- Home

- Jack Kerouac

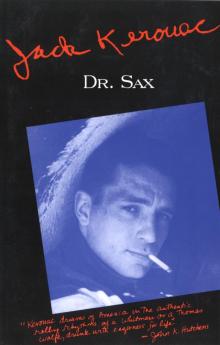

Doctor Sax Page 4

Doctor Sax Read online

Page 4

“Jey-sas Crise what a maniac!”

“Is he crazy— you know what he did? He stuck his finger up his ass and said Woo Woo—”

“He came fifteen comes, no kiddin, he jumped around jacking himself off all that whole day–the 920 club was on the radio, Charlie was at work–Zaza the madman.”

This tenement was located across the street from the Pawtucketville Social Club, an organization intended to be some kind of meeting place for speeches about Franco-American matters but was just a huge roaring saloon and bowling alley and pool table with a meetingroom always locked. My father that year was running the bowling alley, great cardgames of the night we imitated all day in Vinny’s house with whist for Wing cigarettes. (I was the only one who didn’t smoke, Vinny used to smoke two cigarettes at a time and inhale deep as he could.) We didn’t give a shit about no Doctor Sax.

Great big bullshitters, friends of Lucky’s, grown men, would come in and regale us with fantastic lies and stories —we screamed at them “What a bullshitter, geez, I never– is he a bullshitter!” Everything we said was put this way, “Oh is my old man gonna kick the shit out of me if he ever finds out about those helmets we stole, G.J.”

“Ah fuckit, Zagg–helmets is helmets, my old man’s in the grave and no one’s the worse for it.” At 11 or 12 G.J. was so Greekly tragic he could talk like that–words of woe and wisdom poured from his childly dewy glooms. He was the opposite of crackbrained angel joy Vinny. Scotty just watched or bit his inner lip in far away silence (thinking about that game he pitched, or Sunday he’s got to go to Nashua with his mother to see Uncle Julien and Aunt Yvonne (Mon Mononcle Julien, Ma Matante Yvonne)— Lousy is spitting, silently, whitely, neatly, just a little dew froth of symbolic spit, clean enough to wash your eyeballs in–which I had to do when he got sore and his aim was champion in the gang.—Spitting out the window, and turns to giggle with a laugh in the joke general, slapping his knees softly, rushing over to me or G.J. half kneeling on the floor to whisper a confidential observation of glee, sometimes G.J. would respond by grabbing him by the hair and dragging him around the room, “Ooh this fuckin Lousy has just told me the dirtiest–is he–Ooh is he got dirty thoughts— Ooh, would I love to kick his ass–allow me, gentlemen, stand back, to kick the ass of Lauzon Cave-In in his means, lookout Slave don’t desist! or try to run! frup, gluck, aye, haye!” he’s screaming as Lousy suddenly squeezes his balls to break the hair hold. Lousy is the sneakiest most impossible to wrastle snake—(Snake!)—in the world–

When we turned the subject to gloom and evil (dark and dirty and dying), we talked of the death of Zap Plouffe, Gene’s and Joe’s kid brother our age (with those backstore stories maybe told by malicious mothers who hated the Plouffes and especially the dying melancholy old man in his dark house). Zap’s foot was dragged under a milk wagon, he caught infection and died, I first met Zap on a crazy screaming night about the third after we’d moved from Centralville to Pawtucketville (1932) on my porch (Phebe), he came rollerskating up on the porch with his long teeth and prognathic jaw of the Plouffes, he was the first Pawtucketville boy to talk to me… And the screams in the nightfall street of play!–

“Mon nom cest Zap Plouffe mué—je rests au coin dans maison la”—(my name it is Zap Plouffe me–I live on the corner in the house there).

Not long after, G.J. moved in across the street, with dolorous furnitures from the Greek slums of Market Street where you hear the wails of Oriental Greek records on Sunday afternoon and smell the honey and the almond. “Zap’s ghost is in that goddam park,” G.J. said, and never walked home across the field, instead went Riverside-Sarah or Gershom-Sarah, Phebe (where he lived all those years) was the center of those two prongs.

The Park is in the middle, Moody’s across the bottom.

So I began to see the ghost of Zap Plouffe mixed with other shrouds when I walked home from Destouches’ brown store with my Shadow in my arm. I wanted to face my duty–I had learned to stop crying in Centralville and I was determined not to start crying in Pawtucketville (in Centralville it was Ste. Therese and her turning plaster head, the crouching Jesus, visions of French or Catholic or Family Ghosts that swarmed in corners and open closet doors in mid sleep night, and the funerals all around, the wreaths on old wood white door with paint cracking, you know some old gray ash-faced dead ghost is waxing his profile to candlelight and suffocating flowers in the broon-gloom of dead relatives kneeling in a chant and the son of the house is wearing a black suit Ah Me! and the tears of mothers and sisters and frightened humans of the grave, the tears flowing in the kitchen and by the sewing machine upstairs, and when one dies–three will die) … (two more will die, who will it be, what phantom is pursuing you?). Doctor Sax had knowledge of death … but he was a mad fool of power, a Faustian man, no true Faustian’s afraid of the dark–only Fellaheen–and Gothic Stone Cathedral Catholic of Bats and Bach Organs in the Blue Mid Night Mists of Skull, Blood, Dust, Iron, Rain burrowing into earth to snake antique.

As the rain hit the windowpane, and apples swelled on the limb, I lay in my white sheets reading with cat and candy bar … that’s where all these things were born.

20

THE UNDERGROUND RUMBLING HORROR OF THE LOWELL NIGHT —a black coat on a hook on a white door–in the dark— -o-o-h!—my heart used to sink at sight of huge headshroud rearing on his rein in the goop of my door– Open closet doors, everything under the sun’s inside and under the moon–brown handles fall out majestically–supernumerary ghosts on different hooks in a bad void, peeking at my sleep bed–the cross in my mother’s room, a salesman had sold it to her in Centralville, it was a phosphorescent Christ on a black-lacquered Cross–it glowed the Jesus in the Dark, I gulped for fear every time I passed it the moment the sun went down, it took that own luminosity like a bier, it was like Murder by the Clock the horrible fear-shrieking movie about the old lady clacking out of her mausoleum at midnight with a–you never saw her, just the woeful shadow coming up the davenport tap-tap-tap as her daughters and sisters screech all over the house– Never liked to see my bedroom door even ajar, in the dark it yawned a black dangerhole.—Square, tall, thin, severe, Count Condu has stood in my doorway many’s the time– I had an old Victrola in my bedroom which was also ghostly, it was haunted by the old songs and old records of sad American antiquity in its old mahogany craw (that I used to reach in and punch for nails and cracks, in among the needle dusts, the old laments, Rudies, magnolias and Jeannines of twenties time)— Fear of gigantic spiders big as your hand and hands as big as barrels–why … underground rumbling horrors of the Lowell night–many.

Nothing worse than a hanging coat in the dark, extended arms dripping folds of cloth, leer of dark face, to be tall, statuesque, motionless, slouch headed or hatted, silent– My early Doctor Sax was completely silent like that, the one I saw standing–on the sandbank at night–an earlier time we were playing war in the sandbank at night (after seeing The Big Parade with Slim Summerville in muddy)— we played crawling in the sand like World War I infantrymen on the front, putteed, darkmouthed, sad, dirty, spitting on clots of mud– We had our stick rifles, I had a broken leg and crawled most miserably behind a rock in the sand … an Arabian rock, Foreign Legion now … there was a little sand road running through the sand field valley–by starlight bits of silver sand would sparkle-the sandbanks then rose and surveyed and dipped for a block each way, the Phebe way ending at houses of the street (where lived the family of the white house with flowers and marble gardens of whitewash all around, daughters, ransoms, their yard ended at the first sandbank which was the one I was pelting with pitching rocks the day I met Dicky Hampshire —and the other way ending on Riverside in a steep cliff) (my intelligent Richard Hampshire)— I saw Doctor Sax the night of the Big Parade in the sand, somebody was convoying a squad to the right flank and being forced to take cover, I was reconnoitering with views at the scenery for possible suspects and trees, and there’s Doctor Sax grooking in the desert plateau of timbers in brush, t

he all-stars of Whole World strung up behind him à la bowl, meadows and apple trees as a background horizon, clear pure night, Doctor Sax is watching our pathetic sand game with an inscrutable silence– I look once, I look, he vanisheth on falling horizons in a bat… what great difference was there between Count Condu and Doctor Sax in my childhood?

Dicky Hampshire introduced me to a possible difference … we started drawing cartoons together, in my house at my desk, in his house in his bedroom with kid brother watching (just like Paddy Sorenson’s kid brother watching me and Paddy drawing 4-year-old cartoons–abstract as hell–as the Irish washingmachine wrangles and the old Irish grandfather puffs on his clay upsidedown pipe, on Beaulieu Street, my first “English” chum)— Dicky Hampshire was my greatest English chum, and he was English. Strangely, his father had an old Chandler car in the yard, year ‘29 or ‘21, probably ‘21, wood spokes, like some wrecks you find in the Dracut woods smelling of shit and all sagged down and full of rotten apples and dead and all ready to sprout out of the earth a new car plant, some kind of Terminus pine plant with sagging oil gums and rubber teeth and an iron source in the center, a Steel tree, an old car like that is often seen but rarely intact, although it wasn’t running. Dicky’s father worked in a printing plant on a canal, just like my father … the old Citizen newspaper that went out —blue with mill rags in the alleys, cotton dust balls and smoke pots, litter, I walk along the long sunny concrete rale of the millyards in the booming roar of the windows where my mother’s working, I am horrified by the cotton dresses of the women rushing out of the mills at five–the women work too much! they’re not home any more! They work more than they ever worked!— Dicky and I covered these millyards and agreed millwork was horrible. “What I’m going to do instead is sit around the green jungles of Guatemala.”

“Watermelon?”

“No, no, Guatemala–my brother s going there—”

We drew cartoons of jungle adventures in Guatemala. Dicky’s cartoons were very good–he drew slower than I did– We invented games. My mother made caramel pudding for both of us. He lived up Phebe across the sandbank. I was the Black Thief, I put notes in his door.

“Beware, Tonight the Black Thief will Strike Again. Signed, the Black Thief!!!”-and off I’d flit (in broad daylight planting notes). At night I came in my cape and slouch hat, cape made of rubber (my sister’s beach cape of the thirties, red and black like Mephistopheles), hat is old slouch hat I have … (later I wore great big felt hats all level to imitate Alan Ladd This Gun for Hire, at 19, so what’s silly)— I glided to Dicky’s house, stole his bathing trunks from the porch, left a note on the rail under a rock, “The Black Thief Has Struck.”- Then I’d run-then I’d in the daytime stand with Dicky and the others.

“I wonder who that Black Thief is?”

“I think he lives on Gershom, that’s what I think.”

“It might be,—it might be,—then again–I dunno.”

I’m standing there speculating. For some odd reason having to do with his personal psychological position (psyche) Dicky became terrified of the Black Thief–he began to believe in the sinister and heinous aspects of the deal —of the–secretive—perfectly silent–action. So sometimes I’d see him and break his will with stories— “On Gershom he’s stealing radios, crystal sets, stuff in barns—”

“What’ll he steal from me next? I lost my hoop, my pole vault, my trunks, and now my brother’s wagon … my wagon.”

All these articles were hidden in my cellar, I was going to return them quite as mysteriously as they disappeared —at least so I told myself. My cellar was particularly evil. One afternoon Joe Fortier had cut off the head of a fish in it, with an ax, just because we caught the fish and couldn’t eat it as it was an old dirty sucker from the river (Merrimac of Mills)—boom–crash—I saw stars–I hid the loot there, and had a secret dusty airforce made of cross-beam sticks with crude nail landing gears and a tail all hid in the old coal bin, ready for pubertical war (in case I got tired of the Black Thief) and so–I had a light dimly shining down (a flashlight through a cloth of black and blue, thunder) and this shone dumb and ominous on me in my cape and hat as outside the concrete cellar windows redness of dusk turned purple in New England and the kids screamed, dogs screamed, streets screamed, as elders dreamed, and in the back fences and violet lots I skipped in a flowing cape guile through a thousand shadows each more potent than the other till I got (skirting Dicky’s house to give him a rest) to the Ladeaus’ under the sandbank streetlamp where 1 threw surreptitious pebbles among their skippity hops in the dirt road (on cold November sunnydays the sand dust blew on Phebe like a storm, a drowsy storm of Arabic winter in the North)—the Ladeaus searched the hills of sand for this Shadow-this thief-this Sax incarnate pebblethrower —didn’t find him–I let go my “Mwee hee hee ha ha” in the dark of purple violet bushes, I screamed out of earshot in a dirt mole, went to my Wizard of Oz shack (in Phebe backyard, it had been an old ham-curing or tool-storing shack) and drop’t in through the square hole in the roof, and stood, relaxed, thin, huge, amazing, meditating the mysteries of my night and the triumphs of my night, the glee and huge fury of my night, mwee hee hee ha ha— (looking in a little mirror, flashing eyes, darkness sends its own light in a shroud)— Doctor Sax blessed me from the roof, where he hid–a fellow worker in the void! the black mysteries of the World! Etc! the World Winds of the Universe!—I hid in this dark shack–listening outside–a madness in the bottom of my darkness smile–and gulped with fear. They finally caught me.

Mrs. Hampshire, Dick’s mother, said to me gravely in the eye, “Jack, are you the Black Thief?”

“Yes, Mrs. Hampshire,” I replied immediately, hypnotized by the same mystery that once made her say, when I asked her if Dicky was at home or at the show, in a dull, flat, tranced voice as if she was speaking to a Spiritualist, “Dicky … is … gone … far … away …”

“Then bring back Dicky’s things and tell him you’re sorry.” Which I did, and Dicky was wiping his red wet eyes with a handkerchief.

“What foolish power had I discovered and been possessed by?” I asts meself … and not much later my mother and sister came impatiently marching down the street to fetch me from the Ladeau bushes because they were looking for the beach cape, a beach party was up. My mother said exasperated:

‘I’m going to stop you from reading them damned Thrilling Magazines if it’s the last thing I do (Tu va arretez d’lire ca ste mautadite affaire de fou la, tu m’attend tu?)”—

The Black Thief note I printed, by hand, in ink, thickly, on beautiful scraps of glazed paper I got from my father’s printing shop– The paper was sinister, rich, might have scared Dicky–

21

“I AM TOO FEEBLE TO GO ON,” says the Wizard in the Castle bending over his papers at night.

“Faustus!” cries his wife from the bath, “what are you doing up so late! Stop fiddling with your desk papers and pen quills in the middle of the night, come to bed, the mist is on the air of night lamps, a dewll come to rest your fevered brow at morning,—you’ll lie swaddled in sweet sleep like a lambikin—l’ll hold you in my old snow-white arms–and all you do’s sit there dreaming—”

“Of Snakes! of Snakes!” answers the Master of Earthly Evil–sneering at his own wife: he has a beak nose and movable jaw-bird beak and front teeth missing and something indefinably young in bone structure but imponderably old in the eyes–horrible old bitch face of a martinet with books, cardinals and gnomes at his spidery behest.

“Would I’d never seen your old fink face and married you–to sit around in bleak castles all my life, for varmints in the dirt!”

“Flap up you old sot and drink your stinking brandignac and conyoles, fit me an idea for chat, drive me not mad with your fawter toddle in a gloom . . . you with your pendant flesh combs and bawd spots–picking your powderies in a nair–flam off, frish frowse, I want peace to Scholarize my Snakes–let me Baroque be.”

By this time the old lady’s asleep�

� Wizard Faustus hurries in his wrinkly feet to a meet with Count Condu and the Cardinals in the Cave Room … his footsteps clang along an iron underhall–There stands a gnome with a pass key, a little glucky monster with web feet or some such —heavy rags wrapped around each foot and around the head almost blinding the eyes, a weird crew, their leader sported a Moro saber and had a thin little neck you’d expect from a shrunk head… The Wizard comes to the Parapet to contemplate.

He looks down into the Pit of Night.

He hears the Snake Sigh and Inch.

He moves his hand three times and backs, he waves a bow with his wrists, and walks down the long sand hill of a grisly part of the Castle with shit in the sand and old boards and moisture down the mossy ratty granite walls of an old dongeon–where gnome children masturbated and wrote obscenities with whitewash brushes like advertisements of Presidents in Mexico.

Tristessa

Tristessa On the Road

On the Road The Dharma Bums

The Dharma Bums Maggie Cassidy

Maggie Cassidy Big Sur

Big Sur Dr. Sax

Dr. Sax Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46

Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46 The Sea Is My Brother

The Sea Is My Brother The Town and the City: A Novel

The Town and the City: A Novel Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Desolation Angels: A Novel

Desolation Angels: A Novel Book of Sketches

Book of Sketches Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha

Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha The Electrocution of Block 38383939383

The Electrocution of Block 38383939383 Haunted Life

Haunted Life Visions of Gerard

Visions of Gerard Orpheus Emerged

Orpheus Emerged Book of Blues

Book of Blues The Subterraneans

The Subterraneans The Haunted Life

The Haunted Life The Unknown Kerouac

The Unknown Kerouac The Town and the City

The Town and the City Visions of Cody

Visions of Cody Atop an Underwood

Atop an Underwood Lonesome Traveler

Lonesome Traveler Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg Vanity of Duluoz

Vanity of Duluoz Desolation Angels

Desolation Angels On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition)

On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition) The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel

The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel Wake Up

Wake Up The Poetry of Jack Kerouac

The Poetry of Jack Kerouac Doctor Sax

Doctor Sax