- Home

- Jack Kerouac

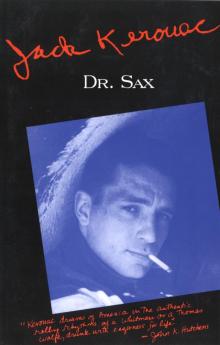

Doctor Sax Page 7

Doctor Sax Read online

Page 7

I always thought there was something mysterious and shrouded and foreboding about this event which put an end to childish play–it made my eyes tired— “Wake up now Jack–face the awful world of black without your aeroplane balloons in your hand”—Behind the thudding apples of my ground, and his fence that shivers so, and winter on the pale horizon of autumn all hoary with his own news in a bigmitt cartoon editorial about storing up coal for the winter (Depression Themes, now it’s atom-bomb bins in the cellar communist dope ring)—a huge goof to grow sick in your papers–behind winter my star sings, zings, I’m alright in my father’s house. But doom came like a shot, when it did, like the foreboding said, and like is implied in the laugh of Doctor Sax as he glides among the muds where my ballbearing was lost, by March midnight that overlaps with a glare mad of her bloodened sun-scapes in the set with the iron groo brush at dusk call fogs, across marshy surveys– Sax strides there soundless on the apple leaf in his mysterious dream-diving night–

When at sweet night I round all my kittens up, my cat, round my blanket up, he slips in, does exactly three turns, flops, motor runs, s’ ready to sleep all night till Ma calls for school in the morning–for wild oatmeal and toast by steaming autumn mornings–for the fogs shimmering up from G.J.’s mouth as he meets me in the corner, “Crise it’s cold!— the goddam winter’s got his big ass farting from the North before the ladies of the summer pick their parasols and leave.”

—Doctor Sax, whirl me no Shrouds–open up your heart and talk to me–in those days he was silent, sardonic, laughed in tall darkness.

Now I hear him scream from the bed of the brim–

“The Snake is Rising Inch an Hour to destroy us–yet you sit, you sit, you sit. Aieee, the horrors of the East–make no fancy up-carves to the Ti-bet wall than a Kangaroo’s mule eared cousin– Frezels! Grawms! Wake to the test in your frails– Snake’s a Dirty Killer–Snake’s a Knife in the Safe– Snake’s a Horror–only birds are good–murderous birds are good–murderous snakes, no good.”

Little booble-face laughs, plays in the street, knows no different– Yet my father warned me for years, it’s a dirty snaky deal with a fancy name–called L-I-F-E–more likely H-Y-P-E… How rotten the walls of life do get–how collapsed the tendon beam…

BOOK TWO

A Gloomy Bookmovie

SCENE 1 TWO O’CLOCK–strange–thunder and the yellow walls of my mother’s kitchen with the green electric clock, the round table in the middle, the stove, the great twenties castiron stove now only used to put things on next to the modem thirties green gas stove upon which so many succulent meals and flaky huge gentle apple pies have been hot, whee– (Sarah Avenue house).

SCENE 2 I’m at the window in the parlor facing Sarah Avenue and its white sands dripping in the shower, from thick hot itchy stuffed furniture huge and bearlike for a reason they liked then but now call ‘overstuffed’–looking at Sarah Avenue through the lace curtains and beaded windows, in the dank gloom by the vast blackness of the squareback piano and dark easy chairs and maw sofa and the brown painting on wall depicting angels playing around a brown Virgin Mary and Child in a Brown Eternity of the Brown Saints–

SCENE 3 With the cherubs (look closeup) all gloomy in their little sad disports among clouds and vague butterflies of themselves and somehow quite inhuman and cherub-like (“I have a cherub tells me,” says Hamlet to the Rosencranz and Guildenstern track team hotfooting back to Engla-terre)–(I’m rushing around with a wild pail in the winters in that now-raining street, I have a scheme to build bridges in the snow and let the gutter hollow canyons under … in the backyard of springtime baseball mud, I in the winter dig great steep Wall Streets in the snow and cut along giving them Alaskan names and avenues which is a game I’d still like to play–and when Ma’s wash is icy stiff on the line I march it down piecemeal on a side dredge into the drifts of the porch and shovel Mexican gloriettas around the washline merrygoround pole).

SCENE 4 The brown picture on the wall was done by some old Italian who has long since faded from my parochial school textbooks with his brown un-Goudt inks and inkydinky lambs about to be slaughtered by stem Jewish businesslike Mose with his lateral nose, won’t listen to his own little son’s wails, would rather–the picture is still around, many like it– But see close, my face now in the window of the Sarah Avenue house, six little houses in the entire dirt street, one big tree, my face looking out through dew-drops of the rain from within, the gloomy special brown Technicolor interior of my house where also lurks a pisspot gloom of family closets in the Graw North–I’m wearing corduroy pants, brown ones, smooth and easy, and some sneakers, and a black sweater over a brown shirt open at collar (I wore no Dick Tracy badges ever, I was a proud professional of the Shades with my Shadow & Sax)– I’m a little kid with blue eyes, 13, I’m munching on a fresh cold mackintosh apple my father bought last Sunday on the Sundaydriving road in Groton or in Chelmsford, the juice just pops and flies out of my teeth when I cool these apples. And I munch, and chaw, and look out the window at the rain.

SCENE 5 Look up, the huge tree of Sarah Avenue, belonged to Mrs. Flooflap whose name I forget but sprung God-like Emer Hammerthong from the blue earth of her gigantic grassy yard (it ran clear to long white concrete garage) and mushroomed into the sky with limb-spreads that o’ertopped many roofs in the neighborhood and did so without particularly touching any of em, now huge and grooking vegetable peotl Nature in the gray slash rain of New England mid-April– the tree drips down huge drops, it rears up and away in an eternity of trees, in its own flambastic sky–

SCENE 6 This tree fell down in the Hurricane finally, in 1938, but now it only bends and sinews with a mighty woodlimb groan, we see where the boughs tear at their green, the juncture point of tree-trunk with arm-trunk, tossing of wild forms upside down flailing in the wind,–the sharp tragic crack of a smaller limb stricken from the tree by stormhound-

SCENE 7 Along the splashing puddles of grassyard, at worm level, that fallen branch looks enormous and demented on its arms in the hail–

SCENE 8 My little boy blue eyes shine in the window. I’m drawing crude swastikas in the steamy window, it was one of my favorite signs long before I heard of Hitler or the Nazis– behind me suddenly you see my mother smiling,– “Tiens” she’s saying, “Je tlai dit queta bonne les pommes (There, I told you they were good the apples!)”—leaning over me to look out the window too. “Tiens, regard, l’eau est deu pieds creu dans la rue (There, look, the water’s two feet deep in the street)— Une grosse tempête (a big storm)— Je tlai dit pas allez école aujourdhui (I told you not to go to school today)— WS tu? comme qui mouille? (See? how it rains?) Je suis tu dumb?(Am I dumb?)”

SCENE 9 Both our faces peer fondly out the window at the rain, it made it possible for us to spend a pleasant afternoon together, you can tell how the rain pelts the side of the house and the window–we don’t budge an inch, just fondly look on–like a Madonna and son in the Pittsburgh milltown window–only this is New England, half like rainy Welsh mining towns, half the Irish kid sunny Saturday Skippy morning, with rose vines—(Bold Venture, when May came and it stopped raining, I played marbles in the mudholes with Fatso, they piled up with blossoms overnight, we had to dig em out for every day’s game, blossoms from trees raining, Bold Venture won the Derby that Saturday)— My mother behind me in the window is oval faced, dark haired, large blue eyes, smiling, nice, wearing a cotton dress of the thirties that she’d wear in the house with an apron–upon which there was always flour and water from the work with the condiments and pastries she was doing in the kitchen–

SCENE 10 There in the kitchen she stands, wiping her hands as I taste one of her cup cakes with fresh icing (pink, chocolate, vanilla, in little cups) she says, “All them movies with the old grandmaw in the West slappin her leetle frontiers boy and smackin him ‘Stay away from dem cookies,’ Ah? la old Mama Angelique don’t do that to you, ah?” “No Ma, boy,” I say, “si tu sera comme ga jara toujours faim (No Ma, boy if you

was like that I’d always be hungry)” “Tiens–assay un beau blanc d’vanilla, c’est bon pour tué (There, try a nice white one of vanilla, it’s good for you.)” “Oh boy, blanc sucre! (“. . . . .”) (Oh boy, white sugar!)” “Bon,” she says firmly, turning away, “asteur faut serrez mon lavage, je lai rentrez jusquavant’quil mouille (Good, now I’ve got to put away my wash, I got it in just before it rained)”—(as on the radio thirties broadcasts of old gray soap operas and news from Boston about finnan had die and the prices, East Port to Sandy Hook, gloomy serials, static, thunder of the old America that thundered on the plain)— As she walks away from the stove I say, from under my little black warm sweater, “Moi’s shfué’s fini mes race dans ma chambre (Me I’s got to finish my races in my room)”— ”Amuse toi (amuse yourself)”—she calls back —you can see the walls of the kitchen, the green clock, the table, now also the sewing machine on the right, near the porch door, the rubbers and overshoes always piled in the door, a rocking chair facing the oil heat stove–coats and raincoats hanging on hooks in corners of the kitchen, brownwood waxed panelling on the cupboards and wainscots all around– a wooden porch outside, glistening from rain–gloom—things boiling on the stove—(when I was a very little kid I used to read the funnies on my belly, listen on the floor to boiling waters of stove, with a feeling of indescribable peace and burble, suppertime, funnies time, potato time, warm home time) (the second hand of the green electric clock turning relentlessly, delicately through wars of dust)—(I watched that too)—(Wash Tubbs in the ancient funnypage)—

SCENE 11 Thunder again, now you see my room, my bedroom with the green desk, bed and chair–and the other strange pieces of furniture, the Victrola already to go with Dardanella and crank hangs ready, stack of sad thirties thick records, among them Fred Astaire’s Cheek to Cheek, Parade of the Wooden Soldiers by John Philip Sousa– You hear my footsteps unmistakably pounding up the stairs on the run, pleup plop ploop pleep plip and I’m rushing in the room and closing the door behind me and pick up my mop and with foot heavy pressed on it mop a thin strip from wall near door to wall near window–I’m mopping the race track ready–the wallpaper shows great goober lines of rosebushes in a dull vague plaster, and a picture on the wall shows a horse, cut from a newspaper page (Morning Telegraph) and tacked, also a picture of Jesus on the Cross in a horrible oldprint darkness shining through the celluloid—(if you got close up you could see the lines of bloody black tears coursing down his tragic cheek, O the horrors of the darkness and clouds, no people, around the stormy tempest of his rock is void–you look for waves–He walked in the waves with silver raiment feet, Peter was a Fisherman but he never fished that deep–the Lord spoke to dark assemblies about gloomy fish–the bread was broken … a miracle swept around the encampment like a flowing cape and everybody ate fish … dig your mystics in another Arabia. . .). The mop I am mopping the thin line with is just an old broomhandle with a frowsy drymop head, like old ladies’ hair at the hair stylists–now I am getting down briskly on my knees to sweep away with my fingertips, feeling for spots of sand or glass, looking at the fingertips with a careful blow,—10 seconds pass as I prepare my floor, which is the first thing I do after slapping the door behind me– You saw first my one side of the room, when I come in, then left to my window and the gloomy rain splattering across it-rising from my knees, Wiping fingers on pants, I turn slowly and raising fist to mouth I go “Ta-ta-ta-tra-tra-tra-etc.”—the racetrack call to the post by the bugler, in a clear, well modulated voice actually singing in an intelligent voice-imitation of a trumpet (or bugle). And in the damp room the notes resound sadly– I look goopy with self-administered amazement as I listen to the last sad note and the silence of the house and the rain click and now the clearly sounding whistle of Boott Mills or Goop Mills coming loud and mournful from across the river and the rain outside where Doctor Sax even now is preparing for the night with his dark damp cape, in mists– My thin trail for the races began at a cardboard inclined on books–a Parchesi board,—folded, to the Domino side to keep the Parchesi side from fading (precursor to the now Monopoly board with checkers on other side)—no wait, the Parchesi board had a black blank side, down the huck of this all solid and round raced my marbles when I let them slip down from under the ruler– Lined on the bed are the eight gladiators of the race, it’s the fifth race, the handicap of the day.

SCENE 12 “And now,” I’m sayin, as I bend low at the bed, “and now the Fifth Race, handicap, four year olds and up etc.”—”and now the Fifth Race of the gong, come on Ti Jean arrete de jouer and get on with the–they’re headed for the post, the horses are headed for the post”—and I hear it echoing as I say it, hands upraised before the lined up horses on the blanket, I look around me like a racing fan asking himself, “Say, it shore is gonna rain soon, they’re headed for the post?”—which I do— “Well son, better bet five on Flying Ebony the old gal’ll make it, she didn’t do too bad against Kransleet last week.” “Okay Pa!”—striking new pose—”but I see Mate winning this race.” “Old Mate? Nah!”

SCENE 13 I rush to the phonograph, turn on Dardanella with the push hook.

SCENE 14 Briskly I’m kneeled at the race-start barrier, horses in left hand, ruler barrier clamped down at starting line in right hand, Dardanelles going da-daradera-da, I have my mouth open breathing in and out raspily to make racetrack crowd noises–the marbles pop into place with great fanfare, I straighten em around, “Woops,” I say, “look–out—1-o-o-k-o-u-t no–NOPE! Mate broke from the starter’s helper–back he goes–Jockey Jack Lewis exasperated on his back–set em up straight now–the horses are at the post!’ —Oh that old fool we know that”- “They’re off!” “What? “They’re off!-hoff!” crowd sigh–boom! they’re off— “You made me miss my start with that talk of yours–and it’s Mate taking an early lead!” And off I rush following the marbles with my eyes.

SCENE 15 Next scene, I’m crawling along all stridey and careful following my marbles, and I’m calling em fast “Mate by two lengths”—

SCENE 16 POW flash shot of Mate the marble two inches ahead of big limping Don Pablo with his chipholes (regularly I held titanic marble-smashing ceremonies and “trainings” and some of the racers came out chipped and hobbled, great Don Pablo had been a great champion of the Turf, in spite of an original crooked slant in his round–but now chipped beyond repair–an uncommon tender fore hock, crock, wooden fenders of gloomy mainsmiths smashing up the horn in the horse’s hoof on gray afternoons on Salem Street when still a little horseshit perfumed the Ah Afternoons of Lowell-tragic migs frantic in a raw bloom of the floor, of the flowery linoleum carpet just drymopped and curried by the racetrack trucks— “Don Pablo second!” I’m calling in the same low Doctor Sax crouch—’and Flying Ebony coming up fast from a slow start in the rear-Time Supply” (red stripes on white), (no one else will ever name them), blam, no more time, I’m already leaning over with my arm extended to lean falling on the wall over the finish line and hang my face tragically over the pit of the wood homestretch in entryway with wide amazement and speechless–just manage, wide-eyed, to say— “-s-a-a-a-,”-

SCENE 17 The marbles crashing into wall.

SCENE 18 “—Don Pablo rolled over and crashed in–gee, chipped, he’s so heavy! Don Pablo-o!” with hands to my head in the great catastrophe of the “fans” in the grandstand. (One morning in that room there had been such glooms, no school, the first official day of racing, way back in the beginning, the dismal rainy 1934’s when I used to keep history of myself–started that long before Scotty and I kept baseball history of our souls, in red ink, averages, P. Boldieu, p., .382 bat, .986 field–the day Mate became the first great winner of the Turf, capturing a coveted misty prize of lost afternoons (the Graw Futurity) beyond the hills of Mohican Springs racetrack “in Western Massachusetts” in the “Mohawk Trail country”—(it was only years later I turned from this to the stupidities and quiddities of H.G. Wells and Mososaurs–in these parentheses sections, so (-), the air is free

, do what you will, I can–why? whoo?—) the gray dismal rains I remember, the tragic damp on my windowpane, the flood of heat pouring up through the transom near the closet, my closet itself, the gloom of it, the doom of it, the hanging balloons of it, the papers, boxes, smatterdurgalia like William Allen White’s closet in Wichita when he was 14—my yearning for peanut butter and Ritz crackers in the late afternoon, the gloom around my room at that hour, I’m eating my Ritz and gulping my milk by the wreckage of the day– The losses, the torn tickets, the chagrined footsteps disappearing out the ramp, the last faint glimmer of the toteboards in the rain, a torn paper rolling dismally in the wet ramps, my face long and anxious surveying this scene of gloomy jonquils in the floor-frat–that first bookkeeping graymorning when Mate won the Stakes and from the maw-mouth of the Victrola the electric yoigle yurgle little thirties crooners wound too fast with a slam-bash Chinese restaurant orchestry we fly into the latest 1931 hit, ukeleles, ro-bo-bos, hey now, smash-ah! hah! atch a tchal but usually it was just, “Dow-dow-dow, tadoodle-lump!”—”Gee I like hot jyazz”—

Snazzz!)

—but in that room all converted into something dark, cold, incredible gloomy, my room on rainy days and all in it was a saturation of the gray Yoik of Bleak Heaven when the sides of the rainbow mouth of God hang disfurdled in a bloomy rue–no color . . . the smell of thought and silence, “Don’t hang around in that stuffy old room all the time,” my mother had said to me when Mike came for our Dracut Fields Buck Jones appointment and instead I was busy running off the Mohican Futurity and digging back into earlier records of my antiquity for background material for the little newspaper story announcing the race … printed by hand on gloomy gray-green sheets of Time.

Tristessa

Tristessa On the Road

On the Road The Dharma Bums

The Dharma Bums Maggie Cassidy

Maggie Cassidy Big Sur

Big Sur Dr. Sax

Dr. Sax Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46

Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46 The Sea Is My Brother

The Sea Is My Brother The Town and the City: A Novel

The Town and the City: A Novel Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Desolation Angels: A Novel

Desolation Angels: A Novel Book of Sketches

Book of Sketches Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha

Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha The Electrocution of Block 38383939383

The Electrocution of Block 38383939383 Haunted Life

Haunted Life Visions of Gerard

Visions of Gerard Orpheus Emerged

Orpheus Emerged Book of Blues

Book of Blues The Subterraneans

The Subterraneans The Haunted Life

The Haunted Life The Unknown Kerouac

The Unknown Kerouac The Town and the City

The Town and the City Visions of Cody

Visions of Cody Atop an Underwood

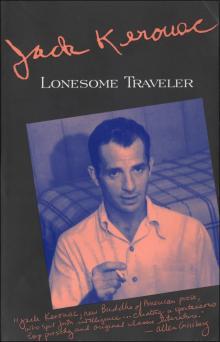

Atop an Underwood Lonesome Traveler

Lonesome Traveler Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg Vanity of Duluoz

Vanity of Duluoz Desolation Angels

Desolation Angels On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition)

On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition) The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel

The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel Wake Up

Wake Up The Poetry of Jack Kerouac

The Poetry of Jack Kerouac Doctor Sax

Doctor Sax