- Home

- Jack Kerouac

Visions of Gerard Page 3

Visions of Gerard Read online

Page 3

“Gerard Duluoz, you’re not in line—!”

“Yes, Sister Marie.”

“Silence! The Mother Supérieure is going to talk!”

“Ssst! Mercier! Give me my card!”

“It’s mine!”

“It is not!”

“Shut your trap! (Famme ta guêle).”

“I’ll fix you.”

“Prrrrt”

“Silence!”

Silence over all, the rustle of the wind, the banners of two hundred hearts are still—Under that liquid everpresent impossible-to-understand undefiled blue—

A few Fall trees reach faint red twigs to it, smoke-smells wraith to twist like ghosts in noses of morning, the saw of Boisvert Lumberyard is heard to whine at a log and whop it, the rumble of the junkmen’s cart on Beaulieu Street, one little kid cry far off—Souls, souls, the sky receives it all—Nobody can comment on the only reality which is Crystal Naught not even Viking Press—Not even Père Lalumière who now with clothesline-fresh garments parades downhall in the Presbytère whistling to his room, lacrimae rerum of the world in his smarting morning eyes, pettling and purtling with his lips at thought of the good cortons pork-scraps for breakfast comin up just now soon’s he gets his dud-o’s on and sweeps officially to another day as Curé of the World—A good man and true, like Our Mayor in his City Hall and the President Coolidge at his desk 500 miles South to the morning that brights the Potomac same as brights the Merrimac of Lowell—In other words, and who will be the human being who will ever be able to deliver the world from its idea of itself that it actually exists in this crystal ball of mind?—One meek little Gerard with his childly ponderings shall certainly come closer than Caesarian bust-provokers with quills and signatures and cabinets and vestal dreary laceries—I say.

O, to be there on that morning, and actually see my Gerard waiting in line with all the other little black pants and the little girls in their own lines all in black dresses trimmed with white collars, the cuteness and sweetness and dearness of that oldfashion’d scene, the poor complaining nuns doing what they think is best, within the Church, all within Her Folding Wing—Dove’s the church—I’ll never malign that church that gave Gerard a blessed baptism, nor the hand that waved over his grave and officially dedicated it—Dedicated it back to what it is, bright celestial snow not mud—Proved him what he is, ethereal angel not Festerer—The nuns had a habit of whacking the kids on the knuckles with the edge part of the ruler when they didnt remember 6 X 7, and there were tears and cries and calamities in every classroom every day—And all the usual—But it was all secondary, it was all for the bosom of the Grave Church, which we all know was Pure Gold, Pure Light.

That bright understanding that lights up the mind of the soldier who decides to fight to death—“O Arjuna, fight!”—That’s what’s implied at the rail of the altar of repentance, for the repenter gives up self and admits he was a fool and can only be a fool and may his bones dissolve in the light of forever—All my sins, leaving not jot or tittle out, even unto the smallest least-noticeable almost-not-sin that you could have got away with with another interpretation—But you bumbling fool you’re a mass of sin, a veritable barrel of it, you swish and swash in it like molasses—You ooze mistakes thru your frail crevasses—You’ve bungled every opportunity to bless somebody’s brow—You had the time, you will have the time, you’ll yawn and wont understand—Ah you’re a bum as you are—’T were better to dissolve you—The Holy Milk you act like a curdler and a bacteria in it, yellow scum, sometimes purple or pot green—As you are, it wont do—The Lord knows he made a mistake—We talk about “the Lord” out of the corner of our hands for want of a better way to describe the undefilable emptiness of the blue sky on such mornings as the morning Gerard wondered—It’s typical of us to compromise and anthropomorphalize and He it, thus attributing to that bright perfection of Heaven our own low state of selfbeing and selfhood and selfconsciousness and selfness general—The Lord is no-body—The Lord is no bandyer with forms—All conditional and talk, what I have to say, to point it out—Miserable as a dull sermon on a dull rainy morning in a damp church in the North, and Sunday to boot—We are baptized in water for no unsanitary reason, that is to say, a well-needed bath is implied—Praise a woman’s legs, her golden thighs only produce black nights of death, face it—Sin is sin and there’s no erasing it—We are spiders. We sting one another.

No man exempt from sin any more than he can avoid a trip to the toilet.

Gerard and all the boys did special novenas at certain seasons and went to confession on Friday afternoon, to prepare for Sunday morning when the church hoped to infuse them with some of the perfection embodied and implied in the concept of Christ the Lord—Even Gerard was a sinner.

I can see him entering the church at 4 PM, later than the others due to some errand and circumstance, most of the other boys are thru and leaving the church with that lightfooted way indicative of the weight taken off their minds and left in the confessional—The redemption gained at the altar rail with penalty prayers, doled out according to their lights and darknesses—Gerard doffs his cap, trails fingertip in the font, does the sign of the cross absently, walks half-tiptoe around to the side aisle and down under the crucified tablets that always wrenched at his heart when he saw them (“Pauvre Jésus, Poor Jesus”) as tho Jesus had been his close friend and brother done wrong indeed—He genuflects and enters the pew and puts little knees to plank, the plank is worn and dusted with a million kneeings morning noon and night—He starts a preliminary prayer—“Hail Mary—” in French the prayer: “Je vous salue Marie pleine de grâce”—Grace and grease interlardedly mixed, since the kids didnt say “grace,” they said “grawse” and no power on earth could stop them—The Holy Grease, and good enough—“Le Seigneur est avec vous—vous êtes bénie entre toutes les femmes”—Blessed among and above all women, and they saw their mother’s and sister’s eyes as one pair of eyes—“Et Jésus le fruit de vos entrailles”—“entrailles” the powerful French word for Womb, entrails, none of us had any idea what it meant, some strange interior secret of Mary and Womanhood, little dreaming the whole universe was one great Womb—The coil of that thought and wording, not conducive to a true understanding of the nature and emptiness-aspect of Wombhood, the perfect blue sky’s our Womb (but not our guts and coils)—“Sainte Marie, Mère de Dieu, priez pour nous, pécheurs, maintenant et à l’heure de notre mort”—No comma in the minds and thoughts of the little boys (and their fathers) who ran it straight thru “pécheurs maintenant et à l’heure de notre mort”, sinner always right unto death, no help no hope, born—

“Ainsi soit-il”, amen, none of them knowing either what that meant, “thus it is,” it is what is and that’s all it is—thinking ainsi soit-il to be some mystic priestly secret word invoked at altar—The innocence and yet intrinsic purity-understanding with which the Hail Mary was done, as Gerard, now knelt in his secure pew, prepares to visit the priest in his ambuscade and palace hut with the drapes that keep swishing aside as repentent in-and-out sinners come-and-go burdened and disemburdened as the case may be and is, amen—

Now Gerard ponders his sins, the candles flicker and testify to it—Dogs burlying in the distance fields sound like casual voices in the waxy smoke nave, making Gerard turn to see—But in and throughout all a giant silence reigns, shhhhhing, throughout the church like loud remindful ever-continuing abjuration to stay be straight and honest with your thought—

“I pushed lil Carrufel”—It took place in the schoolyard, with throw-cards Gerard had contrived a card-castle at midday recess, the first grader knocked it down coming too close and curious, without reflection Gerard raged and pushed him, really mad, “Look what you done to my house—Nut!” then instantly repented and too late—Now he pouts to concede: “But it was my house—mautadit fou” (a form of dyazam fool, or, drazyam, or whichever, used by children and in fact everyone including prelate

s, congressmen and druggists)—“But when I pushed him he turned pale, he didn’t know anybody was gonna push him at that moment and that was the moment that hurt him—Ya venu blême comme une vesse de carême (He got pale as a lenten fart)—His heart sank, and it’s me that done it—It’s a clear sin—My Jesus wouldnt have liked that watching from his cross”—He turns eyes up and around to the cross, where, with arms extended and hands nailed, Jesus sags to his foot-rest and bemoans the scene forever, and always it strikes in Gerard’s naturally pitiful heart the thought “But why did they do that?”—Looking there at the foolish mistakes of past multitudes, plain as day to see, right on the wall—The massive silence enveloping the graceful gentle form of hip and loincloth, limbs and knees, and the tortured thin breast—And the unforgettable downcast face—“God said to his son, we’ve got to do this—they decided in Heaven—and they did it—it happened—INRI!”—“INRI—that means, it happened!—or else, INRI, the funny ribbon on the cross of the lover they killed—and, they put a nail through it”—Whatever mysterious thoughts that lie beneath in the bent heads of people and children in churches and temples century after century—“He’s crying!” moaned Gerard, seeing it all.

Two other sins to confess: the deep sin of looking at Lajoie’s and Lajoie could look at his, at the urinals, Wednesday morning, in the corner, for a long time—On purpose—Gerard blushes to think of it—He sees the strange image of Lajoie’s, different, curlier than his, he twinges to urinate namelessly and twists in his knee rest with the horror of his shame, not knowing—Sin’s so deeply ingrained in us we invent them where they aint and ignore them where they are—Across his mind sneaks the proposition to avoid referring to the priest—But God will know—And to mock the kindly ear of the listener Priest, who expects what there is, by removing one whit, a human sin divine to discover—“Poor Father Priest, what’ll he know if I dont tell him? he wont know anything and he’ll comfort me and send me off with my prayer, well it’ll be a big sin to hide him a sin—like if I’d spit in his eyes when he’s dead, like”—

The fortunate priest, Père Anselme Fournier, of Trois Rivières Quebec, the last of twelve sons but the first in his father’s eye, pink-handed where he might have been horny-handed from the soil of Abraham, receives Ti Gerard in the confessional by sliding open his panel and bending quick ear obedient and loaded with long afternoon—Coughs revolve around the ceiling and sail and set in the pew sea, a knee-rest scrapes Sca-ra-at! with a harsh harmonizing bang from the altar where a worker creaks around with chair and candle snuffer—

“Bénit” is the only word, “bless,” Gerard hears as the priest quickly mutters the introductory invocation and then his ear is ready—Gerard can faintly smell the adult breath and that peculiar adult smell of old teeth in old mouths long at work—“Bz bz bz” he hears as his predecessor in the confessional, just let out, prays fast and furious his repentant penalty rosaries at the rear seat half on his way to run out and slap cap on and run screaming across dusk stained fields of stubble and raw mud, to gangs in clover dales wrangling with rocks—A bird zings across the reddening late sky and over the roof of St. Louis de France, as though the Holy Ghost wanted it—Saffron is the east, white is the west, where a bank cloud hides the thrower Sun, but soon it’ll all girdle and engolden and be rich red gambling sunset splendor, again, as yesterday—No school tomorrow is the frost announcement in the field grass, in the quiet corners of the schoolyards—Gerard senses all this but his day’s work is just begun.

“My father, I confess that I pushed a little boy because he made me mad.”

“Did you hurt him?”

“No—but I hurt his heart.”

The priest is amazed to hear the refinement of it, the hairsplitting elegant point of it, (“He’ll make a priest” he inner grins).

“Yes, you’re right, my child, it hurt his heart. Why did you push him?” he pursues in conclusion with that sorrowful tender sorriness of the priest in the confessional as tho and as much to say “When all is said and done, why do we sit here and have to admit the sinningness of man.”

“I pushed him because he had broken my little card-house.”

“Ah.”

“It made me mad.”

“You flew into a rage.”

“Oui.”

“You didnt think—He was younger than you.”

“Oui, just a little boy of the first grade.”

“Aw,”—regretfully the fine priest looks around at Gerard briefly, commisserating as tender heart to tender heart—Ah, a scene going on in the little church of dusk! And somewhere wars!

“Well,” to conclude, “you know your sin—You’ll have to keep your patience the next time—Keep well your idea, that you hurt his heart if not his body”—admiringly—“you’ve understood it yourself. I am certain,” he takes trouble to add in spite of an overburdened afternoon of work in there, “that the Lord understands you.—And, there is something else you want to tell me.”

“Yes my father”—and this Gerard says feeling like a beast piling animality on animality,—“I—er—” he stammers, confuses, and blushes, and stops.

“I’m waiting, my little boy.”

Quickly Gerard whispers him the news about the urinal, Saturday Afternoon Confessions in St. All’s had never heard a lurider admission it would seem from the stealth of his ps-ps’es.

“Ah, and did you touch his little dingdong?” (Sa tite gidigne).

Gerard: “Aw non!” glad he has a loophole and all because he never thought of it, mayhap—

“Well,” sighing, “I have confidence in you my child that you’ll never do it again. And something else? anything else?”

Gerard instantly remembers still another sin, forgotten until then—“I told the Sister I had studied my Catechism, and no I hadnt studied it.”

“And you didnt know it?”

“Yes I knew it, but from another time, I remembered.”

(“Ah, that’s no sin,” thinks the Priest) and closes up accounts with: “Very well, that’s all? Well then, say your rosary and fifteen Hail Mary’s.”

“Yes my father.”

The gracious slide door slides, Gerard is facing the good happy wood, he runs out and hurries lightfoot to the altar, fit to sing—

It’s all over! It was nothing! He’s pure again!

He prays and bathes in prayers of gratitude at the white rail near the blood red carpet that runs to the stainless altar of white-and-gold, he clasps little hands over leaned elbows with hallelujahs in his eyes—To be God, and to’ve seen his eyes, looking up at my altar, with that beholding bliss, all because of some easy remission of mine, were hells of guilt I’d say—But God is merciful and God above all is kind, and kind is kind, and kindness is all, and it all works out that the mortal angel at the altar rail as the church hour roars with empty silence (everybody gone now, including the last priest, Gerard’s priest) is bathed in blisskindness whether it would be pointed out or not that other easier ways might do the job as well, which may be doubtful, snow being snow, divinity divinity, holiness holiness, believing believing.

All alone at the rail he suddenly becomes conscious of the intense roaring of the silence, it fills his every ear and seems to permeate throughout the marble and the flowers and the darkening flickering air with the same pure hush transparency—The heaven heard sound for sure, hard as a diamond, empty as a diamond, bright as a diamond—Like unceasing compassion its continual near-at-hand sea-wash and solace, some subtle solace intended to teach some subtler reward than the one we’ve printed and that for which the architects raised.

Enveloped in peaceful joy, my little brother hurries out the empty church and goes running and skampering home to supper thru raw marched streets.

“Did you go to your confession, Lil Gerard?”

“Oui.”

“Come eat, my golden angel, m

y pitou, my lil Mama’s cabbage.”

I’m sitting stupidly at a bed-end in a dark room realizing my Gerard is home, my mouth’s been open in awe an hour you might think the way it’s sorta slobbered and run down my cheeks, I look down to discover my hands upturned and loose on my knees, the utter disjointed inexistence of my bliss.

Me too I’d been hearing the silence, and seeing swarms of little lights thru objects and rooms and walls of rooms.

None of the elements of this dream can be separated from any other part, it is all one pure suchness.

Would I were divinest punner and tell how the cold winds blow with one stroke of my quick head in this harsh unhospitable hospital called the earth, where “thou owest God a death”—Time for me to get on my own horse—

Tristessa

Tristessa On the Road

On the Road The Dharma Bums

The Dharma Bums Maggie Cassidy

Maggie Cassidy Big Sur

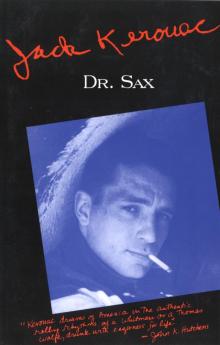

Big Sur Dr. Sax

Dr. Sax Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46

Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46 The Sea Is My Brother

The Sea Is My Brother The Town and the City: A Novel

The Town and the City: A Novel Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Desolation Angels: A Novel

Desolation Angels: A Novel Book of Sketches

Book of Sketches Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha

Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha The Electrocution of Block 38383939383

The Electrocution of Block 38383939383 Haunted Life

Haunted Life Visions of Gerard

Visions of Gerard Orpheus Emerged

Orpheus Emerged Book of Blues

Book of Blues The Subterraneans

The Subterraneans The Haunted Life

The Haunted Life The Unknown Kerouac

The Unknown Kerouac The Town and the City

The Town and the City Visions of Cody

Visions of Cody Atop an Underwood

Atop an Underwood Lonesome Traveler

Lonesome Traveler Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg Vanity of Duluoz

Vanity of Duluoz Desolation Angels

Desolation Angels On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition)

On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition) The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel

The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel Wake Up

Wake Up The Poetry of Jack Kerouac

The Poetry of Jack Kerouac Doctor Sax

Doctor Sax