- Home

- Jack Kerouac

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg Page 5

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg Read online

Page 5

Anyway, if we traced the currents of poetry, I think that in the end the whole art making machine (in yourself as in myself) would be egocentric, whether we wish to deceive ourselves with other ideas. And in the end, and with Julian [Lucien Carr]. He does not wish to dedicate himself to another, except as far as for him it will dedicate another to him. Love is only a recognition of our own guilt and imperfection, and a supplication for forgiveness to the perfect beloved. This is why we love those who are more beautiful than ourselves, why we fear them, and why we must be unhappy lovers. When we make ourselves high priests of art we deceive ourselves again, art is like a genie. It is more powerful than ourselves, but only by virtue of ourselves does it exist and create. Like a genie it has no will of its own, and is, even somewhat stupid; but by our will it moves to build our gleaming palaces and provide a mistress for the palace, which is most important. The high priest is a cultist, who worships the genie that someone else has invoked.

You say you are keeping Trilling’s letter, my true friend, and that I shall realize the quality of your friendship by advertising it for me. My self-souled aggrandizing lust seems to have convinced you of the validity of my clay pigeon complex. Well, you are the ungrateful one—and I had the temerity to tell Trilling (half year ago) that you were a genius. This is the thanks I get! (Incidentally, I think that half the reason I told him that was to get him to think that my friends were geniuses and by implication, etc. Still, I risked my reputation on you.)

Aside from all of this frivolity I was surprised by your belief that whenever you show your affectionate nature to me I become condescending—I think that it has been oppositely so. Do you really find it like that?

Incidentally—I was ashamed to tell you before Burroughs—I wrote Trilling an 8 page letter explaining (my version) the Rimbaud Weltschaung. It was mostly an exegesis of Bill’s Spenglerian and anthropological ideas. I feel sort of foolish now—over bumptious.

I think I’ll be in N.Y.—at Bill’s—Saturday night, maybe Sunday. I expect to have Monday off. I have no money, so I’ll have to seek introspective entertainment—C.

Is Gilmore really writing a novel?

Here are two sonnets on the poet which contain half of my versions of art.14

Allen

P.S. Don’t write unless there is something special. I don’t want to take your time and I will see you soon enough. Somehow I’d like to save your letters for tragic occasions, long farewells, or for voyages.

1948

Editors’ Note: Between September 1945 and April 1948 the letters were few and far between. During these years Jack and Allen spent a good deal of their time together, which made writing unnecessary. When their correspondence picks up again here, in 1948, they have both spent time at sea, met Neal Cassady, and made their first cross-country trips to the West to visit him, and their friendship has had its ups and downs.

Jack Kerouac [n.p., Ozone Park, New York?] to

Allen Ginsberg [n.p.]

ca. April 1948

Saturday night

Dear Allen

Distractions, excitement, and evil influences prevented me from absorbing what you were saying about Van Doren and the proposed publication of your doldrums.15 Thus, sit down and write me a letter about it. I’d go to see you about it only I’m so near to the end of my book that I tremble at the thought of leaving it for one moment. Exaggeration—but I can see you next weekend. Meanwhile I’d like to hear about it, more about it, circles of it briefly.

Meditating on the yiddishe kopfe heads I wonder if you were right about my taking Town and City to Van Doren instead of a publisher. Tell me what you think about that in your considered well-groomed Hungarian Brierly-in-thebathrobe 16 opinion. It seems to me perhaps that if I took my novel to publishers they would glance at it with jaundiced eyes knowing that I am unpublished and unknown, while if Van Doren approved of it, everything would be quite different. I imagine that’s what you think, too. We creative geniuses must bite fingernails together, or at least, we should, or perhaps, something or other.

Have you heard from Neal [Cassady]? Reason I ask, if I go to Denver on June 1st to work on farms out there I’d like to see him. It’s strange that he doesn’t right (write)—and as I say, he must be doing ninety days for something, only I hope it’s not ninety months, that’s what I’ve been really worrying about.

Hal [Chase] has been reading my novel and he said it was better than he thought it would be, which everybody says. As a matter of fact I don’t know much about it myself since I never read it consecutively, if at all. Hal is still amazingly Hal—you know, Hal at his best and most mysteriously intense self. What a strange guy. With a million unsuspected naiveté’s jumping over the monotone of his profundity. And it is a real profundity.

It’s funny that whenever I write to you nothing seems to sound right due to the fact that I keep imagining you saying, “But why? why is he saying that? what is the meaning of all this? what is it for?” Do you know, that sounds like Martin Spencer Lyons, big philosopher. Says, “What are you doing?” and you say: “Writing a novel” and [he] says: “WHY?”—with the voice of Gabriel, supposed to lay you flat under the why-and-wherefore of the universe. I tell you, man, a guy like Martin Spencer Lyons has been into the house of doubt-and-why and had to sneak out the back way, whereas you take me—I’ve been in that house and I wandered around all the rooms and I came out the way I came in. Ask me about the whys and wherefores of doing anything, or about the insanity of unconsciously contrived action, and I will say to you in my cardiest Mark Twain tone, “Shit, I even know the wall-termites in the house of why-and-wherefore by their first names.” Good, hey? All of which is supposed to mean that one shouldn’t ask why all the time, and therefore don’t ask why I’m writing you this letter. Actually it’s because I have a sudden urge to talk to you about it and also, subliminally, to complete a little circle we began last Saturday night when I borrowed a buck from you and we both smiled graciously like two old Jews in the garment business who know each other so well that they can smile falsely. Also, the buck is not forthcoming perhaps until I might see you this weekend.

So when you see Van Doren—tell him I plan to take my novel (380,000 words) to him, tell him I will take it to him in the middle or end of May, completed novel: tell him it’s the same one I told him about 2½ years ago and go and tell him that I have laboured through poverty, disease and bereavement and madness, and this novel hangs together no less. If that isn’t the pertinacity or the tenacity or something of genius I don’t know what is. Go tell him that I have been consumed by mysterious sorrowful time yet I have straddled times, that I have been saddest and most imperially time-haunted yet I have worked. And tell Martin Spencer Lyons, poor rueful ramshackle oddity that he is, that he has succeeded in annoying a man of action. So long man. Tell me of Hunkey [Huncke].

Man of enigma-knowledge and despair of aggression,

J.

P.S. The thing I like about Van Doren is this: he was the only professor I personally knew at Columbia who had the semblance of humility without pretensions—the semblance, but to me, deeply, the reality of humility too. A kind of sufferingly earnest humility like you imagine old Dickens or old Dostoevsky having later in their lives. Also he’s a poet, a “dreamer” and a moral man. The moral man part of it is my favorite part. This is the kind of man whose approach to life has the element in it of a moral proposition. Either the proposition was made to him or he made it himself, to life. See? My kind of favorite man. I have never been able to show these things to anyone from a fear of seeming hypocritical rather than sympathetic, or simpatico. Thus, if he should happen to like my novel, I would get the same feeling that Wolfe must have gotten from old [Maxwell] Perkins at Scribner’s—a filial feeling. It’s terrible never to find a father in a world chock-full of fathers of all sorts. Finally you find yourself as father, but then you never find a son to father. It must be awfully true, old man, that human beings make it hard for themselves, etc.

> P.S. Dig this line from my novel, in a Greenwich Village sequence: “In all these scenes (Greenwich Village parties) the grave Francis was like some veritable young officer of the church who had been defrocked early in his career after a scandal of tremendous theological proportions.”

P.S. And dig this description of New York: “They saw Manhattan itself towering across the river in the great red light of the world’s afternoon. It was too much to believe, near, almost near enough to touch (like the stars), and so huge, intricate, unfathomable and beautiful in its distance, smoking, window-flashing, canyon-shadowed realness there, with the weave of things touching and trembling at its watery apron below, and the pink light glowing on its highest towers as bottomless shadows hung draped in mighty abysms, and little things moving in millions as the eye strained to see, and the myriads of smoke rising and puffing everywhere, everywhere from down the shining raveled watersides right up the great flanks of city to the uppermost places, etc. etc.” Then it gets darker—“And it was so: the sun was setting, leaving a huge swollen light in the world that was like dark wine and rubies, and long sash-clouds the hues of velvet purple and bright rose above, all of it somber, dark, immense, and unspeakably beauteous all over: everything was changing, the river changing in a teeming of low colors to darkness (dig that?), the abysses of the streets to darkness, etc., fabulous thousand-starred glitter, etc., etc., and finally,—” as you look across the river to Brooklyn—“the swoop of the bridges across the river—the river like pennies—to Brooklyn, to the teeming, ship-complicated, weaving-soft incomprehensibly ruffled water’s-end and very ledge of Brooklyn.”

P.S. More, much more, but I’m tired

So long

Jack Kerouac [n.p., Ozone Park, New York?] to

Allen Ginsberg [n.p., New York, New York?]

Theme: All the young angels rolling to the music of celestial honkytonks. (in a

roller skating rink)

Tuesday night May 18 ’48

Dear Allen:

Thanks for writing. I’ll be seeing you perhaps this Friday night, but now I don’t want to discuss your letter17 in detail due to the fact that it’s a lot of ancient material with me. In answer to all your questions: yes. I have the same problems, of “personal-ness” in expression striving at the same time to be communicative (sweetly if you like.) . . . and all that, and yes, I have worked it out in my own way. In Town and City not as much as later, also. We can talk about it. Assured that I have “matured up to it” all-right; how could I miss?—I haven’t done anything but write for years and years, and you know I’m not stupid and unintelligent. Perhaps I can help you by pointing out pitfalls. As to the novel, I already handed it in to Scribner’s two weeks ago, and they’re reading it now; no word yet.

But here is news that will interest you a lot, I heard from Neal [Cassady]. Oh these are the sweet dark things that make writing what it is . . . Anyway I heard from Neal, and I had to fill out an application blank for his employer attesting to his character. Assured that I piled it on in the best Bill Burroughs letter-manner. I think I said that he would be of “great initial value to your organization and purposes,” etc. The job is as a brakeman on the Southern Pacific railroad. From which I assume—and I guessed right—that Neal got in trouble, got three months, and they’re getting him a job out of a jail agency of some sort. No peep out of Neal himself, however. The Southern Pacific is the most wonderful railroad in the world incidentally . . . on a Sunday morning, riding down through the sunny San Joaquin Valley of grapes and women-with-bodies-like-grapes, I reclined on a flatcar reading the Sunday funnies with the other boys, and the brakemen smiled at us and waved cheerful. It is the hobo’s favorite road. Anybody with any sense in California can ride between Frisco and LA endlessly on that road, once a week if they want to, and nobody will ever bother them. When the train stops at a siding, you can jump off and help yourself to fruit if you’re near a field. So wonderful Neal is working for a wonderful railroad, in the Saroyan country . . . (if there’s any beastly murderousness it’s not my fault or Neal’s or Saroyan’s.) The Santa Fe brakemen will kill you if they catch you and if they have enough clubs. But not the SP.

I had a season, Allen, I had a season. It lasted exactly four days. She was eighteen years old, I saw her on the street, was riven, and followed her into a roller skating rink. I tried to roller skate with her and fell all over the place. Young and beautiful of course.—Tony Monacchio, Lucien’s friend (and mine) was conversant with my beautiful season . . . He thought that the girl, Beverly, was too dumb for me, not vocal enough. I hated the thought of it . . . you can’t imagine how madly in love I was, just like with Celine [Young], only worse, because she was greater. But finally she rejected me because “she didn’t know me, she didn’t know anything about me.” I tried to get her over to my house to meet my mother for God’s sake but she was afraid I was trying to trick her, apparently. Sweet love softly denied. She thought I was some sort of gangster . . . she kept hinting. She also thought I was “strange” because I didn’t have a job. She herself has two jobs and works herself to a bone, and can’t understand what “writing” is. Tony Monacchio and I found Lucien dead drunk in Tony’s room after a party—on the night that Lucien was supposed to fly to Providence for his 2-weeks vacation. We helped him to the Air Lines bus. He was bleary-eyed, blind, wearing brown-and-white saddle shoes like a Scott Fitzgerald character of the 20s. I suddenly realized that Lucien is drinking too much after all and that Barbara [Hale]18 is not doing anything about it. I mean he was really sick. Tony said to him, “Jack’s girl is sweet and beautiful but dumb.” And Lucien, out of this dizzy sickness of his, said—“Everybody in the world is sweet and beautiful but dumb.” Allen, these are the things, these are the things, don’t worry about the theory of writing, not at all. Then Lucien thanked us for escorting him to the “airplane” as he called the bus, and there was a farewell. That afternoon my little girl rejected me. So now, how are you? How’s everybody in the sweet beautiful dumb world?

Jack

Allen Ginsberg [n.p., New York, New York?] to

Jack Kerouac [n.p., New York, New York?]

after May 18, 1948

Monday Night : 1:30

Dear Jack:

I got your letter Sat. evening—I had been in Paterson for a few days. I will be in this weekend (in N.Y.).

You seemed overly proud that it was “ancient material.” What I was saying in part (lesser part) was that it was not recognizable (to me in your prose) but but but. This is not the same old maturity that I (as [Bill] Gilmore) have been talking about before. This is something I wouldn’t have the slightest idea if Gilmore would understand and don’t care much. But you are right, perhaps it’s under my nose in you. This is a kick I don’t want to continue.

School is over and I have been reading Dante, which I have found very inspiring. I finished the Divine Comedy during the term, and am reading books including The Vita Nuova (New Life) [by Dante Alighieri]. I dreamed up an enormous tentative plan tonight, which I will tell you about. My interest in reading is the profit by other men’s experience. I sometimes find (only lately) authors talking directly to me, from the bottom of their minds. I think I am going to write a sonnet sequence. I want to read Petrarch and Shakespeare, Spencer and Sidney, etc. and learn about sonnets from beginning to end, and write a series on love, perfectly, newly conceived. I conceived the whole idea all at once seeing the first word in a title embedded in a page of the Vita Nuova: my poems have always been prophesied by their titles. That is, a poem often has a single “transcendent, personal, and serious idea” behind it, as a novel—a single image. I want to celebrate my “lovers” in all various manners, intellectually, wittily, passionately, raptly, nostalgically, pensively, beautifully, realistically, “soberly,” enthusiastically, etc., every possible perception fitted out in inwrought, clear, complex stanzas—including the one as yet undefined or un-stated mood, or better, knowledge, that I have and that at times you are aware that I ha

ve, no matter how silly I get. The title of this is: “The Fantasy of the Fair.” Just repeat it aloud, it carries the whole idea in it. One of the major ideas is the dynamic sense of “Lucien’s Face” which you once propounded to me and which I half understood at the time. I want to formulate it poetically, if possible as the end of the poem, but without any private or subjective, or N.Y. idea of L.I. [Long Island] use the name to bridge at the moment. I am talking about humanity, and beginning to try to write in eternity.

I have been enduring a series of troublesome dreams lately about Neal [Cassady]. Your notice comes at about the crisis of them, though it is not a passional crisis and is accompanied by no tempests of intellect. I wonder what he is doing in his eternity. I feel so far away from people, without loneliness, that I am rather happy now. [ . . . ]

I’m not worried about the theory of writing, I am only just vering the practice. The Doldrums are antiquated. For that reason I am sending poetry out for the first time. I got my first rejection slip from Kenyon; a note from J.C. Ransom, editor and poet: “I like very much this slow, iterative, organized and reflective poem. At times it’s like a sestina. Thank you for sending it. But still I think it’s not for us exactly. I guess we need a more compacted thing.”

Tristessa

Tristessa On the Road

On the Road The Dharma Bums

The Dharma Bums Maggie Cassidy

Maggie Cassidy Big Sur

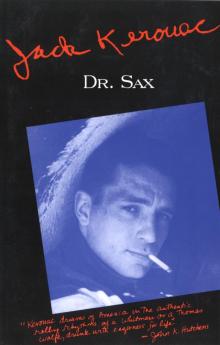

Big Sur Dr. Sax

Dr. Sax Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46

Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46 The Sea Is My Brother

The Sea Is My Brother The Town and the City: A Novel

The Town and the City: A Novel Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Desolation Angels: A Novel

Desolation Angels: A Novel Book of Sketches

Book of Sketches Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha

Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha The Electrocution of Block 38383939383

The Electrocution of Block 38383939383 Haunted Life

Haunted Life Visions of Gerard

Visions of Gerard Orpheus Emerged

Orpheus Emerged Book of Blues

Book of Blues The Subterraneans

The Subterraneans The Haunted Life

The Haunted Life The Unknown Kerouac

The Unknown Kerouac The Town and the City

The Town and the City Visions of Cody

Visions of Cody Atop an Underwood

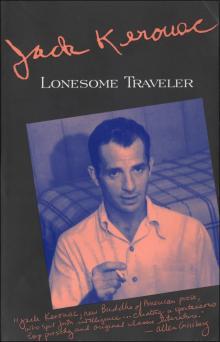

Atop an Underwood Lonesome Traveler

Lonesome Traveler Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg Vanity of Duluoz

Vanity of Duluoz Desolation Angels

Desolation Angels On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition)

On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition) The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel

The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel Wake Up

Wake Up The Poetry of Jack Kerouac

The Poetry of Jack Kerouac Doctor Sax

Doctor Sax