpora, healthy mind and healthy body. He combines all the excellence of a Greek, that is, the brain of an Athenian and the brawn of a Spartan. And you, look at you.’ This was awful. Because poor old Jonathan was the first guy to get me interested in formal literature apart from the Sherlock Holmes interests I’d had so far in my kid compositions, got me to understand Hemingway and try to write like him, and showed me a thing or two round town later in the way of avant-garde movies, and manners, and mores, and Dixieland jazz. Anyway sometimes at lunch, seeing my awful peanut butter sandwiches, he’d offer me some of his chicken sandwiches beautifully prepared by his maid, and the football team would guffaw. I was not popular with the other members of the football team because they thought I was hanging around with the nonathletic Jewish kids and snubbing the athletes, for sandwiches, favors, dinners, two-dollar term papers, and they were right I guess. But I was fascinated by Jewish kids because I’d never met any in my life, especially these well-bred, rather fawncy dressers, tho they all had the ugliest faces I ever saw and awful pimples. I had pimples too, tho.

Sometimes lunch, in good weather, would then spill out into the green lawns and we’d

all stand around having soft drinks in the sun, if it was a snow thaw there’d be snowball fights and snowballs thrown against the Tom Brown plaque on the ivied walls that said: ‘Horace Mann School for Boys’. It’s only today I found out Horace Mann’s son once went on a trip to Minnesota with Henry David Thoreau, a neighbor of mine at Walden Pond near Concord, trees of which I can see on clear days from this present upstairs bedroom where I’m writing this Vanity of Duluoz.

IV

After lunch it was the French class, mentioned before, Professor Carton of Georgia actually a sickly but sweet old Southerner who liked me and wrote letters to me later and I think was a bit on the gay side, in the best sense. In this class I got to sit next to Lionel Smart, who became my really best friend, Liverpool Jew of some sort from London whose father, a renowned chemist, had sent him and brother and mother to the United States to avoid the London blitz: also rich: but who taught me jazz by taking me down to the Apollo Theater in Harlem after the football season where we sat in the front row and had our eyes and ears blasted out by the full great Jimmie Lunceford band and later Count Basie.

He was funny, Lionel. In the following class, math, he was called ‘Nutso’ by Professor Kerwick. Professor Kerwick says: ‘Now boys, smart are ye? I’ll give you a number series and I want you to tell me what the relation is’ (or words to that effect, I’m no calculus-izer). He said: ‘Are you ready? Here it is: 14, 34, 42, 72, 96, 103, 110, 116, 125.’ Nobody could figure out but it rang a strange familiar tune in my noodle and I almost was about to jump up and announce what it ‘sounded’ like at least but was afraid of our football quarterback, Biff Quinlan, who kept giving me wry looks because I hung around with Lionel and Jonathan Miller and the other Jewish kids instead of him and his bunch of thugs you might say (today Biff however is beloved respected old football coach at Horace Mann School for Boys, so of course he was no thug, nobody was), but I was afraid of being laughed at. As for Nutso everybody laughed at him anyway. ‘All right, Nutso Smart, get up and tell me what that is.’

Tristessa

Tristessa On the Road

On the Road The Dharma Bums

The Dharma Bums Maggie Cassidy

Maggie Cassidy Big Sur

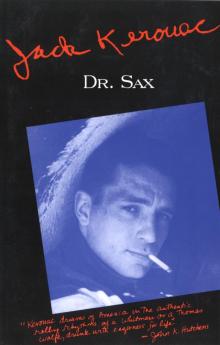

Big Sur Dr. Sax

Dr. Sax Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46

Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46 The Sea Is My Brother

The Sea Is My Brother The Town and the City: A Novel

The Town and the City: A Novel Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Desolation Angels: A Novel

Desolation Angels: A Novel Book of Sketches

Book of Sketches Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha

Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha The Electrocution of Block 38383939383

The Electrocution of Block 38383939383 Haunted Life

Haunted Life Visions of Gerard

Visions of Gerard Orpheus Emerged

Orpheus Emerged Book of Blues

Book of Blues The Subterraneans

The Subterraneans The Haunted Life

The Haunted Life The Unknown Kerouac

The Unknown Kerouac The Town and the City

The Town and the City Visions of Cody

Visions of Cody Atop an Underwood

Atop an Underwood Lonesome Traveler

Lonesome Traveler Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg Vanity of Duluoz

Vanity of Duluoz Desolation Angels

Desolation Angels On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition)

On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition) The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel

The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel Wake Up

Wake Up The Poetry of Jack Kerouac

The Poetry of Jack Kerouac Doctor Sax

Doctor Sax