- Home

- Jack Kerouac

Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46 Page 7

Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46 Read online

Page 7

But I loved Dean Hawkes, everybody did, he was an old, short bespectacled old fud with glee in his eyes. Him and his egg. . .

VI

The opening game of the season the freshman team traveled to New Brunswick NJ for a game against Rutgers’ freshmen. This was Saturday Oct 12, 1940, and as our varsity defeated Dartmouth 20–6, we went down there and I sat on the bench and we lost 18–7. The little daily paper of the college said: FRESHMEN DROP GRID OPENER TO RUTGERS YEARLINGS BY 18–7 COUNT. It doesnt mention that I only got in the game in the second half, just like at Lowell High, and the article concludes with: ‘The Morningsiders showed a fairly good running attack at times with Jack Duluoz showing up well . . . Outstanding in the backfield for the Columbia Frosh were Marsden [police chief’s son], Runstedt and Duluoz, who was probably the best back on the field.’

So that in the following game, against St Benedict’s Prep, okay, now they started me.

But you remember what I boasted about how, to beat St John’s, you gotta have old St John on the team. Well I have a medal, as you know, over my backyard door. It’s the medal of St Benedict. An Irish girl once told me: ‘Whenever you move into a new house two things you must do according to your blood as an ancient Gael: you buy a new broom, and you pins a St Benedict medal over the kitchen door.’ That’s not the reason why I’ve got that medal now but here’s what happened:

After the Rutgers game, and Coach Libble’d heard about my running, and now his backfield coach Cliff Battles was interested, everybody came down to Baker Field to see the new nut run. Cliff Battles was one of the greatest football players who ever lived, in a class with Red Grange and the others, one of the greatest runners anyway. I remember as a kid, when I was nine, Pa saying suddenly one Sunday ‘Come on Angie, Ti Nin, Ti Jean, let’s all get in the car and drive down to Boston and watch the Boston Redskins play pro football, the great Cliff Battles is running today.’ Because of traffic we never made it, or we were waylaid by ice cream and apples in Chelmsford, Dunstable or someplace and wound up in New Hampshire visiting Grandmère Jean. And in those days I kept elaborate clippings of all sports and pasted them carefully among my own sports writings, in my notebooks, and I knew very well about Cliff Battles. Now here all of a sudden the night before the game with St Benedict and we freshmen are practicing, here comes Cliff Battles and up to me and says ‘So you’re the great Dulouse that ran so good at Rutgers. Let’s see how fast you can go.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘I’ll race you to the showers; practice is over.’ He stood there, 6 foot 3, smiling, in his coach pants and cleated shoes and sweat jacket.

‘Okay,’ says I and I take off like a little bird. By God I’ve got him by 5 yards as we head for the sidelines at the end of the field, but here he comes with his long antelope legs behind me and just passes me under the goalposts and goes ahead 5 yards and stops at the shower door, arms akimbo, saying:

‘Well cant you run?’

‘Ah heck your legs are longer than mine.’

‘You’ll do allright kid,’ he says, pats me, and goes off laughing. ‘See you tomorrow,’ he throws back.

This made me happier than anything that had happened so far at Columbia, because also I certainly wasnt happy that I hadnt yet read the Iliad or the Odyssey, John Stuart Mill, Aeschylus, Plato, Horace and everything else they were throwing at us with the dishes.

VII

Comes the St Benedict game, and what a big bunch of lugs you never saw, they reminded me of that awful Blair team a year ago, and the Malden team in high school, big, mean-looking, with grease under their eyes to shield the glare of the sun, wearing mean-looking brown-red uniforms against our sort of silly-looking (if you ask me) light-blue uniforms with dark-blue numerals. (‘Sans Souci’ is the name of the Columbia alma mater song, means ‘without care’ humph.) (And the football rallying song is ‘Roar Lion Roar’, sounds more like it.) Here we go, lined up on the field, on the sidelines I see the Coach Lu Libble is finally there to give me the personal once-over. He’s heard about the Rutgers game naturally, and he’s got to think of next year’s backfield. He’d heard, I s’pose, that I was a kind of nutty French kid from Massachusetts with no particular football savvy like his great Italian favorites from Manhattan that were now starring on the varsity (Lu Libble’s real name is Guido Pistola, he’s from Massachusetts).

St Benedict was to kick off. They lined up, I went deep into safety near the goal line as ordered, and said to myself ‘Screw, I’m going to show these bums how a French boy from Lowell runs, Cliff Battles and the whole bunch, and who’s that old bum standing next to him? Hey Runstedt, who’s that guy in the coat next to Cliff Battles there near the water can?’

‘They tell me that’s the coach of Army, Earl Blaik, he’s just whiling away an afternoon.’

Whistle blows and St Benedict kicks off. The ball comes wobbling over and over in the air into my arms. I got it secure and head straight down the field in the direction an arrow takes, no dodging, no looking, no head down either but just straight ahead at everybody. They’re all converging there in midfield in smashing blocks and pushings so they can get through one way or the other. A few of the red Benedicts get through and are coming straight at me from three angles but the angles are narrow because I’ve made sure of that by coming in straight as an arrow down the very middle of the field. So that by the time I reach midfield where I’m going to be clobbered and smothered by eleven giants I give them no look at all, still, but head right into them: they gather up arms to smother me: it’s psychological. They never dream I’m really roosting up in my head the plan to suddenly (as I do) dart, or jack off, bang to the right, leaving them all there bumbling for air. I run as fast as I can, which I could do very well with a heavy football uniform, as I say, because of thick legs, and had trackman speed, and before you know it I’m down the sidelines all alone with the whole twenty-one other guys of the ball game all befuddling around in midfield and turning to follow me. I hear whoops from the sidelines. I go and I go. I’m down to the 30, the 20 and 10, I hear huffing and puffing behind me, I look behind me and there’s that selfsame old longlegged end catchin up on me, like Cliff Battles done, like the guy last year, like the guy in the Nashua game, and by the time I’m over the 5 he lays a big hand on the scruff of my neck and lays me down on the ground. A 90-yard runback.

I see Lu Libble and Cliff Battles, and Rolfe Firney our coach too, rubbing their hands with zeal and dancing little Hitler dances on the sidelines. But St John aint got a chance against St Benedict, it appears, because anyway naturally by now I’m out of breath and that dopey quarterback wants me to make my own touchdown. I just cant make it. I want to controvert his order, but you’re not supposed to. I puff into the line and get buried on the 5. Then he, Runstedt, tries it, and the big St Ben’s line buries him, and then we miss the last down too and are down on the 3 and have to fall back for the St Benedict punt.

By now I’ve got my wind again and I’m ready for another go. But the punt that’s sent to me is so high, spirally, perfect, I see it’s going to take an hour for it to fall down in my arms and I should really raise my arm for a fair catch and touch it down to the ground and start our team from there. But no, vain Jack, even tho I hear the huffing and puffing of the two downfield men practically say ‘Ally Oop’ as I feel their four big hands squeeze like vises around my ankles, two on each, and puffing with pride I do the complete vicious twist of my whole body so that I can undo their grip and move on. But their St Benedict grips have me rooted to where I am as if I was a tree, or an iron pole stuck to the ground, I do the complete turnaround twist and hear a loud crack and it’s my leg breaking. They let me fall back deposited gently on the turf and look at me and say to each other ‘The only way to get him, dont miss’ (more or less).

I’m helped off the field limping.

I go into the showers and undress and the trainer massages my right ca

lf and says ‘O a little sprain wont hurt you, next week it’s Princeton and we’ll give them the old one-two again Jacky boy.’

VIII

But, wifey, it was a broken leg, a cracked tibia, like if you cracked a bone about the size of a pencil and the pencil was still stuck together for that hairline crack, meaning if you wanted you could just break the pencil in half with a twist of two fingers. But nobody knew this. That entire week they told me I was a softy and to get going and run around and stop limping. They had liniments, this and that, I tried to run, I ran and practiced and ran but the limp got worse. Finally they sent me off to Columbia Medical Center, took X rays, and found out I had broken my tibia in right leg and that I had been spending a week running on a broken leg.

I’m not bitter about that, wifey, so much as that it was Coach Lu Libble who kept insisting I was putting it on and told the freshman coaches not to listen to my ‘lamentings’ and make me ‘run it off’. You just can’t run off a broken leg. I saw right then that Lu for some reason I’ll never understand had some kind of bug against me. He was always hinting I was a no-good and with those big legs he ought to put me in the line and make ‘a watch charm guard’ out of me.

Yet (I guess I know now why) it was only that summer, I forgot to mention, Francis Fahey had me come out to Boston College field to give me a tryout for once and for all. He said ‘You really must come to BC, we’ve got a system here, the Notre Dame system, where we take a back like you and with a good line play spring him loose down the field. Over at Columbia with Lu Libble they’ll have you come around from the wing, you’ll have to run a good twenty yards before you get back to the line of scrimmage with that silly KT-79 reverse type play of his and you’ll only at best manage to evade maybe the end but the secondary’ll be up on yours in no time. With us, it’s boom, right through tackle, guard, or right or left end sweep.’ Then Fahey’d had me put on a uniform, got his backfield coach MacLuhan and said: ‘Find out about him.’ Alone in the field with Mac, facing him, Mac held the ball and said:

‘Now, Jack, I’m going to throw this ball at you in the way a center does; when you get it you’re off like a halfback on any kinda run you wanta try. If I touch you you’re out, so to speak, and you know darn well I’m going to touch you because I used to be one of the fastest backs in the east.’

‘Phooey you are,’ I thought, and said ‘Okay, throw it.’ He centered it to me, direct, facing me, and I took off out of his sight, he had to turn his head to watch me pass around his left, and that’s no Harvard lie.

‘Well,’ he conceded, ‘you’re not faster than I am but by God where’d you get that sudden takeoff? Track?’

‘Yep.’ So in the showers of BC afterward, I’m wiping up, I hear Fahey and Mac discussing me in the coaches’ showers and I hear Mac say to Fahey:

‘Fran, that’s the best halfback I ever saw. You’ve got to get him to BC.’

But I went to Columbia because I wanted to dig New York and become a big journalist in the big city beat. But what right had Lu Libble to say I was a no-good runner. And, wifey, listen to this, what about the night the winter before, at HM, when Francis Fahey had me meet him on Times Square and took me to William Saroyan’s play My Heart’s in the Highlands, and in the intermission when we went down to the toilet I’m sure I saw Rolfe Firney the Columbia man watching from behind the crowd of men? On top of which they then sent Joe Callahan to New York to take me out on the town too, to further persuade me about Boston College, and eventually Notre Dame, but here I was in Columbia, Pa had lost his job, and the coach thought I was so no-good he didnt even believe I’d broken my leg in earnest.

Years later I published a poem about this on the sports page of Newsday, the Long Island newspaper: fits pretty good: because it also involves the later fight my father had with Lu about his not playing me enough and some arrangement that went sour whereby Lu was s’posed to help him get a linotypist job in New York and nothing came of it:

TO LU LIBBLE

Lu, my father thought you put him down

and said he didnt like you

He thought he was too shabby for your

office; his coat had got so

And his hair he’d comb and come

into an employment office with me

And have me speak alone with the man

for the two of us, then sigh

And repented we home, to Lowell; where

sweet mother put out the pie

anywye.

In my first game I ran like mad

at Rutgers, Cliff wasnt there;

He didnt believe what he read

in the Spectator ‘Who’s that Jack’

So I come in on the St Benedicts game

not willing to be caught by them bums

I took off the kickoff right straight at

the gang, and lalooza’d around

To the pastafazoola five yard line,

you were there, you remember

We didnt make first down; and I

took the punt and broke my leg

And never said anything, and ate hot

fudge sundaes & steaks in the

Lion’s Den.

Because that’s one good thing that came of it, with my broken leg in a cast, and with two crutches under my good armpits, I hobbled every night to the Lion’s Den, the Columbia fireplace-and-mahogany type restaurant, sat right in front of the fire in the place of honor, watched the boys and girls dance, ordered every blessed night the same rare filet mignon, ate it at leisure with my crutches athwart the table, then two hot fudge sundaes for dessert, that whole blessed sweet autumn.

And I never did say anything, so as to say, I never sued or made a fuss, I enjoyed the leisure, the steaks, the ice cream, the honor, and for the first time in my life at Columbia began to study at my own behest complete awed wide-eyed world of Thomas Wolfe (not to mention the curricular work too).

For years afterward, however, Columbia still kept sending me the bill for the food I ate at training table.

I never paid it.

Why should I? My leg still hurts on damp days. Phooey.

Ivy League indeed.

If you dont say what you want, what’s the sense of writing?

IX

But O that beautiful autumn, sitting at my desk with that fragrant pipe now taped like my leg was taped, listening to the beautiful Sibelius Finnish Symphony which even to this day reminds me of fragrant old tobacco smoke and even tho I know it’s all about snow, and my dim lamp, and before me laid out the immortal words of Tom Wolfe talking about the ‘weathers’ of America, the pale-green flaky look of old buildings behind warehouses, the track running west, the sound of Indians in the rail, the coonskin cap in his hills of old Nawth Caliney, the river winking, the Mississippi, the Shenandoah, the Rio Grande . . . no need for me to try to imitate what he said, he just woke me up to America as a Poem instead of America as a place to struggle around and sweat in. Mainly this dark-eyed American poet made me want to prowl, and roam, and see the real America that was there and that ‘had never been uttered’. They say nowadays that only adolescents appreciate Thomas Wolfe but that’s easy to say after you’ve read him anyway because he’s the kind of writer whose prose poems you can just about only read once, and deeply and slowly, discovering, and having discovered, move away. His dramatic sections you can read over and over again. Where is the seminar on Tom Wolfe today? What is this minimization of Thomas Wolfe in his own time? Because Mr Schwartz could wait.

But there I am sitting at my desk, book open, and I says to myself: ‘Now it’s almost seven thirty, we’ll hobble down to ye olde Lion’s Den, have filet mignon, hot fudge sundaes, coffee, and then hobble on down to the one hundred sixteenth subway stop [remembering Prof Kerwick and his mathematics series numbers] and ride on down to Times Square and go see a Fre

nch movie, go see Jean Gabin press his lips together sayin “Ça me navre,” or Louis Jouvet’s baggy behind going up the stairs, or that bitter lemon smile of Michele Morgan in the seaside bedroom or Harry Bauer kneel as Handel praying for his work, or Raimu screaming at the mayor’s afternoon picnic, and then after that, an American doublefeature, maybe Joel McRae in Union Pacific, or see tearful clinging sweet Barbara Stanwyck grab him, or maybe go see Sherlock Holmes puffing on his pipe with long Cornish profile as Dr Watson puffs at a medical tome by the fireplace and Missus Cavendish or whatever her name was comes upstairs with cold roast beef and ale so that Sherlock can solve the latest manifestation of the malefaction of himself Dr Moriarty . . .’

Lights of the campus, lovers arm in arm, hurrying eager students in the flying leaves of late October, the library going with glow, all the books and pleasure and the big city of the world right at my broken feet . . .

And think of this in 1967: I even actually used to get on my crutches and go to Harlem to see what was going on, 125th Street and thereabouts, sometimes to watch spareribs turning in the spareribs shack window, or watch Negroes talk on corners; to me they were exotic people I’d never known before. I forgot to mention earlier, on my first week at HM in 1939, hands clasped behind my back I’d actually walked all over Harlem one whole warm afternoon and evening examining all this new world. Why didnt anybody hit up on me, say to sell me drugs, or hit me, or rob me: what did they see? They see a tweeded college boy studying the street. People have respect for those things. I must have been an awfully weird-looking character anyway.

So I’d go into the Lion’s Den, sit in my regular chair in front of the fire, the waiters (students) would bring me the supper, I’d eat, watch the dancers (one beauty in particular, Vicki Evans, interested me, Welsh girl), and then I’d go down to Times Square for my movies. Nobody ever bothered me. I always had, of course, nothing but something like sixty cents on me anyway and must have looked like it with that innocent face.

Tristessa

Tristessa On the Road

On the Road The Dharma Bums

The Dharma Bums Maggie Cassidy

Maggie Cassidy Big Sur

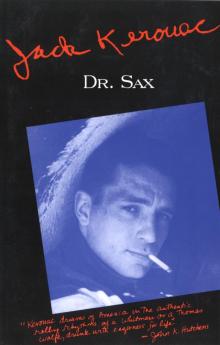

Big Sur Dr. Sax

Dr. Sax Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46

Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46 The Sea Is My Brother

The Sea Is My Brother The Town and the City: A Novel

The Town and the City: A Novel Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Desolation Angels: A Novel

Desolation Angels: A Novel Book of Sketches

Book of Sketches Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha

Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha The Electrocution of Block 38383939383

The Electrocution of Block 38383939383 Haunted Life

Haunted Life Visions of Gerard

Visions of Gerard Orpheus Emerged

Orpheus Emerged Book of Blues

Book of Blues The Subterraneans

The Subterraneans The Haunted Life

The Haunted Life The Unknown Kerouac

The Unknown Kerouac The Town and the City

The Town and the City Visions of Cody

Visions of Cody Atop an Underwood

Atop an Underwood Lonesome Traveler

Lonesome Traveler Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg Vanity of Duluoz

Vanity of Duluoz Desolation Angels

Desolation Angels On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition)

On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition) The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel

The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel Wake Up

Wake Up The Poetry of Jack Kerouac

The Poetry of Jack Kerouac Doctor Sax

Doctor Sax