- Home

- Jack Kerouac

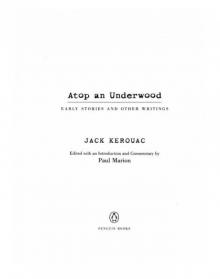

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Page 14

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Read online

Page 14

What more do I want but a woman when I am in passion,

or a glass of water

when I am thirsty, or music when I am lonely?

Why, I need not your sumptuous sitting room, nor your

full-vistaed garden!

Nor your wainscotted bedroom with overhanging canopy

and oils! All I need

is my little den, with a window to let the sun shine in,

and a shelf of

books, and a desk, and something to write with, and

paper, and my soul:Where can I find my soul?

In solitude said my friend, in solitude.

Yes. I have found my soul in solitude.

No, I don’t want riches! This has been said so many

times before. And

when I say the world is bursting with plenty, I know the

starved millions

will laugh: but I shall laugh with them and overthrow: I

know whereof I

speak: I am not a prophet, I am, like Whitman, a lover.

Whitman, that

glorious American! Barbellion, who will go with you,

anywhere, any time,

any fashion, for nothing, for everything. Come, I will go

with thee,

said Whitman: Whitman, the underrated, the forgotten,

the laughed-at,

the homosexual, the lover of life.

How shall I sing?

I shall sing: I shall record the misery, observe on it, and point

out how to abolish it. Blah.

Definition of a Poet

In 1941 Kerouac wrote: “You say, all poets like to kick. And this one here, Jack Kerouac, wants to kick in an original manner [. . . .]” Over and over in his early writings he refers to himself as a poet. To Kerouac, the poet was the ideal, the highest form of a writer, the artist-writer, of whom he wrote: “Their use lies in being able to erect structures of thought for mankind. ” He admired Walt Whitman, whom he credited with shaping “a living philosophy for his fellow countrymen.” He described Whitman as his “first real influence” and the reason he decided to hit the American road.

Young Kerouac experimented with poetry in all forms, but traditional verse forms did not suit him. In 1940 he explained why: “I feel that the words are put backwards. I’d rather have simple prose-poetry, to the point, concise, and more digestible. Outside of that, poetry is sublime. Poets are happy people, because they too are sublime.” He later added a few original forms to the array of poetic forms, including the “pop,” a three-line American or Western haiku without syllable restrictions, and the “blues,” which he defined as “a complete poem filling in one notebook page, of small or medium size, usually in 15-to-25 lines, known as a Chorus, i.e., 223rd Chorus of Mexico City Blues in the Book of Blues. ” Kerouac connected the blues and poetry, as does contemporary American poet Charles Simic, who writes: “The reason people make lyric poems and blues songs is because our life is short, sweet, and fleeting. The blues bears witness to the strangeness of each individual’s fate.”

A poet is a fellow who

spends his time thinking

about what it is that’s

wrong, and although he

knows he can never quite

find out what this wrong

is, he goes right on

thinking it out and writing

it down.

A poet is a blind optimist.

The world is against him for

many reasons. But the

poet persists. He believes

that he is on the right track,

no matter what any of his

fellow men say. In his

eternal search for truth, the

poet is alone.

He tries to be timeless in a

society built on time.

America in the Night

1

Listen!

Kroooaaooo! Krrooooaaooooo!

‘Tis the train whistle, now, in the night,

Kroooooo!

I’m on a train, and I’ve got to whistle too....

The real, the true America,

Is America in the night.

The guileful sleep, guile-less;

The egotists sleep, ego-less;

The timid sleep, fear-less.

Across the midnight face of America—

They sleep...

2

The real, the true America,

Is America in the night.

3

What is a youth?

I see one now—he is the youth of ages.

Frowning silently, he smokes—

A soldier in Alexander’s legions?

Quietly, he adjusts his regalia.

A young driver of Arabian caravans?

He yawns in the night, then listens:—

Krooooaaoooo.... !!

Of the fleet of Nelson?

A Tatar? A young soldier of Kublai Khan’s?

A crusader? The young Iroquois warrior?

A black defender of Khartoum?

Yank in France?

No matter—they are one, all are one.

And the same—the youth of ages.

An American sailor.

With me he plies the black waters of night,

Aboard the good ship S.S. America.

4

Red, white and blue they say?

America?

Don’t kid me, I say to they:—

America is blue

Right through—

Blue!

Improvise, black saxist, improvise!

Tell them with your black soul

That America is blue,

That America is the blues.

Play that throbbing tremolo—

Let me stand beside you, approving.

Bring him a soap box,

Let him stand up and play the blues.

Kroooaaaooooo!

5

Sibelius, tell us about Nature!

And you brave Waldo—

And thou also Thoreau.

Tell us about the dark forest in the night—

Patient, untelling, and wise.

And you Gershwin, and you Runyon—

Tell us about New York town . . .

In the night, in the night.

They tell me God made night to sleep—

Zounds! My dawn is in the West!

The darkness is over the land,

And the melancholy lamps glimmer,

And the train thunders through . . .

In the night.

Krooooaaooo!

6

Sandburg, Wolfe, Whitman, and Joe—

They all work for the railroad.

Sandburg, Wolfe, and Whitman sing—

While Joe pulls that old whistle string:—

Krooooaaoooo! Krooooaaooo!!

Lordy but they’re blue—

—Those lovers of the blues!

Woman Going to Hartford

I see the burnished

tenderness of the

countryside. Summer

is over, and that great

thrill I missed; next

summer, then.

Meanwhile, the tender

char in the sky.

Old earth, old old

earth. In the city,

leaves, air, sad people,

something old & lost.

Soon—winter,

My child—in the

park, tawny grass,

fiery tree, wind,

cold wind about his

little scarf. Does

he wonder too?

What, Oh what is

it?

Something old & lost,

Madam. Old earth, old.

Old Love-Light

October was a time of year packed with meaning for Ker-

ouac, even as a young man, as is illustrated in the two fol-

Lowing pieces. “I Tell You It Is October”

calls to mind

Thomas Wolfe’s October rhapsody that opens Book III in

Of Time and the River, with Eugene Gant back home af-

ter his father’s death. Kerouac later wrote in On the Road:

“In inky night we crossed New Mexico; at gray dawn it

was Dalhart, Texas; in the bleak Sunday afternoon we

rode through one Oklahoma flat-town after another; at

nightfall it was Kansas. The bus roared on. I was going

home in October. Everybody goes home in October. ”

The railroad buildings, dingied

by scores of soot-years,

thrusting their ugly rears

at your train window, are

a sign of man’s decay.

Once, I took a train

instead of a bus. A bus

takes you on a highway

lined with filling stations

& lunchcarts. A train

runs smack through the

forest. I wanted to

study the forest in October

and I took a train.

It was astonishing to read

what I read about October

the following day. I thought

I had it all figured out—

I thought the lonely little

houses, lost in the middle

of great tawny grass,

shaggy copper skies and

mottled orange forests, were

full of fine humanity that

I was missing. Instead, the

writer informed me that

it was chlorophyll that

colored the leaves. I

thought I had all the

significance of October

under my hat & pasted.

I thought that October

was a tangible being,

with a voice. The

writer insisted it was

the growth of corky cells

around the stem of the

leaf. The writer also

said that to consider

October sad is to be

a melancholy Tennysonian.

October is not sad, he

said. October is falling

leaves. October comes

between Sept. & Nov. I

was amazed by these facts,

especially about the

Tennysonian melancholia. I

always thought October was

a kind old Love-light.

I Tell You It Is October!

There’s something olden and golden and lost

In the strange ancestral light;

There’s something tender and loving and sad

In October’s copper might.

End of something, old, old, old . . .

Always missing, sad, sad, sad . . .

Saying something . . . love, love, love . . .

Akh! I tell you it is October,

And I defy you now and always

To deny there is not love

Staring foolishly at skies

Whose beauty but God defies.

For in October’s ancient glow

A little after dusk

Love strides through the meadow

Dropping her burnished husk.

It may be that I am mad, sir:

Or perhaps hope in vain . . .

But Oh! October is sad, sir,

As mournful as midnight rain.

The melancholy frowse of harvest stacks,

The tender char of morning skies,

The advance of Emperor October,

Father! Father!

Father November of the sombre silver,

Oh I tell you it is October!

[Here I Am at Last with a Typewriter]

Written on October 13, 1941. In the Saroyan story “Myself upon the Earth” from the 1930s, the narrator longs for his typewriter, which is tied up in a pawnshop: “After a month I got to be very sober and I began to want my typewriter. I began to want to put words on paper again. To make another beginning. To say something and see if it was the right thing. But I had no money. Day after day I had this longing for my typewriter.”

Here I am at last with a typewriter, a little more the hungrier, a little less the hungrier. There are some kinds of hunger, and there are other kinds of hunger.

As I write the first paragraph, it occurs to me that the print of this typewriter is similar to the print of a typewriter which I used in College, exactly one year ago. This is a thing which astonishes me no end, but affects you not. But the fact remains, here I am, one year later in life, with the same kind of typewriter, only the letters I put down are different, with more truth, sanity, health, background, and backbone than the old ones. When I was in college, I used to write for the fun of it. Now I’m in dead seriousness.

I see by the papers, and by Thomas Wolfe, that America is sick. This is a bad state of affairs, and it is being covered up by a lot of talk about hopeless Europe. Because Europe is hopeless at the moment doesn’t mean that America is to overlook her own defects. The National Defense move, a huge gesture on the part of a great nation for the benefit of a huge war, brings to my mind one amazing fact: Why didn’t we ever make such a tremendous drive for the sake of good things, rather than war? Why do huge movements such as this National Defense emergency have to be huge simply because they are propelled by greed? Why did our movement for American reconstruction measure up to this movement for war like a Lilliputian flea to a Brobdignagian dinosaur? (I’m talking about the W.P.A. and the National Defense?) It certainly makes you feel like vomiting, sometimes, in true Woollcott contempt. America is sick as a dog, I tell you. That’s why, with my new typewriter and a lot of yellow paper, I am grown dead serious about my letters, my work, my stuff, my writing here in an American city (Hartford). I will talk all about life in the 20th Century, and about America’s awful sickness and about some individual sickness I see in men and about good things in this life, namely, books, October skies, other varied weathers, women, Johnny Barleycorn, the Love of Man, a warm roof. I am alone in this boomtown, you see, but I am not silly. I am not going to rent a cheap room and starve. I’m going to rent a nice little halfcheap room, and starve halfways. That’s because I have a good job, and those silly guys didn’t, the suckers. (The lovely, the poor, the great suckers who in their solitary suffering and complaint, have added a jot of truth to America’s small pile of the stuff.)

Oh, yes, I am about to see life whole . . . . man’s travails, man plying his self-made civilization, man’s decay, man’s dignified despair and nobility. I am about to see it and smell it and eat it. It is going to be fine for me, I tell you. Fine for me, either way.

I am a writer, and thus it will prove valuable for me to study this place. However, before I start writing in dead seriousness, I want to add one thing. One of the remedies for American sickness is humour—there isn’t enough of it to go around—and I think it ought. to be fed to the people. This kind of humour, for instance:

You are sitting on a stone wall in the city, watching the people go by. It is midafternoon, and two little kids come up and ask you if you work in a filling station. After you say yes, you look back to the street, and everything has turned comical. The answer is the kids. Kids are not hankerers, they are just happy living men. Perhaps this may sound childish, but the children themselves will vouch for me. I know a guy who sees something comical in everything, but he also goes too far. I just thought I’d let you know. Remember humour.

Ha ha ha.

It’s a great thing.... it’s irony, and add to it pity. Pity and irony, America, pity and irony. Stuff as old as the Bible.

[Atop an Underwood: Introduction]

Immediately following this typed introduction to Atop an Underwood, on the same sheet of paper, is Kerouac’s short story “The Good Jobs.” He later recorded the introduction as “1941, October, Hartford,” without the specific day noted. It is likely that he wrote the introduction soon after establishing himself i

n Hartford with a job at an automobile service station, a room, and a rented Underwood typewriter. He worked the clay of that real-life experience as he wrote the 1968 version of Vanity of Duluoz: “...when I came home at night tired from work, after eating my nightly cheap steak in a tavern on Main Street, came in and started to write two or three fresh stories each night: the whole collection of short stories called ‘Atop an Underwood,’ not worth reading nowadays, or repeating here, but a great little beginning effort. [...]”

Kerouac describes himself “writing little terse short stories” in the mold of Saroyan and Hemingway. However, the stories composed in Hartford, and he claims to have written two hundred in about eight weeks, were rarely stories in the conventional sense, with a setting, plot, characters, and dialogue. Reading Saroyan and Hemingway would have given Kerouac a sense of flexibility with the form of a story. For example, Saroyan writes: “Do you know that I do not believe there is really such a thing as a poem-form, a story-form or a novel-form. I believe there is man only. The rest is trickery. ” The bursts of prose poetry also bring to mind Whitman’s Civil War writings in his Specimen Days. Whitman drew on “impromptu jottings” in notebooks for those accounts.

The term story better suits the Hartford work if we think of Kerouac’s using it as a journalist might have, in a newspaper or magazine story, the product of a reporter. Most of the time he was reporting on his own life, filing dispatches to the world desk from his personal cultural front. He was an old-time “newsie” with his bulletins, columns, and stories. He would give himself an assignment, then spin a piece of yellow paper into the Underwood, and start chewing up the blank sheet like a man devouring an ear of native corn. He often filled the sheet of paper top to bottom and margin to margin. There was barely enough space to contain his overflowing mind, so he wrapped up the thought and punched in the final jk on the last line—and you imagine him reaching for another piece of paper to start a new line of talk. He uses the page as a compositional field in the same way he turned the American dime store pocket notebook page into the ultimate pragmatic poetic form: end of the page, end of the blues chorus.

Tristessa

Tristessa On the Road

On the Road The Dharma Bums

The Dharma Bums Maggie Cassidy

Maggie Cassidy Big Sur

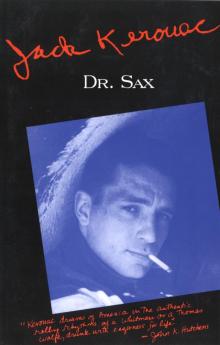

Big Sur Dr. Sax

Dr. Sax Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46

Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46 The Sea Is My Brother

The Sea Is My Brother The Town and the City: A Novel

The Town and the City: A Novel Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Desolation Angels: A Novel

Desolation Angels: A Novel Book of Sketches

Book of Sketches Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha

Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha The Electrocution of Block 38383939383

The Electrocution of Block 38383939383 Haunted Life

Haunted Life Visions of Gerard

Visions of Gerard Orpheus Emerged

Orpheus Emerged Book of Blues

Book of Blues The Subterraneans

The Subterraneans The Haunted Life

The Haunted Life The Unknown Kerouac

The Unknown Kerouac The Town and the City

The Town and the City Visions of Cody

Visions of Cody Atop an Underwood

Atop an Underwood Lonesome Traveler

Lonesome Traveler Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg Vanity of Duluoz

Vanity of Duluoz Desolation Angels

Desolation Angels On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition)

On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition) The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel

The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel Wake Up

Wake Up The Poetry of Jack Kerouac

The Poetry of Jack Kerouac Doctor Sax

Doctor Sax