- Home

- Jack Kerouac

Visions of Gerard Page 2

Visions of Gerard Read online

Page 2

“Yes, why—why do men make traps for little mice?”

“Because they eat their grain.”

“Their old grain.”

“It’s grain that’s in our bread—Look here, you eat it your bread? I dont see you throw it on the floor! and you dont make passes with the dust in the corner!”—Passes were the name Gerard had invented for when you run your bread over gravy, my mother’d do the soaking and throw the passes all around the table, even to me in my miffles and bibs at the little child flaptable—But because of our semi-Iroquoian French-Canadian accent passe was pronounced PAUSS so I can still hear the lugubrious sound of it and comfort-a-suppers of it, M’ué’n pauss, as you’d expect Bardolph to remember his cockwalloping heigho’s of Eastcheap—My father is in the kitchen, young and primey, shirt-sleeves, chomping up his supper, grease on his chin, bemused, explaining moralities to his angels—They’ll grow 12 feet tall in the grave ere the monstrance that contains the solution to the problem be held up to shine and make true belief to shine, there’s no explaining your way out of the evil of existence—“In any case, eat or be eaten—We eat now, later on the worms eat us.”

Truer words were not spoken from any vantage point on this packet of earth.

“Why? Pourquoi?” cries lil Gerard with his brows forming woe and inabilities—“I dont want it to be like this, me.”

“Though you want or not, it is.”

“I dont care.”

“What you gonna do?”

He pouts; he’ll go to heaven, that’s what; enough of this beastliness and compromising gluttony and compensating muck—Life, another word for mud.

“Come, come, little Gerard, maybe there’s something you know that we dont know”—My father always did concede, Gerard had a deep mind and deep things to think that didnt find nook in insurance policies and printer’s bills—They’d never write Gerard a policy but in eternity, he knew we were here a short while, and pathetic like the mouse, and O patheticker like the cat, and O worse! like the father-cant-explain!

“Awright,” he’ll go to bed and sleep it off, he’ll tuck me in too, and kiss Ti Nin goodnight and the mouse be no lesser for her moment in his hands at noon—Together we pray for the Mouse. “Dear Lord, take care of the little mouse”—“Take care of the cat,” we add to pray, since that’s where the Lord’ll have to do his work.

Ah, and the winds are cold and blow forlorner dust than they’ll ever be able to invent in hell, in Northern Earth here, where people’s hopes though warm fail to conceal the draft, the little draft that works all night moving curtains over radiator heat and sneaks around your blanket, and would bring you outdoors where russet dawn-men with coldchapped ham-hands saw and pound at wood and work and steam with horses and curse the Satan in the air that made all Russias, Siberias, Americas bare to the blasts of infinity.

Gerard and I huddle in the warm gleeful bed of morning, afraid to get out—It’s like remembering before you were born and your hap was at hand and Karma forced you out to start the story.

“Where is she the little mouse now?”

“This morning. The cat has shat her in the woods (Le chat l’a shiez dans l’champ)—with the little pipi yellow you see in the snow down there, see it?”

“Oui.”

“Voilà your fly of last summer, she’s dead too—”

We think it over in motionless trance, as Ma prepares Pa’s breakfast in the fragrant kitchen below.

“Angie,” says Dad at the stove, “that kid’ll break my heart yet—it hurt him so much to lose his little mouse.”

“He’s all heart.”

“With his sickness inside—Ah, it busts my head—Eat or get eaten—not men?—Hah!—There’s a gang downtown would, if their guts were big enough.”

Gerard’s feeling of the holiness of life extended into the realm of romance.

A drunkard under an ample tent was never more adamant concerning how his little sister should behave—“Mama, look what Ti Nin’s doing she’s going to school with her overshoes flopping and throwing her behind around like a flapper!” he yelled one morning looking out the window—It was one of those days when he was suffering a rheumatic fever relapse and had to stay in bed, weeks sometimes, some days worse than others—“Aw look at her!—” He was horrified—He refused to let her do it, when she came home at noon he had a speech worked out for her—“I’m telling you Gerard, you’ll be a priest some day!” my mother’d say.

Meanwhile the kids at church did the sign of the cross some of them with the following words:

“Au nom du père

Ma tante Cafière

Pistalette de bois

Ainsi soit-i”

Meaning

“In the name of the Father

My Aunt Cafière

Pistolet of wood

Amen”

There’s my pa—Emil Alcide Duluoz, at that time, 1925 a hale young printer of 36, dark complexioned, frowning, serious, hardjawed but soft in the gut (tho he had a gut so hard when he oomfed it and dared us kids butt our heads in it or punch fists off it and it felt like punching a powerful basketball)—5:7, Bretonsquat, blue eyed—He had a habit I cant forget, even now I just imitated it, lighting a small fire in the ashtray, out of cigarette pack paper or tobacco wrapping—Sitting in his chair he’d watch the little Nirvana fire consume the paper and render it black crisp void, and understand, mayhap, the bigger kindling of the 3,000 Chillicosms—That which would devour and digest to safety—A little matter of time, for him, for me, for you.

Too, he’d take fresh crisp MacIntosh apples of the Fall and sit in his easy chair and peel em with his pocket knife, making long tassels around and around the fruitglobe so perfect you could have hung them like tassels’ canopies from chandelier to chandelier in the Hall Tolstoy, the which we’d take and sling around and I’d eat em in like great tapeworms and they’d end up flung out in the garbage can like coils of electric wire around and around—After which he’d eat his peeled apple at the gisty whitemeat cutsurface with great slobbering juicy bites that had all the world watering—“Imitate the roar of a lion! Imitate a tiger cat! Imitate an elephant!”—Which he’d do, in his chair, for us, evenings in New England, Gerard on one knee, me on the other, Nin on his lap—That is, when ever there was no poker game to speak of downtown.

“And you my little Gerard, why do you look so pensive tonight? What’s goin on in that little head?” he’d say, hugging his Gerard to him, cheek against soft hair, as Nin and I watched rave lip’t and rapt in the happiness of our childhood, little dreaming what quick work the winds of outside winter would do against the timbers and tendons of his poor house.

In the name of the father, the son, and the Holy Ghost, amen.

Gerard had birds that neighbor and relative could swear did know him personally, they came to his windowsill in the time of his long illnesses, especially Spring, when his rheum-rimmed eyes’d look out on fresh undefiled mornings like captured princesses in must towers—Vile visitations of bile’d turned him green, and white, in the night, his bedpan beneath the bed, but for the birds he had roses for words—“Arrive, mes ti’s anges, Come my little Angels,” and he’d sow his (by Ma prepared) breadcrumbs on the sill and on the short slope roof up there where his sickroom was (a location for a room that forever frets my brain when in gray dreams I dream of houses, that location is always the one that makes me sink, somewhere to the north and west of misery, by peaks, mystery, gables)—Cherry blossom’d May brought him hundreds of gay birds with gloomy beaks that chattered on the roof around his crumbs—But he’d cry: “Why dont the little birds come to me?! Dont they know I wont hurt them?”

“Of course they dont, they cant know—for all they know you’re a boy, and boys hurt birds.”

“And birds hurt boys?”

“And birds never hurt a boy, but the b

oy will stone his dozen and upset the nests of a dozen fledgelings in his nasty prime.”

“Why? Why is everyone so mean? Didnt God see to it that we—of all people—people—would be kind—to each other, to animals.”

God made no provisions for that winter.

The birds chatter, come come close at hand, he glees and jumps up and down at his pillow: “That one’s coming, that one I’m tellin you, he’ll end up in my hand!”

“I hope,” my mother’d say with wise eyes and unwisely in the night pray for it and worthily praise him—My father couldnt believe it.

“Ah, if I could buy him birds!”

“Just one little bird, just ONE,” he’d cry, as I sat in my little chair by the bed watching, fingering the crumb pan with little pudgy fingers so fat they called me Ti Pousse, Little Thumb.

“Come here, Little Thumb, look, the little grey bird, doesnt he look like he wants to eat in my hand and give me a little kiss?”

“Yes.”

“Wouldnt you like to kiss that little thing?”

“Yes.”

“Yes yes little bird come on.”

But a chance noise of breadtruck drives the whole flock away kavroom, for the next tree, where they jabber the new news—Tears come to Gerard’s eyes, his lips form a fateful pout, a groan comes, it means “Ah what’s the use—if I loved them any more they’d have honey and balm for breakfast and have beaks of gold, yet they avoid me like a rat dripping bacteria—like a falcon—like a man.”

“Gerard,” my mother’d explain, “dont make yourself sad about the little birds. Do you know why? Because God sees and knows you love them and he’ll reward you.”

“In heaven I’ll have all the birds I want.”

“Yes in heaven—and maybe on earth, have courage, patience.”

With his little belly he heaves a heigh ho sigh, ‘t’would be a good thing to be in that snowy somewhere and rosy nowhere where patience is just a word and no bellies burdenly pain. “Yes, in heaven there are birds, millions of birds, even smaller than these, big like butterflies, smaller, like ants, white like an angel—everywhere.” He’d turn to his drawing board propped on his lap and start drawing his dreary eternities and dreams of paradise. He was an amazing artist at the age of 8. He drew pictures that my old man actually disbelieved as his own when he saw them a-nights:

“Gerard did that?—look here!”

Ditto my father’s friends—To prove it he’d draw right in front of them, boats sailing on the blue ocean (copied from the Saturday Evening Post), birds, bridges, lambies, people’s hats—Also he had an erector set and built up impossible engineering marvels like vast complicated ferris wheels and race cars and the usual tote-cranes and trucks that were borrowed from the book of instructions—Heaving the book aside he’d of a sick morning (as I watch) whip up beautiful little baby carriages or baby cribs for Nin to put her dolls in at noon, all set with little draperies—I wonder if she still remembers these latter days as she stares at Television’s rancid blight whole evenings in her home parlor, waiting to join him in Heaven—

For me he’d concoct delights at the drop of my saying it, “Make me a ritontu,” which is I dont know what, and he’d make a crazy construction and I’d play with it and try to unscrew it and chew the edges of it—

Then the birds would come flocking and singin in rollicking nations around our holy roof again, and he’d call for bread, and multiply it in crumbs, and sow it to the sisters who pecked and picked—

“Vien, vien, vien,” the picture of him hand outstretched and helpless in bed calling at the open window for the celestial visitors, enough to make my heart leap from a cold indifferent lair (of late)—

He never got his hand on a bird, naturally, and what transformation might have taken place in such a case I do not know—

Meanwhile Dr. Simpkins came and went with his oldfashioned satchel and his listen-tubes and pipes and pills and pumps and surprised us all by his gravity and inability to speak—He had no long hope for the life of Gerard.

I didnt understand anything that was going on, I was rosy plump Little Thumb Ti Pousse glad to be in the same world as Gerard.

One night we’re on the kitchen floor with the Boston American, I remember distinctly the pinksheet Hearst evening news, on the front page is the photo of a woman who’s murdered someone, I take my scissors and stab her right in the eye impaling the paper on the linoleum—“Non non Ti Jean never do that!” Didnt understand (as I remember myself) the glee, the mindless happy glee that went into that vigorous stab—But to Gerard the mindlessness was precisely the horror and the currency of a hateful hopeless world—“Non, non, never do anything like that,—Ah poor Ti Pousse, you dont understand—Look, take out the scissors, fix her eyes”—We smooth the ruffled paper, stroke the paper lady’s eyes, brood over our sin, rectify hells, fruition good Karmas for ourselves, repent, go to confession—His lips tsk tsk and pout—Kissable Gerard, to kiss him and that pout of pain must have been as soft a sin as kissing a lamb in the belly or an angel in her wing—He gave me piggybacks to prove that other pastimes were better and that I was forgiven—He even let me “beat him up” in mock fights where we rolled on the linoleum and I screamed—

With my little hands clasped behind me I stand at the kitchen window, sometime not long after, on a gray blizzard day, watching the inky snowflakes descend from infinity and hit the ground where they become miraculous white, whereby I understand why Gerard was so white and because of man came of such black sources—It was by virtue of his pain-on-earth, that his black was turned to white.

It’s a cold crisp morning in October, Gerard is going to school with his books and bread and butter and banana lunch and an apple—I watch him going down Beaulieu Street, alone—Gangs of kids run around—At the end of Beaulieu Street is the large gravel play yard of the Green Public School where because the kids werent Catholics the nuns have been telling Gerard and Nin and the kids of St. Louis de France Parochial School that they have tails concealed beneath their trousers—Which some of us (I for one) seriously believe—At that street Gerard turns right to go to St. Louis which is right there along three wooden fences of bungalows, first you see the nun’s home, redbrick and bright in the morning sun, then the gloomy edifice of the schoolhouse itself with its longplank sorrow-halls and vast basement of urinals and echo calls and beyond the yard, with its special (I never forgot) little inner yard of cinder gravel separated from the big dirt yard (which becomes a field down at Farmer Kenny’s meadow) by a small granite wall not a foot high, that everyone sits on or throw cards against—The big game is card slinging, the bubblegum cards with pictures of movie stars and baseball players (Great God! it musta been Vilma Banky and Rogers Hornsby with young faces on the fragrant bubblegum cards)—They are flung against the wall, nearest wins—The big game at recess—Gerard comes slowly ruminating in the bright morn among the happy children—Today his mind is perplexed and he looks up into the perfect cloudless empty blue and wonders what all the bruiting and furor is below, what all the yelling, the buildings, the humanity, the concern—“Maybe there’s nothing at all,” he divines in his lucid pureness—“Just like the smoke that comes out of Papa’s pipe”—“The pictures that the smoke makes”—“All I gotta do is close my eyes and it all goes away”—“There is no Mama, no Ti Jean, no Ti Nin, Papa—no me—no kitigi” (the cat)—“There is no earth—look at the perfect sky, it says nothing”—Little snivelly Plourdes is losing at a game of cards in the corner, the bullies buffet him out—“He’s crying—he only thinks of his luck and his luck is worse”—“his luck is mixed up in the bad and the poor”—“Ah the world”—To the other end is the Presbytère (Rectory) where Father Pere Lalumière the Curé lives, and other priests, a yellow brick house awesome to the children as it is a kind of chalice in itself and we imagine candle parades in there at night and snow white lace at breakfast—Then the

church, St. Louis de France, a basement affair then, with concrete cross, and inside the ancient smooth pews and stained windows and stations of the cross and altar and special altars for Mary and Joseph and antique mahogany confessionals with winey drapes and ornate peep doors—And vast solemn marble basins in which the old holy water lies, dipped by a thousand hands—And secret alcoves, and upper organs, and sacrosanct backrooms where altar boys emerge in lace and blacks and the priests march forth bearing kingly ornaments—Where Gerard had been and kept on going many a time, he liked to go to church—It was where God had his due—“When I get to Heaven the first thing I’m gonna ask God is for a beautiful little white lamb to pull my wagon—Ai, I’d like to be there right away already, not have to wait—” He sighs among the birds and kids, and over at the end of the yard are gathered the teacher nuns getting ready for the morning bell and lineup, the morning breeze moving their black robes and pendant black rosaries slightly, their faces pale around rheumy eyes, delicate as lacework their features, distant as chalices, rare as snow, untouchable as holy bread of the host, the mothers of thought—Striking awe in children—Monastic ladies devoted to sewing and devout service in their gloomy redbrick hermitage there where we saw them in the windows with their cap flares and cameo profiles bent over rosaries or missals or embroideries, they themselves mostly all the time vigorously curiously digging the scene outdoors—In fact right now a hobo from Louisiana and the East Texas Oil fields who happens to be passing thru Lowell, lies in the straw grass below the Green School fence, knee on knee, grass in mouth, contemplating the flawless void and humming the blues and what could be the thoughts of the old nun at the window watching him—“Lazy bum! (Paresseux!)”—“Robber!—Sinner!”

Typical of Gerard that he doesnt look to the fields, the trees down further where Farmer Kenny’s fields become a thicket and after a few cottages of Centerville spurting morning smoke the distant hills and horizon meadows of on-to-Dracut and New Hampshire and all that pale brown promise of the sere continent—Gerard was inward turned like a chalice of gold bearing a single holy host, bounden to his glory doom—He sits on the little wall contemplating the kids, and the bum in the field, the nuns in the window, the little girls hopskotching beyond and where Ti Nin is screaming with the rest—“Little crazy, look at her gettin all excited—she doesnt understand the blue sky this morning, she doesnt care like a little kitty—But look—” he looks up, mouth agape—“There’s nothing there, not a cloud, not a sound—just like it was water upside-down and what’s the bugs down here?” The air is crisp and good, he breathes it in—The bell rings and all the scufflers go to shuffle in the dreary lines of class by class with the head nun overlooking all, the parade ground formation of the new day, latecomers running thru the yard with flying books—A dog barking, and the coughs, and the gritty gravel under restless many little shoes—Another day of school—But Gerard has eyes up to sky and knows he’ll never learn in school what he’d like to learn this morning from that sky of silent mystery, that heartbreaking sayless blank that wont tell men and boys what’s up—“It’s the eye of God, there’s no bottom—”

Tristessa

Tristessa On the Road

On the Road The Dharma Bums

The Dharma Bums Maggie Cassidy

Maggie Cassidy Big Sur

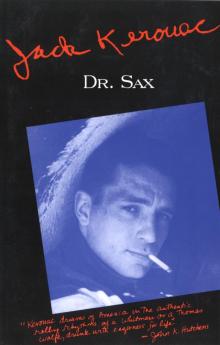

Big Sur Dr. Sax

Dr. Sax Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46

Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46 The Sea Is My Brother

The Sea Is My Brother The Town and the City: A Novel

The Town and the City: A Novel Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Desolation Angels: A Novel

Desolation Angels: A Novel Book of Sketches

Book of Sketches Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha

Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha The Electrocution of Block 38383939383

The Electrocution of Block 38383939383 Haunted Life

Haunted Life Visions of Gerard

Visions of Gerard Orpheus Emerged

Orpheus Emerged Book of Blues

Book of Blues The Subterraneans

The Subterraneans The Haunted Life

The Haunted Life The Unknown Kerouac

The Unknown Kerouac The Town and the City

The Town and the City Visions of Cody

Visions of Cody Atop an Underwood

Atop an Underwood Lonesome Traveler

Lonesome Traveler Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg Vanity of Duluoz

Vanity of Duluoz Desolation Angels

Desolation Angels On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition)

On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition) The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel

The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel Wake Up

Wake Up The Poetry of Jack Kerouac

The Poetry of Jack Kerouac Doctor Sax

Doctor Sax