- Home

- Jack Kerouac

Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46 Page 8

Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46 Read online

Page 8

Now also I had time to start writing big ‘Wolfean’ stories and journals in my room, to look at them today it’s a drag but at that time, I thought I was doing allright. I had a Negro student friend who came in and boned me on chemistry, my weakness. In French I had an A. In physics a B or C-plus or so. I hobbled around the campus proud like some skimaster. In my tweed coat, with crutches, I became so popular (also because of the football reputation now) that some guy from the Van Am Society actually started a campaign to have me elected vice-president of next year’s sophomore class. One thing sure I had no football to play till the sophomore year, 1941. To while away the time that winter I wrote sports a little for the college newspapers, covered the track coach interviews, wrote a few term papers for boys of Horace Mann who kept coming down to visit me. Hung around with Mike Hennessey as I say on that corner in front of the candy store on 115th and Broadway with William F. Buckley Jr sometimes. Hobbled down to the Hudson River and sat on Riverside Drive benches smoking a cigar and thinking about mist on rivers, occasionally took the subway to Brooklyn to see Grandma Ti Ma and Yvonne and Uncle Nick, went home for Christmas with the crutches gone and the leg practically healed.

Sentimentally getting drunk on port wine in front of my mother’s Christmas tree with G. J. and having to carry him home in the Gershom Avenue snow. Looking for Maggie Cassidy at the Commodore Ballroom, finding her, asking for a dance, falling in love again. Long talks with Pa in the eager kitchen.

Life is funny.

A cameo for size: one might in the Phi Gamma Delta fraternity house, where I was a ‘pledge’ but refused to wear the little blue skullcap, in fact told them to shove it and insisted instead on giving me the beer barrel which was almost empty, and raised it above my head at dawn and drained it of its dregs . . . all alone one night, in the completely empty frat house on 114th Street, except maybe for one or two guys sleeping upstairs, completely unlighted house, I’m sitting in an easy chair in the frat lounge playing Glenn Miller records fullblast. Almost crying. Glenn Miller and Frank Sinatra with Tommy Dorsey ‘The One I Love Belongs to Somebody Else’ and ‘Everything Happens to Me’, or Charlie Barnet’s ‘Cherokee’. ‘This Love of Mine’. Helping paralytic or spastic Dr Philippe Claire across the campus, we’ve just been working on his crossword puzzles which he writes for the New York Journal-American, he loves me because I’m French. Old Joe Hatter coming into my dormitory room one drenching night with battered hat all dissolved in rain, bleary-eyed, saying, ‘Jesus Christ is pissing on the earth tonight.’ At the West End bar Johnny the Bartender looking over everybody’s heads with his big hands on the counter. In the lending library I’m studying Jan Valtin’s Out of the Night, still a good book today to read. I wander around the Low Library wondering about libraries, or something. Told you life was funny. Girls with galoshes in the snow. Barnard girls growing bursty like ripe cherries in April, who the hell can study French books? A tall queer approaching me on the Riverside Park bench saying ‘How you hung?’ and me saying ‘By the neck, I hope.’ Turk Tadzic, varsity end of next year, crying drunk in my room telling me how he once squatted on Main Street in a Pennsy town and shat in front of everybody, ashamed. Guys pissing outside the West End bar right on the sidewalk. The ‘lounge lizards’, guys who sit in the dormitory lounge doing nothing with their legs up on other chairs. Big notes pinned to a board saying where you can buy a shirt, trade a radio, get a ride to Arkansas, or go drop dead more or les. My leg’s better, I’m now a waiter in John Jay dining hall, that is, I’m the coffee waiter, with coffee tray balanced in left hand I go about, inquisitively, gentlemen and ladies give me the nod, I go to their left and pour delicate coffee in their cups; a guy says to me: ‘You know that old geezer you just poured coffee for? Thomas Mann.’ My legs better, I saunter over Brooklyn Bridge remembering that raging blizzard in 1936 when I was fourteen years old and Ma’d brought me to Brooklyn to visit Grandma Ti Ma: I had my Lowell overshoes with me: I’d said ‘I’m going out and walk over the Brooklyn Bridge and back,’ ‘Okay,’ I go over the bridge in a howling wind with biting sleet snow in my red face, naturally not a soul in sight, except here comes this man about 6 foot 6, with large body and small head, striding Brooklyn-ward and not looking at me, long strides and meditation. Know who that old geezer was?

Thomas Wolfe.

Go to Book Five.

Book Five

I

Late that spring, just about when my freshman year was over and the sophomore year was on the way, I was coming out of a subway turnstile with Pa after we’d seen a French movie on Times Square and here comes Chad Stone the other way, with a bunch of Columbia footballers. Chad was destined to become captain of the Columbia varsity, later a doctor, later to die at age thirty-eight of an overworked heart, goodlooking big fellow from Leominster Mass. by the way, and he says to me: ‘Well, Jack, you’ve been elected vice-president of the sophomore class.’

‘What? Me?’

‘By one vote, you rat, by one vote over ME.’ And it was true. My father immediately took my picture in a ratty Times Square booth but little did he dream what was about to happen to my dingblasted old sophomore year, it was now May 1941 and events were brewing indeed in the world. But this sophomore vice-president boloney had no effect on my chemistry professor, Dr So-and-So, who, puffing on his pipe, informed me that I had failed chemistry and had to make it up that summer at home in Lowell or lose my scholarship.

Thing about chemistry was, the first day I’d gone to class, or lab, that fall of 1940, and saw all those goddamned tubes and stinking pipes and saw these maniacs in aprons fiddling around with sulfur and molasses, I said to myself ‘Ugh, I’m never going to attend this class again.’ Dont know why, couldnt stand it. Funny too, because in my later years as more or less of a ‘drug’ expert I sure did get to know a lot about chemistry and the chemical balances necessary for certain advantageous elations of the mind. But no, an F in chemistry, first time I’d ever flunked a course in my life and the professor was serious. I wasnt about to plead with him. He told me where to get the necessary books and tubes and Faustian whatnots to take home for the summer.

It was a nutty summer at home, therefore, where I absolutely refused to study my chemistry. I missed my Negro friend Joey James who’d tried to bone me all year, as I say.

I went home that summer, and instead I played around with swimming, drinking beer, making huge hamburger sandwiches for me and Lousy (‘Ye old Zaggo Special’ he called them because they were nothing but hamburg fried in lots of real butter and put on fresh bread with ketchup), and when late August came around I still hadnt made anything up in particular. But by now they were ready to let me try the course over again, as according to Lu Libble’s plan, and other friends, because now we had a football team to contend upon and anyway I was probably smart enough to make it all up. Oddly, I didnt want to.

That summer Sabbas became a regular in my old boyhood gang of G. J., Lousy, Scrotcho et al. and we even took a crazy trip to Vermont in an old jalopy to get drunk on whiskey for the first time in the woods, at a granite quarry swimming hole. At this swimming hole I took a deep breath, drunk, and went way down about 20 feet and stayed there grinning in the goggly dark. Poor Sabbas thought I had drowned, whipped off all his clothes and dove in after me. I popped up laughing. He cried on the bank. (St Sabbas was the founder of a sixth-century monastery, Greek Orthodox, now buried in Holy Sepulcher Church in Jerusalem under the officiation of Patriarch Benedictos in 1965.) I took another shot of whiskey and grabbed a little tree about 5 feet tall, wrapped it around my bare back, and tried to rip it up by the roots from the earth. G. J. says he’ll never forget it: he says I tried to pull all Vermont up from the roots. From then on he called me ‘Power Mad’. As we drank the whiskey further I saw the Green Mountains move, to paraphrase Hemingway in his sleeping sack. We drove back to Lowell drunk and sick, me sleeping on Sabby’s lap all the way, as he cried, then dozed, all night.

Also, I hitchhiked to Boston a couple of times with Dicky Hampshire to prowl the waterfront to see if we could hop a ship for Hong Kong and become big Victor McLaglen adventurers. On Fourth of July we all went to Boston and wandered around Scollay Square looking for quiff that wasnt there. I spend most of my Friday nights singing every show tune in the books under an apple tree in Centreville, Lowell, with Moe Cole: and boy could we sing: and later she sang with Benny Goodman’s band awhile. She once came to see me in broad afternoon summer wearing a tightfitting fire engine red dress and high heels, whee. (I’m not mentioning love affairs much in this book because I think acquiescing to the lovin whims of girls was the least of my Vanity.)

But the summer wore on and I never got my chemistry figured out and then came the time when my father, who’d been working out of town as a linotypist, sometimes at Andover Mass., and sometimes Boston, sometimes Meriden Conn., now had a steady job lined up at New Haven Conn. and it was decided we move there. My sister by now was married. As we were packing, I went about and nighted the Pawtucketville stars of trees and wrote sad songs about ‘picking up my stakes and rolling’. But that wasnt the point.

One night my cousin Blanche came to the house and sat in the kitchen talking to Ma among the packing boxes. I sat on the porch outside and leaned way back with feet on rail and gazed at the stars, the Milky Way, the whole works clear. I stared and stared till they stared back at me. Where the hell was I and what was all this?

I went into the parlor and sat down in my father’s old deep easy chair and fell into the wildest daydream of my life. This is important and this is the key to the story, wifey dear:

As Ma and Cousin talked in the kitchen, I daydreamed that I was now going to go back to Columbia for my sophomore year, with home in New Haven, maybe near Yale campus, with soft light in my room and rain on the sill, mist on the pane, and go all the way in football and studies. I was going to be such a sensational runner that we’d win every game, against Dartmouth, Yale, Princeton, Harvard, Georgia U, Michigan U, Cornell, the bloody lot, and wind up in the Rose Bowl. In the Rose Bowl, worse even than Cliff Montgomery, I was going to run wild. Uncle Lu Libble for the first time in his life would throw his arms around me and weep. Even his wife would do so. The boys on the team would raise me up in Rose Bowl’s Pasadena Stadium and march me to the showers singing. On returning to Columbia campus in January, having passed chemistry with an A, I would then idly turn my attention to winter indoor track and decide on the mile and run it in under 4 flat (that was fast in those days). So fast, indeed, that I’d be in the big meets at Madison Square garden and beat the current great milers in final fantastic sprints bringing my time down to 3:50 flat. By this time everybody in the world is crying Duluoz! Duluoz! But, unsatisfied, I idly go out in the spring for the Columbia baseball team and bat homeruns clear over the Harlem River, one or two a game, including fast breaks from the bag to steal from first to second, from second to third, and finally, in the climactic game, from third to home, zip, slide, dust, boom. Now the New York Yankees are after me. They want me to be their next Joe DiMaggio. I idly turn that down because I want Columbia to go to the Rose Bowl again in 1943. (Hah!) But then I also, in mad midnight musings over a Faustian skull, after drawing circles in the earth, talking to God in the tower of the Gothic high steeple of Riverside Church, meeting Jesus on the Brooklyn Bridge, getting Sabby a part on Broadway as Hamlet (playing King Lear myself across the street) I become the greatest writer that ever lived and write a book so golden and so purchased with magic that everybody smacks their brows on Madison Avenue. Even Professor Claire is chasing after me on his crutches on the Columbia campus. Mike Hennessey, his father’s hand in hand, comes screaming up the dorm steps to find me. All the kids of HM are singing in the field. Bravo, bravo, author, they’re yelling for me in the theater where I’ve also presented my newest idle work, a play rivaling Eugene O’Neill and Maxwell Anderson and making Strindberg spin. Finally, a delegation of cigar-chewing guys come and get me and want to know if I want to train for the world’s heavyweight boxing championship fight with Joe Louis. Okay, I train idly in the Catskills, come down on a June night, face big tall Joe as the referee gives us instructions, and then when the bell rings I rush out real fast and just pepper him real fast and so hard that he actually goes back bouncing over the ropes and into the third row and lays there knocked out.

I’m the world’s heavyweight boxing champion, the greatest writer, the world’s champ miler, Rose Bowl and (pro-bound with New York Giants football non pareil) now offered every job on every paper in New York, and what else? Tennis anyone?

I woke up from this daydream suddenly realizing that all I had to do was go back on the porch and look at the stars again, which I did, and still they just stared at me blankly.

In other words I suddenly realized that all my ambitions, no matter how they came out, and of course as you can see from the preceding narrative, they just came out fairly ordinary, it wouldnt matter anyway in the intervening space between human breathings and the ‘sigh of the happy stars’, so to speak, to quote Thoreau again.

It just didnt matter what I did, anytime, anywhere, with anyone; life is funny like I said.

I suddenly realized we were all crazy and had nothing to work for except the next meal and the next good sleep.

O God in the Heavens, what a fumbling, hand-hanging, goof world it is, that people actually think they can gain anything from either this, or that, or thissa and thatta, and in so doing, corrupt their sacred graves in the name of sacred-grave corruption.

Chemistry shemistry . . . football, shmootball . . . the war must have been getting in my bones.

When I looked up from that crazy reverie, at the stars, heard my mother and cousin still yakking in the kitchen about tea leaves, heard in fact my father yelling across the street in the bowling alley, I realized either I was crazy or the world was crazy; and I picked on the world.

And of course I was right.

II

In any case my father had gone ahead to New Haven, started working on the job in West Haven it was, and idly, or let someone else do it, had an ‘apartment’ found for us in the Negro Ghetto district of New Haven. It wasnt so much that my mother or father or myself minded Negroes, God bless em, but broken glass and crap on the floor, broken windows, bottles, ruined plaster, the works. Ma and I traveled from Lowell, following the moving truck, on the New Haven Railroad, got there at dawn, a musty fust of pluck mist over the railyards at sunrise, and we walk in the hotting streets to this third story crapulous ‘apartment’, ‘Is that man crazy?’ says Ma. Already, after having done all the packing and arrangements, and after even running downstairs after poor Ti Gris our cat and falling down the stairs after it (on Gershom Avenue) and hurting her hip and leg, here she is, hopefully perfumed, tho worn out from the all-night train from Lowell with its interminable silly stops in Worcester or someplace of all p

laces, here she finds a place not even the cheapest landlord on Lowell or Tashkent would rent to the milkiest Kurd or horsiest Khan in Outer Twangolia, let alone French Canadians used to polished-floor tenements and Christmas cheer based on elbow grease and Hope.

So we call up Pa, he says he didnt know any better, he says he’ll call a French Canadian realtor and mover of New Haven and see what we can find. Ends up, Fromage the French Canadian mover has a little cottage by the sea at West Haven not far from Savin Rock Park. Our furniture by now is in the warehouse in New Haven. My little kitty Ti Gris has jumped out of his box somewhere along the route when the truckers stopped for chow and is gone forever in the woods of New England. In the warehouse as they’re shoving around I see one of Ma’s dresser drawers yaw open and inside I see her bloomers, crucifixes, rosaries, rubber bands, toys; it suddenly occurs to me people are lost when they leave their homes and convey themselves to the hands of brigands good or bad as they may be. But the French Canadian man, old fellow about sixty, has that wonderful French Canadian accent on Hope and says ‘Come on, cheer up, là bas [“there”] let’s get the stuff on the truck, rain or no rain’ – it’s raining cats and dogs – ‘and let’s go to your new cottage by the sea. I’ll rent it to you for sixty dollars a month, is that so bad? We even buy a bottle to nip us along and all go on the truck, the man, then Pa, then me all huddled up against the door, and Ma between Pa and me. Off we go in the rain. We drive out to the seacoast of Long Island Sound and there’s the cottage.

They park the truck, the other French Canadian movers show up, and boom, they’re unloading everything and rushing into the cottage with it. It’s a two-story affair with three bedrooms upstairs, kitchen, parlor, heating arrangement, what else do you want? In the glee of the situation, and a little high on the bottle, I put on my swim trunks and ran across the mud toward the strand in a lashing gale from the Sound. Ah that menace of monstrous rolling waves of gray water and spray, put me in the mind of something past and something future.

Tristessa

Tristessa On the Road

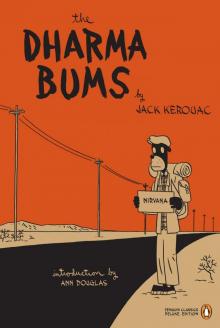

On the Road The Dharma Bums

The Dharma Bums Maggie Cassidy

Maggie Cassidy Big Sur

Big Sur Dr. Sax

Dr. Sax Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46

Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935-46 The Sea Is My Brother

The Sea Is My Brother The Town and the City: A Novel

The Town and the City: A Novel Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings

Atop an Underwood: Early Stories and Other Writings Desolation Angels: A Novel

Desolation Angels: A Novel Book of Sketches

Book of Sketches Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha

Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha The Electrocution of Block 38383939383

The Electrocution of Block 38383939383 Haunted Life

Haunted Life Visions of Gerard

Visions of Gerard Orpheus Emerged

Orpheus Emerged Book of Blues

Book of Blues The Subterraneans

The Subterraneans The Haunted Life

The Haunted Life The Unknown Kerouac

The Unknown Kerouac The Town and the City

The Town and the City Visions of Cody

Visions of Cody Atop an Underwood

Atop an Underwood Lonesome Traveler

Lonesome Traveler Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg Vanity of Duluoz

Vanity of Duluoz Desolation Angels

Desolation Angels On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition)

On the Road: The Original Scroll: (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition) The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel

The Sea Is My Brother: The Lost Novel Wake Up

Wake Up The Poetry of Jack Kerouac

The Poetry of Jack Kerouac Doctor Sax

Doctor Sax