- Home

- Jack Kerouac

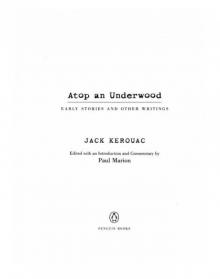

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Page 13

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Read online

Page 13

“Shore,” Pete would say. “Shore as yore standin’ here .... an’ now I reckon I’ll lope on to the shack and rustle me some grub .... Adios . . . . .”

Pete had a brother named Mike, who never said anything. He used to walk around with his long arms swinging regularly, his short legs straddling amazingly out of proportion, a huge noiseless stride that seemed forever going uphill. It has never been recorded or proven that Pete and Mike ever spoke to each other, although they were normal and friendly brothers. It’s just that they never thought of talking to each other .... it was merely a matter-of-fact thing that required no particular attention on the part of either one. However, we used to play basketball in the park with the two of them. Mike was always on one team, Pete on the other. It was a tremendous spectacle to watch them give each other the old hip . . . . . whack! ...... whap! .... each silent and red-faced with a comical, wordless anger. It was, however, their way of communicating to each other . . . . . whack! ...... whap! .... the old hip, a deft insinuation of the buttock at the right moment . . . . . whack! . . . . . whap! ...

In this little old neighborhood of mine lived a bunch of younger kids who used to fill the sunset hours with the uproar of their gunfights . . . . . taaah! . . . . taaah! . . . . taah! . . . . you could see them dart from barrels and dash heroically through a hail of bullets, blazing at both toy muzzles with Buck Jones abandon. One of these kids was Salvey.

One summer, he suddenly disappeared from these nightly battles, and two weeks later we discovered him, to our amazement, standing on the corner of the Variety Store with the “big guys,” smoking and spitting calmly.

Salvey used to go swimming with us to the Brook, and when he did the jack-knife dive off the grassy bank he looked like something you might call flapping fins. That’s how slender and how flexible he was. He was so loose that when he stood relaxed, his abdomen hung dejectedly . . . . . we named him “Cave-in.”

And then there was Mel, a brute of a boy with the power and roar of a gorilla. He was our hero, but it took Fouch to control his mind. Fouch used to get Mel all excited by doing a grotesque, half-squatting dance, adding to that several choice phrases and popping out his big almond eyes in a hypnotic stupefaction that swayed and maddened the boy bull. We were afraid to commit any foul deeds on Fouch, for fear he would unleash his monster and send him after us.

Mel, Fouch, and I used to go to the wrestling matches every week. It was great to sit there and watch the big hams grunt and groan in the throes of their enormous farce. The roped-in square was lost in a sea of cigarette smoke, and sometimes the wrestlers would throw the referee out of the ring.

However, Mel was a fine boy. He was a strict Catholic, and anyone that should show any signs of deviation was certain to incur his bull wrath. We kept our blooming metaphysics to ourselves.

There was still another neighborhood celebrity, back there in those gushing days. We called him Wattaguy, and he used to walk down the street with a ridiculous zeal that flung him along like a bobbing cork. Once when I had been playing alone with my imaginary horse-races in my room, I had heard him enter downstairs and ask my mother for me.

She was following instructions. “He’s out,” she said.

“I’ll take a look anyway,” he beamed, rubbing his hands vigorously. I put out my light and crawled under the bed. Wattaguy came into the room, turned on the light, and dragged me from under my hiding-place.

“What the hell are you doin’ there? Come on out. We’re playing chess!” And we did. Wattaguy was a swell kid, just the same.

And then there was the time we had a horse. A wealthy friend of my father’s had given it, a six-year-old mare, to myself and my sister. My chum Mike, who lived clear across the city, was nuts about horses. He practically boarded with us while we had it. One day, the horse broke loose from my yard and ran wild-eyed through the entire section. Mike and I chased it with a lasso, up the sandbank, down the street, along the river, up the street, and up the sandbank again. We finally lured the frightened beast with stable food and haltered him. It was a great day in the history of our neighborhood.

And Oh we did a million other things! We were kids, and we did everything . . . .

And these are but memories. The little neighborhood sleeps, three melancholy lamps shed their light, the cottages are squatted squarely on the familiar ground, shadows loom black and ghoul-like, starwealthy sky touches singing treetop, Augustcool I sit.

Hush . . . hush . . . wush ... hush . . . hush . . . wush ... shhhhhhhhhhhhh.....

I sit here remembering, and the trees sing me their farewell song.

I remember a lot of things. I remember exactly how the sun shone on Bill’s sandy hair one afternoon on the sandbank in the long-ago Summer gold; I remember also the shimmering rooftops in the heat, the distant sounds of afternoon—a woodsaw, someone hammering, a child’s shout, slamming door—I remember all this and how the sun burned down in yellow fire-shafts, how the sand under my “sneakered” foot was redhot . . . . . Oh Hell! I defy any man to refuse me! Look at that afternoon light, sometime back in the summer of 1933; look at the dry pebbled street, the crazy blaze-dance that melted its sparse tar, do not refuse me but look! look! look! . . . . . for here is a moment transpiring on the earth, at one place, at one time, a precious drop from Time’s ancient waterfall, and now it is long-ago and gone, forgotten and dead. The moment is over, has been over for eight years, yet I want it to return blazing! Yes, where is Bill today? Where?

Bill is in the Philippines, at the army base in Manila. He is all the way around the side of the world, and although the world turns, we never meet. Yes, Bill is in the Philippines, and today the sunblaze is yet upon his sandy hair. I sit here on a porch step in Massachusetts, in the middle of the night, August 1941. The sunblaze is yet upon his hair, but is it precisely the same sun of eight years ago in New England? Is it? Is it? And there is the irrefragable damnation of the whole brutal fact, there is the curse of Time, there is the song of the trees and the tear that surges at the burning gates!! ..... because it is not precisely the same sun of eight years ago in New England, it is not! it is not! and I cannot get to understand it!!

What is this thing Time?

Fouch is still living across the street, and tonight he is sleeping while the trees, high and dark and magnificent in the night, bend sadly and sing softly and Fouch hears them long through the night. Time! Fouch is not a young man, and he smokes cigarettes with an exasperated scowl. He sits in his kitchen at night and stares angrily at the green walls. His mother reads the Greek Bible, her lips silently mouthing the beautiful words. Yes Thalatta! Always Thalatta!

Why Time?

And tomorrow morning, with the swift and clean dawn, the truck will come and be loaded. Then, I shall sit in the back and watch the neighborhood as we roll away forever. My home and my land . . . .

Ah well. Remember the child: In partaking, question not. Question not, you fool.

Hush . . . hush . . . wush .... shhhhhh .... cool breeze and tree song . . . It is all over, it is all over . . . .

But I have been rich in days. Oh yes, I have been rich in days. They have tumbled down upon me, one upon the other, and are still tumbling today. It is true that I have to pull up my stakes and roll along, that I have to tear up my heartroots, but it is also true that I have been very very rich, and shall be very very rich, for the days do tumble, one upon the other.

And whatever is to come, I am content, for I have been rich in days, and shall be rich in days. I guess it is the same way with my country . . . . America too is rich. America is rich in years, ripe with generations. Whatever is to come, she too will be content, for she has been rich and will be rich. In her great wealth she will thrive. In my great wealth I shall thrive. The days have been golden because gold has been put into them. The days will be golden because gold will be put into them. This is Manifesto, simple and priceless. It is good to be rich. It is invincible to be rich.

And now, from the farmyards in back of my

neighborhood comes the scrawny-throated fanfare of a rooster, clear and clean. Dawn cometh. The first bird blurts his tiny twit. In the East appears the dirty grey vanguard of a new day. Wavy blankets of ghost mist cling to the still dark ground. I feel the chill of dew. And with all that, there is the serenade of my trees, tall dark trees singing way up there in the breeze, looking down at me sadly, farewell, farewell. A million tender rustlings, a vast soft song from my boyhood trees.

I look up at the trees, staring into their sorrowful profusion of night-green: “So long trees. I’ve got to move along,” I whisper to them. “So long . . . . . so long . . . . . oh so long . . . .”

And now I tell you I am weeping, quietly and without tears . . .

That old swishing song.

[I Have to Pull Up My Stakes and Roll, Man]

This is a later and longer version of an extended riff in the original manuscript of “Farewell Song, Sweet from My Trees,” from August 1941. The passage is the narrator’s answer to the Merrimack River’s question “Hey, who the hell are you?” as he prepares to leave his neighborhood of many years. The first version concludes: “I am of the American temperament, the American temper, the American tempo, river. And I tell you I am not Socrates wearing a robe, nor Shakespeare in breeches, but I am a poet in trousers, hat, shirt, coat, shoes, socks and my hair is combed, parted on the left side, I can jive a little bit, I play football and baseball, I go out with dames and I love America. That’s who I am. ”

I have to pull up my stakes and roll, Man. I’ll tell you what I am, first. I am part of the American temper, the American temperament, the American tempo. I wear trousers, (and with the latest trend) I wear long suit-coats, I try to get hold of the looser collars, the trickier ties; I aim to be a dapper man. That’s what I look like; and maybe sometime you’ll catch me with a turned up hat, Joe College himself, in the flesh.

I don’t wear robes, cloaks, nor breeches. I’m not Socrates, I’m not Shakespeare, I’m not Goethe. I’m Kerouac. And I’m in the 20th Century, 1941 A.D., right now. I am a poet, a philosopher, and I base my theories on science, of which I am quite ignorant, if not stupid. But I am no jerk, I assure you. I don’t write verse, I write poetry. And I am no jerk, because I know that I am part of the American temperament, I love swing bands with a terrific bucket man (drummer), and I love to have these bands dish out life and bite and beat (a steady beat, like Krupa’s, that rocks the dance floor with soul and precision) and I love to see those jitterbugs and their subtle bounce with the rhythm, their women who step quick and jerkily and spin with their jitterbug gams showing up to the garters, I love America and I love to look at those jitterbugs who let their hair grow long and sleek, with a knockout dazzling wave; their wide-brimmed, low-crowned hats (3 ¼ inchers); their pegged trousers with high belts; their swaggering walk, the way they smoke, the way they sensationalize, show off, the way they let you know about it, the way they click their shoe heels, the way they look around with a broad sweep and take in everything, pedestal themselves, talk good and audibly, expose themselves and turn the world into the blare of bands, the jive, the women-drink-smokes-debauchery-you thick bastard-Ho Ho-Make me know it, Dorsey, Make me know it!!!!!

Yes, I have to pull up my stakes and roll, and I told you about one part of the American temper because I am part of all of it.

I love a retired Yale professor; I love the jig bands (colored); I love André Kostelanetz and his sobbing string section; I love a street in Vermont, dusty and lined with discolored shacks; I love Boston’s Back Bay; I love the Daily Mirror; I love the C.C.C. camps in Colorado; I love Miami and all the chiselers down there; I love Saratoga’s race track, the Travers stakes, the Cup, (I remember Discovery vs. Granville, I remember Whirlaway, I also remember Aristides and the Derby, and after him Domino, Old Rosebud, Regret, Clyde Van Dusen, Johnstown.) Oh, yes, Man, I’m no jerk; I know my country, my onions, I know I’m part of the temper. I love Joe DiMaggio and the song about him, Les Brown’s arrangement; I love the cyclotrons at Columbia and Notre Dame; I love William Randolph Hearst; I love Broadway, and Beacon Street in Boston, Philadelphia in an October twilight and the flash and excitement of an intersection; I love Carnegie Hall; I love Brooklyn, 293 State Street and the Flatbush, Bainbridge Avenue, the Bridge, Coney Island; I love New England, I tell you I do; I love the dopes who argue on Times Square, Boston Common, on street corners in ‘Frisco, WallaWalla, Denver, Waco Texas; I love America; I love its tempo; I love the Navy Yard in Portsmouth, the Marine Base in Virginia; I love Hollywood (don’t get me wrong) and its Walter Pidgeon, its Brenda Marshall, its Boyer and Garbo and Gary Cooper and Edmund O’Brien, directors Ford, Sturges, Welles, Rita Hayworth (o man), I love its movies its people its personalities its Technicolor; I love New York, the New Yorker, Esquire for Men, Life, Time, the Atlantic Monthly, published in Concord, N.H.; I love New Haven, Yale, Hotel Taft, the trolleys and the beaches and the air-cooled theatres, the distinguished elms singing over houses austere; I love Estes Park, Colorado, the dirt street and wooden sidewalks and mountains; I love Arizona, the dude ranches; I love Chicago, the suburbs, Albert Halper—“kernels, pop, pop, pop for dear old Chicago . . . . . my arms are heavy, I’ve got the blues; there’s a locomotive in my chest and that’s a fact.” ; and I love Asheville, N.C. with the people sitting on the porches in the summer nights listening to the trains shriek in the valleys, and little Tom Wolfe sitting on his porch steps, listening, seething, “a locomotive in his chest.”; yes I love Saroyan and Fresno (the ditches in the fields, the vines, the Assyrian barbers, the flying young men on the trapeze, the Uncles Melik, Jorgi, etc. the Beautiful People); I love America, yes I do. I love the White Sox, the Dodgers, Ted Williams and Pete Reiser; I love America, I tell you I do.

Odyssey (Continued)

A series of short uneventful rides, and I find myself standing by the side of the road just over the Connecticut border. I am shaded by a natural wall which has been cut to make way for the road. Across the street are grass and trees, and up to the right, a nice little house. The sky is very blue.

It is so nice here that I feel like staying here forever, or at least for the night. But I must carry on in order to get home. Home spells comfort and security. This place spells poetry, ants in your clothes, and hunger.

To be exact about this writing game, now, let’s face it: A writer wants to cut a slab out of the whole conglomerate mass-symphony of nature and life and present it to his readers. Why? Because, Art is a readjustment of perception, from physical actuality to a perception expressed by the artist. This trip of mine occurred during the vast ant-rush of that day in May; it was a sequence, and ran from New York to Lowell, and took 12 hours. But now I am presenting it to my readers in the form of Art, so that their cognizance of this sequence is readjusted from reality to art. Why does the human being insist on presenting reality through an artistic and expressive medium? Why doesn’t he let well enough alone? Why should he express Life, through Art? Since the cavemen did it themselves, carving crude images of animals on stone, I am concluding that man is making an attempt to intensify consciousness, which is a very religious thing to do. Art, therefore, is in one measure religion. That may be why the Catholics like to call Art the language of God, or the such. But I say that Man, seeing Life about him, desires to express himself about this phenomena, and in so doing, exercises what is probably the only differentiating faculty between human and brute: That of Art, the act of readjusting perception, from reality to a new objectification and revaluation, thus exhibiting a religious desire to worship what we have about us, which is Life.

This settled, the writer now sets forth to document reality.

Well, I got a ride from a man who loved books and music. He recited William Cullen Bryant and praised Sir Walter Scott and Stevenson and Reid. He drove slowly and talked about himself. It was amazing, riding in a sleek car with a tender soul who loved the romance of Scott through streets strewn with realism—filling stations, stores, hydrants, straw hats, window fronts

, no sign of Ivanhoe nor Rebecca.

[At 18, I Suddenly Discovered the Delight of Rebellion]

Kerouac revisited this handwritten piece in 1945 and added the last four lines, beginning with “at 19.”

At 18, I suddenly discovered the

delight of rebellion—and was

drunk with it 1 ½ years, not

knowing how to wield this mad

thing, being more or less wielded

by it. Saroyan sparked it—

indolent, arrogant Saroyan. It

ruined my first College year.

But after the drunken stage,

I shortly gathered up my reins

and began to direct those daring

white steeds of rebellion into

a more constructive direction—

into a direction that was

bound to be the beginning of

ultimate, complete development

& integration.—at 19 1941

at 23, in 1945, what can

I add?

Or, perhaps, at 74 in 1996?

Observations

What more do I want but a meal when I am hungry, or a

bed when I am weary,

or a rose when I am sad?

What more does one need in this world but the few joys

that are afforded

him by this earth, this rich bursting earth, that flushes

with bloom each

Spring, and leases its luxury of wet warmth to us for a

glorious summer?

Tristessa

Tristessa On the Road

On the Road The Dharma Bums

The Dharma Bums Maggie Cassidy

Maggie Cassidy Big Sur

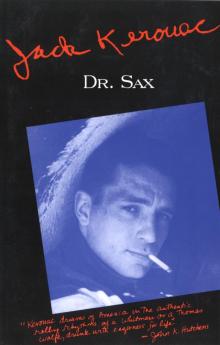

Big Sur Dr. Sax

Dr. Sax Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46

Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46 The Sea Is My Brother

The Sea Is My Brother The Town and the City: A Novel

The Town and the City: A Novel Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Desolation Angels: A Novel

Desolation Angels: A Novel Book of Sketches

Book of Sketches Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha

Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha The Electrocution of Block 38383939383

The Electrocution of Block 38383939383 Haunted Life

Haunted Life Visions of Gerard

Visions of Gerard Orpheus Emerged

Orpheus Emerged Book of Blues

Book of Blues The Subterraneans

The Subterraneans The Haunted Life

The Haunted Life The Unknown Kerouac

The Unknown Kerouac The Town and the City

The Town and the City Visions of Cody

Visions of Cody Atop an Underwood

Atop an Underwood Lonesome Traveler

Lonesome Traveler Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg Vanity of Duluoz

Vanity of Duluoz Desolation Angels

Desolation Angels On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition)

On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition) The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel

The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel Wake Up

Wake Up The Poetry of Jack Kerouac

The Poetry of Jack Kerouac Doctor Sax

Doctor Sax