- Home

- Jack Kerouac

Visions of Cody Page 3

Visions of Cody Read online

Page 3

* * *

POUGHKEEPSIE BACKYARDS on a clear, keen, painfully blue late October day—with the sky looking like it had been sugar cured, peppered and cloved and smoked during the night like a ham and was retaining hints of glistening moisture in the skin—somewhere in its pigmentation. The town of Poke, and the backyards with wash hung out as far as the eye can see because the lovely simple apple pie wives (like Cody’s wife in rickety Frisco same) with short dresses and sexy bare legs just naturally have agreed that Monday is Washday—so there’s a silence in the mystic rippling clotheslines right now, gardens of silence in the backyards—here and there you see a garage with the door open and splintered shelves of oil cans inside—a housewife in a housecoat shaking out her dry mop with dreamy irritation—three more of them going by with groceries and wondering who the fuck is sitting on mad McCarthy’s porch—The silent backyards make you think of the men who are working with their hands and left things in order during the day, left their wives to do chores that on an afternoon like this (towels flapping in unison down the block) is symbolic—the sheets of the night are aired to Monday rumors—it is advertised to the Lord in the sunny heaven that women live here and the earth is taken care of—dusk will bring the men back, slamming along the walls to be let in, rolling home on clattering rollerskates to occupy (in a blind dream) the houses that sat all day breathing and waiting for them—little children, meanwhile, who own the secret porches, fall adreaming on the swirl of clotheslines, Arctic, sad.

Far off, like seeing a new nation of monkeys in the trees across the river (no river, just a rill of gardens) are levels and continents of wash hung out by treedwellers and seven-foot women: this is an Africa that you find in the middle of a drowsy American day—Over there, nearer, they’ve arrived jiggling all over with curiosity, the little fallen sparrows—asking themselves questions—swish, they’re gone.

* * *

I REMEMBER CODY, awed telling me, the last time he ever came to New York, of knock on the door lasting a half hour at Josephine’s, his going down fire escape backlot, landlord who’d bought the damned ground threw open his window and said “Yes, what is it?” and Cody said “You wouldn’t think a friendly looking fellow like me, and believe me I am a friendly nice fellow, would be and even though it’s strange for me to say it openly and to a stranger—but I’m not a robber—look at me, just look at me, I assure you.”

It’s like when I’m looking through Wilson’s bookshelf and start humming a tune while he’s arguing with Marian—(“Moonglow”). “What made you think of singing that?”

“I dunno.”

“It’ll forever be a mystery to me—”

No possible way of avoiding enigmas. Like people in cafeterias smile when they’re arriving and sitting down at the table but when they’re leaving, when in unison their chairs scrape back they pick up their coats and things with glum faces (all of them the same degree of semi-glumness which is a special glumness that is disappointed that the promise of the first-arriving smiling moment didn’t come out or if it did it died after a short life)—and during that short life which has the same blind unconscious quality as the orgasm, everything is happening to all their souls—this is the GO—the summation pinnacle possible in human relationships—lasts a second—the vibratory message is on—yet it’s not so mystic either, it’s love and sympathy in a flash. Similarly we who make the mad night all the way (four-way sex orgies, three-day conversations, uninterrupted transcontinental drives) have that momentary glumness that advertises the need for sleep—reminds us it is possible to stop all this—more so reminds us that the moment is ungraspable, is already gone and if we sleep we can call it up again mixing it with unlimited other beautiful combinations—shuffle the old file cards of the soul in demented hallucinated sleep—So the people in the cafeteria have that look but only until their hats and things are picked up, because the glumness is also a signal they send one another, a kind of a “Goodnight Ladies” of perhaps interior heart politeness. What kind of friend would grin openly in the faces of his friends when it’s the time for glum coatpicking and bending to leave? So it’s a sign of “Now we’re leaving this table which had promised so much—this is our obsequy to the sad.” The glumness goes as soon as someone says something and they head for the door—laughing they fling back echoes to the scene of their human disaster—they go off down the street in the new air provided by the world.

Ah the mad hearts of all of us.

* * *

THE MAN READING THE PAPER before the big green door is like an Arab in city clothing, felt hat, bow tie, plaid pants, like Aly Khan he has black hair bulging from the sides under his hat—He sits semi-facing cafeteria (where us Egyptians wait) under this damn twenty-foot door that looks like it’s going to open behind him and a green monstrous five-foot hand will come out, wrap around his chair and slide him in, the great door swinging back shut and no one noticing. (And on each side of the great door is a green pillar!) Inside, that man will be made naked and humiliated—but actually gladdened—he’s shaking his head sadly at the paper—he’s moving his foot up and down nervously as he reads—he’s jutting up his lower lip, deep in reading—but the way he holds the paper vertically folded and now bending it over like a little woman to follow the print you can see his mind’s really goofing—and he’s waiting for something else. The big green door holds itself up like a lamb to sacrifice to the sun at sea dawn over him, and it has wings.

An immense plate glass window in this white cafeteria on a cold November evening in New York faces the street (Sixth Avenue) but with inside neon tubular lights reflected in the window and they in turn illuminating the Japanese garden walls which are therefore also reflected and hang in the street with the tubular neons (and with other things illuminated and reflected such as that enormous twenty-foot green door with its red and white exit sign reflected near the drapes to the left, a mirror pillar from deep inside, vaguely the white plumbing and at the top of things upper right hand and the signs that are low in the window looking out, that say Vegetarian Plate 60¢, Fish Cakes with Spaghetti, Bread and Butter (no price) and are also reflected and hanging but only low on the sidewalk because also they’re practically against it)—so that a great scene of New York at night with cars and cabs and people rushing by and Amusement Center, Bookstore, Leo’s Clothing, Printing, and Ward’s Hamburger and all of it November clear and dark is riddled by these diaphanous hanging neons, Japanese walls, door, exit signs—

But now let’s examine it closer. Riddled and penetrated and obscured and rippled and haunted and of course like kaleidoscope over kaleidoscope but above the glittering street are the darkened or brown-lit windows of Sixth Avenue semi-flophouses and beat doll shops and blackdust plumbing shops and Waldorf Cafeteria Employment Office closed, red neons through windows at other end—Furthest up in dark is the focus of this entire human scene: this is a fourth floor unwashed window with the shade not drawn more than a foot but ever so thin brown filthy lace or muslin curtain (and now the light went off!!) failing to hide the shadow of an iron bed. Now that it’s gone off the mirror pillar is suddenly revealed all the way to its entire length because my attention had been on the actual window and the reflected pillar was just barely touching the edge of the window and I didn’t know it. Most amazing of all now this reflected mirror pillar hanging in the street is at the same time reflecting the tubular neon, the real one inside, not the imaged one outside, and also reflects parts of the wall I didn’t mention that are not Japanese but checked red and green. There are no more lights in those windows up there, I’ll tell you what happened: some old man finished his last quart of beer and went to sleep—either that or he was hungry, wanted to sleep it off instead of spending fifty-five cents for fishcakes at Automat—or an old whore fell weeping on her bed of darkness—or they saw me noticing the window four stories and across the street down the mad city night—or now that the light is off they can see me better across all these confusions of reflected light (I know now th

at paranoia is the vision of what’s happening and psychosis is the hallucinated vision of what’s happening, that paranoia is reality, that paranoia is the content of things, that paranoia’s never satisfied). Other signs, the window ones, are reflected this way:

(put a mirror to it) and across this goofiness cars flash by and the asses of pedestrians hurrying in the cold flash by, when it’s yellow cabs the flash is brilliant yellow streak, when people the flash is memoried and human (a hand, a bag, a burden, a coat, a package of canvases, a dull, above it the floating white faces)—When it’s a car the flash is dark and shiny and staring into it for all signs of flashes sometimes you only see soft clicking oncoming and out going of glow from neon lights intertwined in the street—and the white line in the middle of Sixth Avenue, and just the barest indication of a piece of litter in the gutter across the street unless just the gutter’s reminder, without looking but just absorbing as you stare the people pass and you know what they are (two Texans! I knew it! and two Negroes! I knew it!) a beat gray coupe flashed through looking like something from Massachusetts (eager Canadians come to fuck in New York hotels)—now the backward Hot Chocolate Delicious letters are shifting their depths as my eyes rounden—they dance—through them I know the city, and the universe—Now and finally right next to this part of the plate glass window that I’ve been staring at for half an hour, peeking through an area of six inches between the drapes and the window is a sidewall mirror which is reflecting everything that’s happening to the right of me up the street, in fact to places I can’t even see, so that while staring into my “flasher” I suddenly saw a cab coming out of the corner of my eye and it just never arrived, just disappeared—it was coming from the right in actuality, in reflection from the left, and I had been watching the flash of actual rightward going cars and cabs—In that six-inch area also are the people, observing the same laws of movement and reflection but from not so great a distance because they are closer to the plate glass, specifically closer to the miraculous mirror, and aren’t outflung in the road appearing from far off. While observing this “flasher” a car came and parked in it, that is, a very shiny new fender is seen (obscuring, for instance, the white line in middle of road) and in that fender that’s round those crazy little images of things and light seen on round shinies (like when your nose hugens as you look closer) those little images but too small for me to observe in detail from a distance are playing—they’re playing only because a red neon is flashing and every time it’s on I see more of them than otherwise—and actually the main neon crazy image is playing on the silver rim of a headlamp of an Oldsmobile 88 (as I look and see now) as it flashes on and off red, and I hear above the clatter and sleepiness of cafeteria dishes (and swish of revolving door with flapping rubbers) and voices moaning, I hear above this the faint klaxons and moving rushes of the city and I have my great immortal metropolitan in-the-city feeling that I first dug (and all of us) as an infant…smack in the heart of shiny glitters.

* * *

ROAMING THOSE SUBWAYS I see a Negro cat wearing an ordinary gray felt hat but a deep blue, or purplish shirt with white shiny pearl-type buttons—a gray sharkskin suit jacket over it—but brown pants, black shoes, deep blue ordinary one-stripe socks and gabardine topper short and beat, with edgebottoms rain-raveled—carrying brown paper bag—his face (he’s sleeping) is big powerful fighter’s sullen thicklipped (thick Afric lip) but strangely pudgy sweet face—dark brownskin—his big hands hang, his fingernails are pink (not white) and are soiled from a laboring job—Looks like Joe Louis only a Joe Louis who has known nothing but the freezing cold Harlem winter mornings when old black-bumbs infinitely beater than old Cody Pomeray of wino Denver go by with wool caps pulled over their ears with no prospects for the future whatever except below zero filthy snows—His look is wild, frightened, almost tearful as he wakes from a nap and looks across aisle at redfaced white man in glasses and gray clothes with a big red ruby on his finger, as if that man wanted to kill him especially…(in fact man has eyes closed and chews gum). Now cat has seen me and looks at me with a kind of dawning simple interest but falls right back to sleep (people have watched him before).

This cat is coming from a job in Queens where undoubtedly there is a wire fence and he carries some kind of mop and goes about bareheaded. Now his big Harlem hat is on again (did I say ordinary? It has that wild level-swooping Harlem sharpness worked in, an Eastern hat, thousands of cats in the street). He makes me think too of that strange Negro gurgle or burble in the voice that goes with the strangely humble clownish position of the American Negro and which he himself needs and wants because of a primarily meek Myshkin-like saintliness mixed with the primitive anger in their blood. When he left he walk-waddled out, from side to side, clicking, lazy, half asleep, “What you doin? what you doin?” it, and he, seemed to say to me—Damn, now he gone, he gone, I love him.

But now let’s examine these American fools who want to be big burpers and ride in the subway with starched white collars (Oh G. J., your abyss?) and “business” clothes and yet by God they laugh and strain eagerly to their friends just like happy Codys, Leos, Charley Bissonnettes of time—this one’s a small businessman, actually a good guy I can tell by his pleading laugh—the kind that chokes and says “Oh yes say it again, I loved you that time!” And woe! woe! upon me, now I see he’s a cripple—left foot—and his face is the face now of a serious frowning eager invalid maybe like the face of that rollerboard monster on Larimer Street who must have turned it huge and eager from his bottoms when he saw him, young Cody, come ball-bouncing down the street from school in a slant of tragic lost afternoons long departed from the memory of love, which is the secret of America—lost too, this subway invalid, in the folds of his own thick bustling manlike neck muscles—carrying a paper file envelope—chatting with tall younger fellow in glasses whom he admires and to whom he leans of course with that love of older man for younger man and especially of sick man for healthy dumbman everywhere.

* * *

CLOSER TO HOME, IN JAMAICA, still wandering, a lovely bakery window: cherry pie with little round hole in the middle to show glazed cherries—same with all crust pies, including mince, apple—fruit cakes with cherries, nuts, glazed pineapple sitting in erect paper cups—wonderful custard pies with their golden moons—powdered lemon-filling layer cakes—little extraspecial cookies two-toned—also two-toned chocolate icings on round beautiful chocolate cakes with sprinklings of brown crumbs around bottom edges and lovely raveled arrangements in icing itself—done with baker’s trowels—Those fat scrumptious apple-pineapple cakes that look like bigger editions of Automat-cakes, lumpy icing with a glaze—Everybody’s watching—Wild raggedy coconut cakes with a cherry in the middle…like wild white hair.

The traceries of a tree against the gray rainy dusk—

It gave me a shudder of joy to see a cake with pink icing on top all raveled, with a red cherry in the middle, the sides around all covered with chocolate chip!

But across the street a bleak rectory. On the lawn in front are two twenty-foot spruce trees—the building is that peculiarly pale orange brick, color of puke, cat’s puke—done up English style, or Saxon, with fort ramparts over the door, the oaken door but pale brown oaken not dark with three little glazed windows on top for decoration and one in middle for the purpose of looking to see who’s coming in—on each side of gray concrete frame to all this with the carved oldprint word Rectory are jolly Charles Dickens English lamps—then two little narrow slit windows about a foot wide, four foot down—at base of this bunched entrance is cellar-window behind concrete protective curb of some kind (nameless, crazy, like the Christmas tree shrubberies in front of suburban law offices and the little wire fences around shrubs, shape:

all crazy, useless, supported by one-foot tall fenceposts made of iron but look as if taped, with a noose on top

with a curb to separate this, elevate, or emphasize its elevation from sidewalk and something never used or understood by anybody except t

hose incurable sitters like me and Cody)—

Above castle ramparts and Gothic windows of rectory front is a brick gable with a regular American window that has Venetian blind, above that a gray concrete cross that looks like the stanchions you see around war memorials in parks in the South and like crosses on cemetery main offices. Warm rich orange lights burn in rectory at dusk. This is certainly nothing like Proust’s Combray Cathedral, where the stone moved in eccentric waves, the cathedral itself a great refractor of light from “outside”—

THE POOR LONELY OLD LADIES OF LOWELL who come out of the five-and-ten with their umbrellas open for the rain but look so scared and in genuine distress not the distress of secretly smiling maids in the rain who have good legs to hop around, the old ladies have piano legs and have to waddle to their where-to—and talking about their daughters anyway in the middle of their distress.

People going by. The big cowlick Irishman with camel’s hair belted coat who lumbers along, his lips loosened in some sullen thought and as though it wasn’t raining in his huge dry soul—

The fat old lady incredible-burdened not only with umbrellas and rain cape but underneath bulging pregnantly with hidden protected packages that stick so far out she has trouble avoiding bumping people on sidewalk and when she gets in the bus it will create a major problem for the poor people who are now, in their own parts of the city headed for the bus, unsuspecting of this—

Tristessa

Tristessa On the Road

On the Road The Dharma Bums

The Dharma Bums Maggie Cassidy

Maggie Cassidy Big Sur

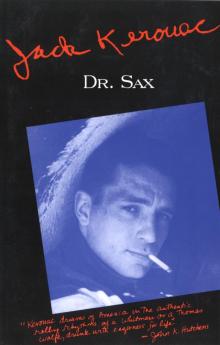

Big Sur Dr. Sax

Dr. Sax Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46

Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46 The Sea Is My Brother

The Sea Is My Brother The Town and the City: A Novel

The Town and the City: A Novel Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Desolation Angels: A Novel

Desolation Angels: A Novel Book of Sketches

Book of Sketches Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha

Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha The Electrocution of Block 38383939383

The Electrocution of Block 38383939383 Haunted Life

Haunted Life Visions of Gerard

Visions of Gerard Orpheus Emerged

Orpheus Emerged Book of Blues

Book of Blues The Subterraneans

The Subterraneans The Haunted Life

The Haunted Life The Unknown Kerouac

The Unknown Kerouac The Town and the City

The Town and the City Visions of Cody

Visions of Cody Atop an Underwood

Atop an Underwood Lonesome Traveler

Lonesome Traveler Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg Vanity of Duluoz

Vanity of Duluoz Desolation Angels

Desolation Angels On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition)

On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition) The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel

The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel Wake Up

Wake Up The Poetry of Jack Kerouac

The Poetry of Jack Kerouac Doctor Sax

Doctor Sax