- Home

- Jack Kerouac

Desolation Angels: A Novel Page 30

Desolation Angels: A Novel Read online

Page 30

“Great!”

On the floor of her bedroom as she starts the record player I just kiss her, down to the floor, like a foe—she responds foe-like by saying if she’s gonna make love it aint gonna be on the floor. And now, for the sake of a 100% literature, I’ll describe our loving.

28

It’s like a big surrealistic drawing by Picasso with this and that reaching for this and that—even Picasso doesnt want to be too accurate. It’s the Garden of Eden and anything goes. I cant think of anything more beautiful in my life (& aesthetic) than to hold a naked girl in my arms, sideways on a bed, in the first preliminary kiss. The velvet back. The hair, in which Obis, Parañas & Euphrates run. The nape of the neck the original person now turned into a serpentine Eve by the Fall of the Garden where you feel the actual animal soul personal muscles and there’s no sex—but O the rest so soft and unlikely—If men were as soft I’d love them as so—To think that a soft woman desires a hard hairy man! The thought of it amazes me: where’s the beauty? But Ruth explains to me (as I asked, for kicks) that because of her excessive softness and bellies of wheat she grew sick and tired of all that, and desired roughness—in which she saw beauty by contrast—and so like Picasso again, and like in a Jan Müller Garden, we mortified Mars with our exchanges of hard & soft—With a few extra tricks, politely in Vienna—that led to a breathless timeless night of sheer lovely delight, ending with sleep.

We ate each other and plowed each other hungrily.

The next day she told Erickson it was the first extase of her career and when Erickson told me that over coffee I was pleased but really didnt believe it. I went down to 14th Street and bought me a red zipper sweat jacket and that night Irwin and I and the kids had to go look for rooms. At one point I almost bought a double room in the Y.M.C.A. for me and Laz but I thought better of it realizing he’d be a weight on my few remaining dollars. We finally found a Puerto Rican roominghouse room, cold and dismal, for Laz, and left him there dismally. Irwin and Simon went to live with rich scholar Phillip Vaughan. That night Ruth Heaper said I could sleep with her, live with her, sleep with her in her bedroom every night, type all morning while she went to work in an agency and talk to Ruth Erickson all afternoon over coffee and beer, till she got back home at night, when I’d rub her new skin rash with unguents in the bathroom.

29

Ruth Erickson had a huge dog in the apartment, Jim, who was a giant German Police Dog (or Shepherd) (or Wolf) who loved to wrassle with me on the varnished wooden floor, by fireplaces—He’d have eaten whole assemblies of hoodlums and poets at one command but he knew Ruth Erickson liked me—Ruth Erickson called him her lover. Once in a while I took him out on a leash (for Ruth) to run him up and down curbstones for his peepees and works, he was so strong he could drag you half a block in search of a scent. Once when he saw another dog I had to dig my heels into the sidewalk to hold him. I told Ruth Erickson it was cruel to keep such a big monstrous man on a leash in a house but it turned out he’d just almost recently died and it was Erickson who saved his life with 24-hour care, she really loved him. In her own bedroom was a fireplace and jewelry on her dresser. At one point she had a French Canadian from Montreal go in there whom I didnt trust (he borrowed $5 from me and never paid it back) and did away with one of her expensive rings. She questioned me about who could have taken it. It wasnt Laz, it wasnt Simon, it wasnt Irwin, it wasnt me, for sure. “It’s that crook from Montreal.” She actually wanted me to be her lover in a way but loved Ruth Heaper so it was out of the question. We spent long afternoons talking and looking into each other’s eyes. When Ruth Heaper came from work we made spaghetti and had big meals by candlelight. Every evening another potential lover came for Erickson but she rejected all of them (dozens) except the French Canadian, who never made it (except possibly with Ruth Heaper when I was away) and Tim McCaffrey, who did make it he said with my blessings. He himself (a young Newsweek staffer with big James Dean hair) came and asked me if it was okay, apparently Erickson had sent him, to pull my leg.

Who could think of anything better? Or worse?

30

Why “worse”? Because by far the sweetest gift on earth, inseminating a woman, the feeling of that for a tortured man, leads to children who are torn out of the womb screaming for mercy as tho they were being thrown to the Crocodiles of Life—in the River of Lives—which is what birth is, O Ladies & Gentlemen of gentle Scotland—“Babies born screaming in this town are miserable examples of what happens everywhere,” I once wrote—“Little girls make shadows on the sidewalk shorter than the Shadow of death in this town,” I also wrote—Both the Ruths had been born screaming girls but at age 14 they suddenly got the urge sexily & snakily to make others cream & scream—It’s awful—The essential teaching of the Lord Buddha was: “No More Rebirth” but this teaching was taken over, hidden, controverted, turned upside down and defamed into Zen, the invention of Mara the Tempter, Mara the Insane, Mara the Devil—Today whole big intellectual books are being published about “Zen” which is nothing but the Devil’s Personal war against the essential teaching of Buddha who said to his 1250 boys when the Courtesan Amra and her girls were approaching with gifts across the Bengali Meadow: “Tho she is beautiful, and gifted, ’t were better for all of you to fall into a Tiger’s mouth than to fall into her net of plans.” Oyes? Meaning by that, for every Clark Gable or Gary Cooper born, with all the so called glory (or Hemingway) that goes with it, comes disease, decay, sorrow, lamentation, old age, death, decomposition—meaning, for every little sweet lump of baby born that women croon over, is one vast rotten meat burning slow worms in graves of this earth.

31

But nature has made women so maddeningly desirable for men, the unbelievable, the impossible-to-actually-believe wheel of birth and dying turns on and turns on, as tho some Devil was turning the Wheel himself hard and sweaty for suffering human horror to try to make an imprint somehow in the void of the sky—As tho anything, even a Pepsi Cola ad with jetplanes, could be printed up there, unless the Apocalypse—But Devilish nature has so worked it that men desire women and women scheme for men’s babies—Something we were proud of when we were Lairds but which today makes us sick to think of it, whole supermarket electronic doors opening by themselves to admit pregnant women so they can buy food to feed death further—Bluepencil me that, U.P.I.—

But a man is invested with all this trembling tissue, the Hindus call it “Lila” (Flower), and there’s nothing he can do with his tissue save get him to a monastery where however horrible male perverts sometimes wait for him anyway—So why not loll in the love of belly wheat? But I knew the end was coming.

Irwin was absolutely right about visiting the publishers and arranging for publication and money—They advanced me $1000 payable at $100 a month installments and the editors (without my knowledge) bent their wrenny heads over my faultless prose and prepared the book for publication with a million faux pas of human ogreishness (Oy?)—So I actually felt like marrying Ruth Heaper and moving to a country home in Connecticut.

Her skin rash, according to soulmate Erickson, was caused by my arrival and lovemaking.

32

Ruth Erickson and I had daylong talks during which she confided her love for Julien in me—(what?)—Julien my best friend, perhaps, with whom I’d been living in a loft on 23rd Street when first met Ruth Erickson—He was madly in love with her at the time but she did not reciprocate (as I knew she’d do, at the time)—But now that he was married to that most charming of earth’s women, Vanessa von Salzburg, my witty buddy and confidante, O now she wanted Julien! He’d even telephoned her long distance in the Middle West but to no avail at the time—Missouri River in her hair indeed, Styx, or Mytilene more likely.

There’s old Julien now, home from work at the office where he’s a successful young executive in a necktie with a mustache tho in his early days he’d sat in puddles of rain with me pouring ink over our hair yelling Mexican Borracho Yahoos (or Missourian, one)—The moment he come

s home from work he plumps into the splendid leather easy chair his Laird’s wife’s bought him first thing off, before cribs, and sits there before a crackling fire tweaking his mustache—“Nothing to do but raise kids and tweak your mustache,” said Julien who told me he was the new Buddha interested in rebirth!—The new Buddha dedicated to Suffering!—

I’d often visited him in the office and watched him work, his office style (“Hey you fucker come ’ere!”) and his speech clack (“Whatsamatter with you, any lil old West Virginia suicide is worth ten tons of coal or John L. Lewis!”)—He saw to it that the most (to him) important and saddy-dolly stories got over the A.P. wire—He was the favorite of the very frigging President of the whole wire service, Two-Fisted So-and-So Joe—His apartment where I hung out in the afternoons except those afternoons when I kaffee-klatched with Erickson was the most beautiful apartment in Manhattan in its own Julien-like way, with small balcony overlooking all the neons and trees and traffics of Sheridan Square, and a kitchen refrigerator full of ice cubes and Cokes to go with ye old Partners Choice Whiskeyboo—I’d spend the day talking to Wife Nessa and the kids, who told us to shush when Mickey Mouse came on TV, then in’d walk Julien in his suit, open collar, tie, saying “Shit—imagine comin home from a hard day’s work and finding this McCarthyite Duluoz here” and sometimes he’d be followed by one of his assistant editors like Joe Scribner or Tim Fawcett—Tim Fawcett who was deaf, had a hearing aid, was a suffering Catholic, and still loved suffering Julien—Plup, Julien falls in his leather easy chair before a Nessa-prepared fire, and tweaks his mustache—It was the theory of Irwin and Hubbard too that Julien grew that mustache to look older and uglier than he wasnt at all—“Anything to eat?” he says, and Nessa comes out with half a broiled chicken at which he picks desultorily, has a coffee, and wonders if I’ll go down and get another pint of Partners Choice—

“I’ll pay half.”

“Ah you Kanooks are always payin half” so we go down together with Potchki the black spaniel on the leash, and before the liquor store we hit a bar and have a few rye and Cokes watching TV with all the other sadder New Yorkers.

“Bad blood, Duluoz, bad blood.”

“Whattaya mean?”

He suddenly grabs me by the shirt and pulls it yanking two buttons off.

“Why are you always tearing my shirt?”

“Ah your mother aint here to sew em, hey?” and he pulls further, tearing my poor shirt, and looks at me sadly, Julien’s sad look is a look that says:—

“Ah shit man, all your and my little tight ass schemes to make 24 hours a day run discipline the clock—when we all go to heaven we wont even know what the sighin was all about or what we looked like.” Once I’d met a girl and told him: “A girl that’s beautiful, sad” and he’d said “Ah everybody’s beautiful and sad.”

“Why?”

“You wouldnt know, you bad blooded Kanook—”

“Why do you keep sayin I’ve bad blood?”

“Cause you grow tails in your family.”

He’s the only man in the world who can insult my family, really, because he’s insulting the family of earth.

“What about your family?”

He doesnt even hear to answer:—“If you had a crown on your head they’d have to hang you even sooner.” Back upstairs at the apartment he starts exciting the female dog by stimulating her: “Oh what a black dribbling bottom …”

There’s a December blizzard going on. Ruth Erickson comes over, as arranged, and she and Nessa talk and talk while me and Julien sneak out to his bedroom and go down the fire escape in the snow to hit the bar for some more rye and soda. I see him jump nimbly beneath me so I do the same nimble jump. But he’s done it before. It’s a ten-foot drop from that swinging fire escape to the sidewalk and as I fall I realize it but not soon enough, and turn over in my fall and fall right on my head. Crack! Julien lifts me up with a bleeding head. “All that for just running out on the women? Duluoz you look better when you’re bleeding.”

“All that bad blood going out,” he adds in the bar, but there’s nothing cruel about Julien, just just. “They used to bleed nuts like you in old England” and when he begins to see the pained expression on my face he becomes commiserative.

“Ah poor Jack” (head against mine, like Irwin, for the same and yet not the same reasons), “you should have stayed wherever you were before you came here—” He calls the bartender for mercurochrome to fix my wound. “Old Jack,” there are times too when he becomes absolutely humble in my presence and wants to know what I really think, or he really thinks. “Your opinions are now valuable.” The first time I’d met him in 1944 I thought he was a mischievous young shit, and the only time I got high on pot in his presence I divined he was against me, but since we were always drunk … and yet. Julien with his slitted green eyes and Tyrone Power slender wiry masculinity punching me. “Let’s go see your girl.” We take a cab to Ruth Heaper’s in the snow and as soon as we walk in and she sees me drunk she grabs a handful of my hair, pulls it, pulls several hairs out of my important combing spot and starts punching fists into my face. Julien sits there calling her “Slugger.” So we leave again.

“Slugger dont like you, man,” Julien says cheerfully in the cab. We go back to his wife and Erickson who are still talking. Gad, the greatest writer who ever lived will have to be a woman.

33

Then it’s time for the late show on tv so me and Nessa make more ryes and Cokes in the kitchen, bring them out tinkly by the fire, and we all draw our chairs before the TV screen to watch Clark Gable and Jean Harlow in a picture about rubber plantations in the 1930’s, the parrot cage, Jean Harlow is cleaning it out, says to the Parrot: “What you ben eatin, cement?” and we all roar with laughter.

“Boy they dont make pictures like that anymore” says Julien sipping his drink, tweaking his mustache.

On comes a Late Late film about Scotland Yard. Julien and I are very quiet watching our old histories while Nessa laughs. All she had to deal with in her previous lifetime were baby carriages and daguerrotypes. We watch the Lloyds of London Werewolf crap out the door with a slanting leer:—

“That sonofabitch wouldnt a given you two cents for your own mother!” yells Julien.

“Even with a bedstead,” adds I.

“’Avin ’is ’anging in Turkish Baths!” yells Julien.

“Or in Innisfree.”

“Throw another log on the fire, Muzz,” says Julien, “Dazz” to the kids, to Muzz Momma, which she does with great pleasure. Our movie reveries are interrupted by visitors from his office: Tim Fawcett yelling because he’s deaf:—

“C a—rist! That U.P.I. dispatch told all about some mother who was a whore who had to do with all the little bastard’s horror!”

“Well the little bastard’s dead.”

“Dead? He blew his head clean off in a hotel room in Harrisburg!”

Then we all get drunk and I end up sleeping in Julien’s bedroom while he and Nessa sleep on the open-out couch, I open the window to the fresh air of the blizzard and fall asleep beneath the old oil portrait of Julien’s grandfather Gareth Love who is buried next to Stonewall Jackson in Lexington Virginia—In the morning I wake up to two feet of snowdrifts over the floor and part of the bed. Julien is sitting in the livingroom pale and sick. He wont even touch a beer, he has to go to work. He has one softboiled egg and that’s it. He puts on his necktie and shudders with horror to the office. I go downstairs, buy more beer, and spend the whole day with Nessa and the kids talking and playing their piggy back games—Come dark in comes Julien again, two hiballs stronger, and falls to drinking again. Nessa brings our asparagus, chops and wine. That night the whole gang (Irwin, Simon, Laz, Erickson and some writers from the Village some of them Italian) come in to watch TV with us. We see Perry Como and Guy Lombardo hugging each other on a Spectacular. “Shit,” says Julien, drink in hand in the leather chair, not even tweaking his mustache, “them Dagos’ll all go home and eat ravioli and die of pukin

g.”

I’m the only one who laughs (except Nessa secretly) because Julien is the only guy in New York who’ll speak his mind whatever his mind is at the time it happens, no matter what, which is why I love him:—a Laird, sirs (Dagos excuse us).

34

I had once seen a photo of Julien when he was 14, in his mother’s house, and was amazed that any person could be so beautiful—Blond, with an actual halo of light around his hair, strong hard features, those Oriental eyes—I’d thought “Shit would I have liked Julien when he was 14 looking like that?” but no sooner I tell his sister what a great picture it was she hid it, so the next time (a year later) when we again accidentally visit her apartment on Park Avenue “Where’s that great picture of Julien?” it’s gone, she’s hid it or destroyed it—Poor Julien, over whose blond head I see the stare of America’s Parking Lots and Bleakest Glare—the Glare of “Who-are-you, Ass?”—A sad little boy finally, whom I understood, because I’d known many sad little boys in Oy French Canada as I’m sure Irwin had known in Oy New York Jews—The little boy too beautiful for the world but finally saved by a wife, good old Nessa, who said to me one time: “While you were passed out on the couch I noticed your pants were shining!”

Once I’d said to Julien “Nessa, I’m gonna call her ‘Legs’ because she has nice legs” and he answered:—

“If I catch you making any pass at Nessa I’ll kill you” and he meant it.

His sons were Peter, Gareth and one was on the way who would be known as Ezra.

35

Julien was mad at me because I’d made love to one of his old girlfriends, not Ruth Erickson—But meanwhile while we were having a party at the Ruths some rotten eggs were thrown up at Erickson’s window and I went downstairs with Simon later to investigate. Only a week before Simon and Irwin had been stopped by a gang of juvenile delinquents with broken bottles at their throats, only because Simon had looked at the gang in front of the variety (variety indeed) store—Now I saw the kids and said “Who threw those rotten eggs?”

Tristessa

Tristessa On the Road

On the Road The Dharma Bums

The Dharma Bums Maggie Cassidy

Maggie Cassidy Big Sur

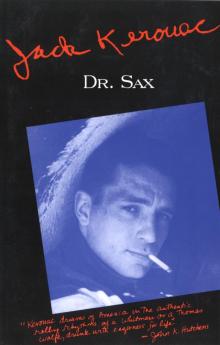

Big Sur Dr. Sax

Dr. Sax Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46

Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46 The Sea Is My Brother

The Sea Is My Brother The Town and the City: A Novel

The Town and the City: A Novel Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Desolation Angels: A Novel

Desolation Angels: A Novel Book of Sketches

Book of Sketches Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha

Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha The Electrocution of Block 38383939383

The Electrocution of Block 38383939383 Haunted Life

Haunted Life Visions of Gerard

Visions of Gerard Orpheus Emerged

Orpheus Emerged Book of Blues

Book of Blues The Subterraneans

The Subterraneans The Haunted Life

The Haunted Life The Unknown Kerouac

The Unknown Kerouac The Town and the City

The Town and the City Visions of Cody

Visions of Cody Atop an Underwood

Atop an Underwood Lonesome Traveler

Lonesome Traveler Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg Vanity of Duluoz

Vanity of Duluoz Desolation Angels

Desolation Angels On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition)

On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition) The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel

The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel Wake Up

Wake Up The Poetry of Jack Kerouac

The Poetry of Jack Kerouac Doctor Sax

Doctor Sax