- Home

- Jack Kerouac

Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha Page 8

Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha Read online

Page 8

After the conversion of Mahae Kasyapa, walking in the path of earth Gotama Sakyamuni returned to the country where he was born, Gorakpur District, where his father King Suddhodhana reigned. Followed by his numerous Men of Saintship, yet advancing with the grave mysterious loneliness of the elephant, he came to within several miles of Kapilavastu where the sumptuous palace of his youth still stood, as unreal now, in his enlightened mirror-like reflection, as an indicated castle in a child’s tale designed solely to make children believe in its existence. The King heard of his arrival and came at once, eagerly concerned.

On seeing him he uttered these mournful words: “Thus, now I see my son, his well known features as of old; but how estranged his heart! There are no grateful outflowings of soul; cold and vacant there he sits.”

They looked at each other like people thinking upon a distant friend gazing by accident upon his pictured form.

Buddha: “I know that the King’s heart is full of love and recollection, and that for his son’s sake he adds to grief further grief; but now let the bands of love that bind him, thinking of his son, be instantly unloosed and utterly destroyed.

“Ceasing from thoughts of love, let your calmed mind receive from me, your son, religious nourishment such as no son has offered yet to father; such do I present to you the King, my father.

“The way superlative of bliss immortal I offer now the Maharajah; from the accumulating of deeds comes birth; as the result of deeds comes the recompense. Knowing then that deeds bring fruit, as the wheel follows the foot of the ox that draws the carriage, how diligently should you be to rid yourself of worldly deeds! how careful that in the world your deeds should be only good and gentle!

“But not for the sake of a heavenly birth should you practice gentle deeds but that by day and night, rightly free from thoughts unkind, loving all that lives and equally, you may strive to get rid of all confusion of the mind and practice silent contemplation; only this brings profit in the end, beside this there is no reality.

“For be sure! earth, heaven, and hell are as but froth and bubble of the sea.

“Nirvana! This is the chief rest.

“Composure! that the best of all enjoyments.

“Infinitely quiet is the place where the wise man finds his abode; no need of arms or weapons there! no elephants or horses, chariots or soldiers there!

“Banished, once for all, birth, age, and death.

“Subdued the power of greedy desire and angry thoughts and ignorance, there’s nothing left in the wide world to conquer!”

Having heard from his son how to cast off fear and escape the evil ways of birth, and in a manner of such dignity and tenderness, the King himself left his kingly estate and country and entered on the calm flowings of thoughts, the gate of the true law of eternality. Sweet in meditation, dew Suddhodhana drank. In the night, recalling his son with pride, he looked up at the infinite stars and suddenly realized “How glad I am to be alive to reverence this starry universe!” then “But it’s not a case of being alive and the starry universe is not necessarily the starry universe” and he realized the utter strangeness and yet commonness of the unsurpassable wisdom of the Buddha.

Accompanied by Maudgalyayana, the Blessed One visited the woman who had been his wife, the Princess Yasodhara in the Palace, for the purpose of taking his son Rahula on the road with him. Princess Yasodhara pleaded for the inheritance of the boy, who was now nineteen years old. “I will give him a more excellent inheritance,” said Buddha, and bade Maudgalyayana shave his head, and admit him to the Sangha Brotherhood.

After this they started out from Kapilavistu. In the pleasure gardens they came upon a party of Sakya princes, all cousins of Gotama, among them his cousins Ananda and Devadatta, who were to become, respectively, his greatest friend and his greatest enemy. Some years later when the Blessed One inquired of Ananda what it was that had impressed him in the Buddha’s way of life and most influenced him to forsake all worldly pleasures and enabled him to cut asunder his youthful sexual cravings so as to realize the true Essence of Mind and its self-purifying brightness, Ananda joyfully replied: “Oh, my Lord! the first thing that impressed me were the thirty-two marks of excellency in my Lord’s personality. They appeared to me so fine, as tender and brilliant, and transparent as a crystal.” This warm-hearted youth ranked but next to Maudgalyayana in brilliance of learning, but it was this combination of near-infatuated love for the Master and the superior erudite sharpness that prevented him from attaining to the states of equal-minded bliss experienced by the least of the bhikshus, some of them uneducated antiquity hoboes like Sunita the Scavenger, Alavaka the Cannibal (he had been an actual cannibal in Atavi prior to his enlightenment), or Ugrasena the Acrobat. Ananda became known as the Shadow, ever following the Blessed One’s footsteps, even when he paced, step for step and right behind, turning where he turned, sitting when he sat. After awhile it became habit for Ananda to serve his Master, such as preparing his sitting place, or going ahead to make arrangements in towns, providing him with little kindnesses when needed, constantly a companion and personal attendant, which the Blessed One accepted quietly.

In grievous contrast was the other cousin Devadatta. Jealous and foolish he joined the Order hoping to learn the Transcendental Samapatti graces that come after highest holy meditation so he could use them as powerful magic, even against the Buddha, if necessary, in his plans to found a new sect of his own. The Samapatti graces included Transcendental Telepathy. Devadatta’s evil avarice was not apparent in that first meeting in the gardens of Gorakpur. Looking upon all beings as equally to be loved, equally empty, and equally coming Buddhas it made little difference to the Blessed One what Devadatta harbored in his heart in the moment of ordination. Even later after Devadatta had made attempts on his life, as will be shown, with mighty sweetness the Exalted One blessed his inner heart.

The Teacher and his disciples moved on to Rajagaha where they were greeted by the immensely wealthy merchant Sudatta, who was called Anathapindika on account of his charities to the orphans and the poor. This man had just bought at an enormous price the magnificent Jetavana Park from a royal prince and built a splendid monastery of eighty cells and other residences with terraces and baths for the Buddha and his ordained disciples. The Blessed One accepted his invitation and made his abode there, right outside the great city of Sravasti. During the rainy seasons he came back to Rajagaha to stay in the monastery of the Bamboo Grove.

Most of the time he spent in solitude in the forest; the other monks sat apart, also practicing meditation, drinking in the example of the tremendous love-filled silence that emanated from the part of the forest where the Buddha sat meek on a throne of grass, long-suffering beneath the patience of the tree that sheltered him. Sometimes this life was pleasant (“Forests are delightful; where the world finds no delight, there the passionless will find delight, for they look not for pleasures”); sometimes it was not pleasant:

“Cold, master, is the winter night,” sang the monks. “The time of frost is coming; rough is the ground with the treading of the hoofs of cattle; thin is the couch of leaves, and light is the yellow robe: the winter wind blows keen.” But these men had roused and awakened themselves, as their forefather saints in the long tradition of the Indias, to the incomparable dignity of knowing that there are worse things than the stinging fly, the creeping snake, winter’s cold rain or summer’s scorching wind. Having escaped the grief of lust, and dissipated the clouds and mists of sensual desire, Buddha accepted food both good or bad, whatever came, from rich or poor, without distinction, and having filled his alms-dish, he then returned back to the solitude, where he meditated his prayer for the emancipation of the world from its bestial grief and incessant bloody deeds of death and birth, death and birth, the ignorant gnashing screaming wars, the murder of dogs, the histories, follies, parent beating child, child tormenting child, lover ruining lover, robber raiding niggard, leering, cocky, crazy, wild, blood-louts moaning for more blood-lust, utte

r sots, running up and down simpleminded among charnels of their own making, simpering everywhere, mere tsorises and dream-pops, one monstrous beast raining forms from a central glut, all buried in unfathomable darkness crowing for rosy hope that can only be complete extinction, at base innocent and without any vestige of self-nature whatever; for should the causes and conditions of the ignorant insanity of the world be removed, the nature of its non-insane non-ignorance would be revealed, like the child of dawn entering heaven through the morning in the lake of the mind, the Pure, True Mind, the source, Original Perfect Essence, the empty void radiance, divine by nature, the sole reality, Immaculate, Universal, Eternal, One Hundred Percent Mental, upon which all this dreamfilled darkness is imprinted, upon which these unreal bodying forms appear for what seems to be a moment and then disappear for what seems to be eternity.

Thousands of monks followed the Awakened One, and beat a track behind his path. On the last autumnal plain full-moon night the Exalted One took his seat in the midst of the assembly of monks under the canopy of heaven. And the Exalted One beheld the silent, calm assembly of monks and spoke to them as follows:

“Not a word is spoken, O Monks, by this assembly, not a word is uttered, O Monks, by this assembly, this assembly consists of pure kernel.

“Such is, O Monks, this fraternity of disciples, that it is worthy of offerings, of oblations, of gifts and homage and is the noblest community in the world.

“Such is, O Monks, this fraternity of disciples, that a small gift given to it becomes great, and a great gift given to it becomes greater still.

“Such is, O Monks, this fraternity of disciples, that it is difficult to find one like it in the world.

“Such is, O Monks, this fraternity of disciples, that one is glad to walk many miles to behold it, and even if it be only from behind.

“Such is, O Monks, this fraternity of disciples, such is, O Monks, this assembly, that, O Monks, there are among these disciples some monks who are Perfect Ones, who have reached the end of all illusion, who have arrived at the goal, who have accomplished the task, have cast off the burden, have won their deliverance, who have destroyed the fetters of existence, and who, through superior knowledge, have liberated themselves.”

And to the Awakened One who had come before him and to all Buddhas in all times throughout the universes he prayed the Heart of the Great Dharani, the center of his crowning Prayer, for the emancipation of the world from its incessant birth and dying:

“Om! O thou who holdest the seal of power

Raise thy diamond hand,

Bring to naught,

Destroy,

Exterminate.

O thou sustainer,

Sustain all who are in extremity.

O thou purifier,

Purify all who are in bondage to self.

May the ender of suffering be victorious.

O thou perfectly enlightened,

Enlighten all sentient beings.

O thou who art perfect in wisdom and compassion

Emancipate all beings

And bring them to Buddhahood, amen.”

As the Word of awakening spread around, the ladies cut off their hair, put on the yellow robe, took begging bowls, and came out to meet Buddha. No, he said, “As water is held up by a strong dyke, so have I established a barrier of regulations which are not to be transgressed.” But since even the Princess Yasodhara and his devoted maternal aunt Prajapati Gotami were among this elite group of earnest and fearless women, and Ananda with typical affectionateness and at the importunate insistence of Gotama’s aunt interceded so fervently in their favor, the Blessed One relented and the Sisterhood of Bhikshunis came into being. “Let them be subject and subordinate to the brethren,” he commanded.

“Even so,” spoke the Holy One, “their admission means that the Good Law shall not endure for a thousand years, but only for five hundred. For as when mildew falls upon a field of rice that field is doomed, even so when women leave the household life and join an Order, that Order will not long endure.” Coupled with this was his premonition of the troubles that came in after days when Devadatta rose up and used some of the nuns for his schemes.

The Great King Prasenajit, whose kingdom dwelt in mighty peace yet himself being beset with confusion and doubt after a falling-out with his erstwhile beloved queen, and wishing at this time to hear the good and evil law from the lips of the Honored of the Worlds, found the Buddha, approached him respectfully from the right side, paid his compliments, and sat down.

To King Prasenajit the Tiger of the Law said: “Even those who, by evil Karma, have been born in low degree, when they see a person of virtuous character feel reverence for him; how much rather ought an independent king, who by his previous conditons of life has acquired much merit, when he encounters Buddha, to conceive even more reverence.

“Nor is it difficult that a country should enjoy more rest and peace, by the presence of Buddha, than if he were not to dwell therein.

“Now then, for the sake of the great ruler, I will briefly relate the good and evil law. The great requirement is a loving heart! To regard the people as we do an only son; not to exercise one’s self in false theories, nor to ponder much on kingly dignity, nor to listen to the smooth words of false teachers.

“Not to vex one’s self by ‘lying on a bed of nails,’ but to meditate deeply on the vanity of earthly things, to realize the fickleness of life by constant recollection.

“Not to exalt one’s self by despising others, but to retain an inward sense of happiness resulting from one’s self, and to look forward to increased happiness hereafter resulting also from one’s own self.

“Hear, O Maharajah! Self be your lantern, self be your refuge, no other refuge! The Established Law be your lantern, the Established Law be your refuge!

“Evil words will be repeated far and wide by the multitude, but there are few to follow good direction.

“As when enclosed in a fourstone mountain, there is no escape or place of refuge for anyone, so within this sorrow-piled mountain-wall of old age, birth, disease, and death, there is no other escape for the world than the practicing of the true law by one’s own self.

“All the ancient conquering kings, who were as gods on earth, thought by their strength to overcome decay; but after a brief life they too disappeared.

“Look at your royal chariot; even it is showing signs of wear and tear.

“The Aeon-fire will melt Mount Sumeru, the great water of the ocean will be dried up, how much less can our human frame, which is as a bubble and a thing of unreality, kept through the suffering of the long night of life pampered by wealth, living idly and in carelessness, how does this body expect to endure for long upon the earth! Death suddenly comes and it is carried away as rotten wood in a stream.

“Thick mists nurture the place of moisture, the fierce wind scatters the thick mists, the sun’s rays encircle Mount Sumeru, the fierce fire licks up the place of moisture, so things are ever born once more to be destroyed.

“The Being who is Cooled, not lagging on the road of the law, expecting these changes, frees himself from engagements, he is not occupied with self-pleasing, he is not entangled by any of the cares of life, he holds to no business, seeks no friendships, engages in no learned career, nor yet wholly separates himself from it; for his learning is the wisdom of not-perceiving wisdom, but yet perceiving that which tells him of his own momentariness.

“The wise ones know that, though one should be born in heaven, there is yet no escape from the changes of time and the changes of self, the pernicious rules of existence even heavenly; their learning, then, is to attain to the changeless mind; for where no change is, there is peace.

“The changeless body of life immortal is offered all; it is the mind-magic-body (manomayakaya); all beings are coming Buddhas because all beings are coming no-bodies; and all beings were past Buddhas because all beings were past no-bodies; and thus, in truth, all beings are already Buddhas because all beings are

already no-bodies.

“For the possession of changeful body is the foundation of all pain.

“Conceive a heart, loathe lust; put away this condition, receive no more sorrow. For lust is change, lust is desires unequally yoked like two staggering oxen, lust is loss of love.

“When a tree is burning with fierce flames how can the little sister-birds congregate therein?

“The wise man, who is regarded as an enlightened sage, without this knowledge is ignorant.

“To neglect this knowledge is the mistake of life.

“All the teaching of the schools should be centered here; without it is no true reason.”

Hearing these words King Prasenajit went back home and reconciled with his queen. He became quiet and joyful. He had learned that the want of faith is the engulfing sea of ignorance, the presence of disorderly belief is the rolling flood of lust; but wisdom is the handy boat, reflection is the hold-fast by which to win access to the other shore and find eternal safety. But King Prasenajit was not yet enlightened nor wholly a believer in the Buddha, for in his joy and religious enthusiasm he now ordered sacrificial rites in order to obtain merit beyond the merit of the sermon.

The Blessed One was at Sravasti, in the Jeta grove in Anathapindika’s park. A number of monks having risen early and dressed and taken bowl and robe, entered Sravasti for alms. After their return they sought the presence of Buddha and told him of the preparations for a great sacrifice being arranged to be held for King Prasenajit. Five hundred bulls, five hundred bullocks, and as many heifers, goats, and round-horned rams were led to the pillar to be sacrificed, after which the slaves and menials and craftsmen, hectored about by blows and by fear, made the preparations with tearful faces weeping. Hearing of this evil murderousness, the Exalted One understood as ever that men were shamed and debased forever, and only because of ignorance.

Tristessa

Tristessa On the Road

On the Road The Dharma Bums

The Dharma Bums Maggie Cassidy

Maggie Cassidy Big Sur

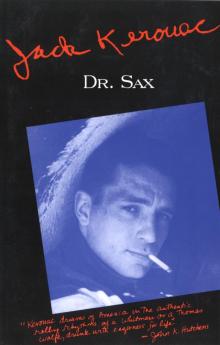

Big Sur Dr. Sax

Dr. Sax Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46

Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46 The Sea Is My Brother

The Sea Is My Brother The Town and the City: A Novel

The Town and the City: A Novel Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Desolation Angels: A Novel

Desolation Angels: A Novel Book of Sketches

Book of Sketches Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha

Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha The Electrocution of Block 38383939383

The Electrocution of Block 38383939383 Haunted Life

Haunted Life Visions of Gerard

Visions of Gerard Orpheus Emerged

Orpheus Emerged Book of Blues

Book of Blues The Subterraneans

The Subterraneans The Haunted Life

The Haunted Life The Unknown Kerouac

The Unknown Kerouac The Town and the City

The Town and the City Visions of Cody

Visions of Cody Atop an Underwood

Atop an Underwood Lonesome Traveler

Lonesome Traveler Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg Vanity of Duluoz

Vanity of Duluoz Desolation Angels

Desolation Angels On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition)

On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition) The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel

The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel Wake Up

Wake Up The Poetry of Jack Kerouac

The Poetry of Jack Kerouac Doctor Sax

Doctor Sax